We have a confession: When Taylor’s new Gold Label Collection was unveiled earlier this year, we only hinted at one of the most innovative, player-centric features of the guitars. It’s a patented new neck joint from chief designer Andy Powers called the Action Control Neck™.

There were two reasons we let this fly under the radar. For starters, the design doesn’t call attention to itself — the magic is entirely hidden in the internal structure of the neck joint and the body’s neck pocket. Second, the headline story with the Gold Label guitars was their unique sound — a warmer, vintage-inspired tonal personality that’s dramatically different from anything Taylor has made before. We didn’t want to divert attention from that, though we did talk about one specific aspect of the new neck design — a proprietary long-tenon neck joint — because it was in the context of how the design helped shaped the tone profile.

But we’re happy to talk about the neck’s virtues now. In fact, we view it as another significant step forward for Taylor in our obsessive drive to improve the playability and, crucially in the case of the Action Control Neck, the adjustability, of acoustic guitars.

Why Playability Matters

A guitar’s playability can shape our entire relationship with the instrument. A smooth, responsive neck can be the spark that transforms a hesitant beginner into a lifelong player. It can remove barriers to creativity, allowing melodies to flow effortlessly from our fingertips. For seasoned musicians, it’s the difference between struggling through a set and feeling fully connected to the music. And as the years go by, playability ensures we can continue playing with ease, even when our hands don’t move as quickly as they once did. A guitar with a playable neck becomes more than an instrument — it resonates as an extension of ourselves.

Tracing Our Heritage of Playability Innovation

Before unpacking the details of Andy’s new neck design, we thought we’d zoom out for some historical context and recount how playability became a pillar of the Taylor experience. Specifically, we want to spotlight two of the most consequential innovations in Taylor neck design, which set the stage for Andy: first, the birth of Bob’s original slim-profile, easy-playing necks, which put Taylor on the map in the mid-’70s. Second, Bob’s radical redesign of the Taylor neck in 1999, which brought unprecedented neck angle precision and micro-adjustability to our guitars. Both were bona fide game-changers when it came to improving playability and serviceability. Lastly, Andy’s next-generation Action Control Neck picks up where Bob left off and delivers what we believe is yet another important advance in Taylor playability.

If you’d rather skip ahead and read about Andy’s Action Control Neck, click here.

I. Skinny, Removeable Necks

“When we made our first guitar in 1974, we made it with a slim, fast neck shape. Players and store owners were flabbergasted that we could make a neck so thin and comfortable.”

— Bob Taylor

Fifty years ago, playability was not a trait associated with steel-string acoustic guitars. Most of the prominent acoustic guitars of the day had bigger, rounder necks to make them more stable and less prone to warping or twisting. The downside was that this made them harder to play, especially for players inclined to venture past the first few frets.

You might say a young Bob Taylor stumbled his way into making a more playable acoustic guitar neck through a serendipitous blend of ignorance and pragmatic, problem-solving resolve.

If You Can’t Buy It, Build It

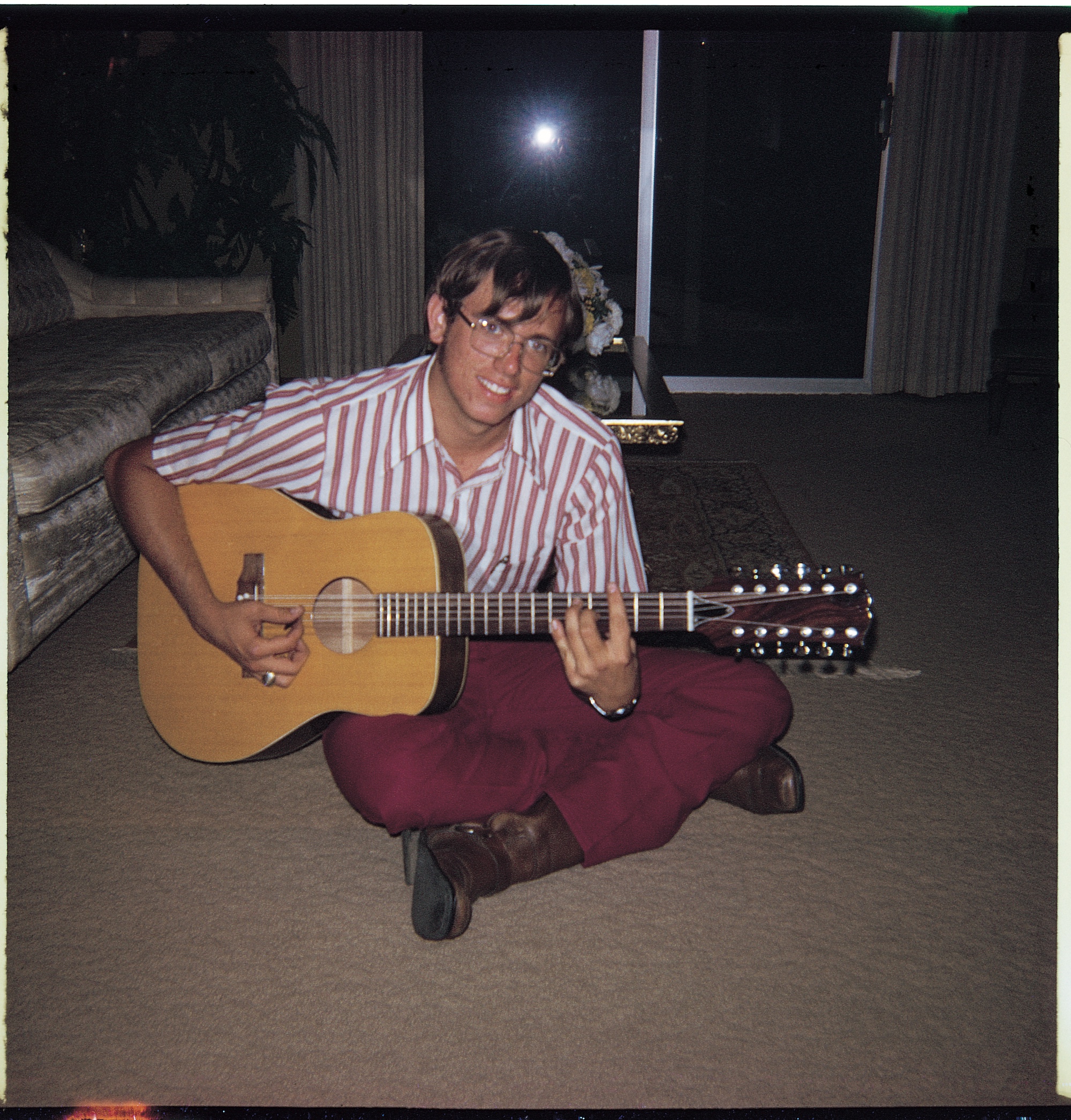

As a teenager, Bob discovered an acoustic 12-string EKO Ranger in a local music store. It had a skinny, bolt-on neck (similar to what Fender used for its electric guitars) and low action. Bob didn’t have the money to buy it, so he decided to make his own 12-string in his eleventh-grade woodshop class.

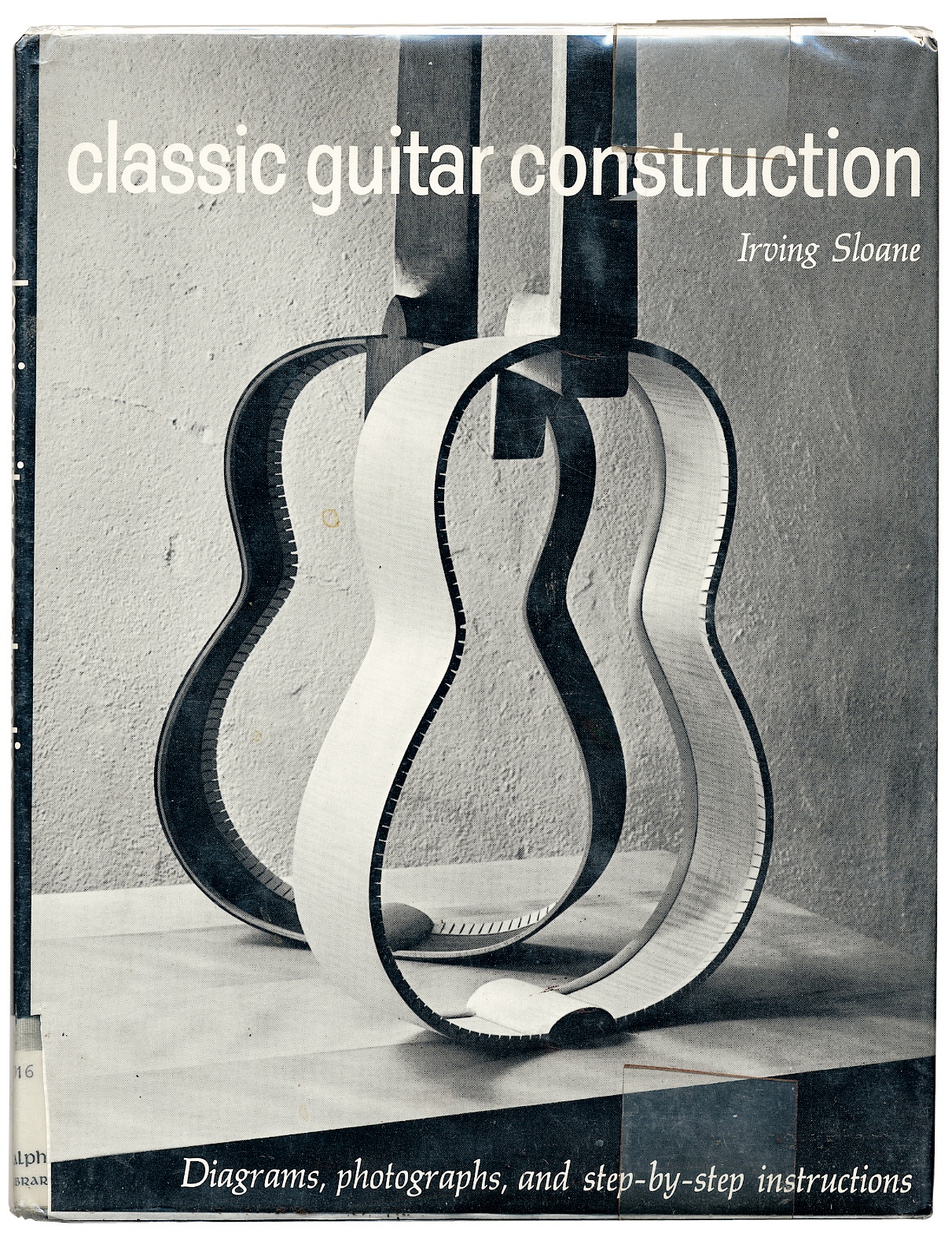

Bob’s woodshop teacher offered some basic guidance and lent him the Irving Sloane book “Classic Guitar Construction” — one of the few written resources available to the public at the time. Bob built his guitar over the course of the school year, and in the process, sparked a passion that became his career path.

Be Original

After graduating, Bob started working at the American Dream, a local guitar-making co-op in San Diego, where he learned he had a lot to learn. Co-owner and luthier Sam Radding turned out to be a seminal influence in terms of shaping Bob’s philosophy of building.

“Sam made his own guitars,” Bob says. “He had his own shapes, his own ideas, his own way to make a neck joint. He was original. That was an important early lesson for me, and something that became important to the success of Taylor Guitars.”

Keeping a Low Profile

Bob’s earliest guitars at the Dream stood out right away for their slim-profile necks. He wasn’t familiar enough with the guitars of other brands to know how thick a neck was “supposed” to be.

“I probably had that EKO Ranger in my mind, so I just shaved the neck until it started to feel right,” Bob says. “Other people at the Dream would walk by [and feel the neck] and go, ‘Wow, this neck is skinny. Why are you making it so skinny?’ and I’d go, ‘I don’t know, it feels good to me.’ The next thing you know, word got out that I made skinny necks with low action.’”

In this segment from Episode 1 of the podcast American Dreamers: 50 Years of Taylor Guitars, Bob Taylor talks about the origin of his slim-profile necks.

Taylor co-founder Kurt Listug, who was also working at the Dream at that time, remembers that the new acoustic guitars of the day were not especially hand friendly.

“They were incredibly hard to play,” he says. “People would bring their guitars by the shop to have the necks reshaped.”

A Joint Venture

Throughout much of the 20th century, steel-string acoustic guitar necks had been attached to guitar bodies with a traditional dovetail joint or some version of a mortise-and-tenon joint. While revered for its craftsmanship, the dovetail presented challenges — primarily that once set, the neck angle was difficult to adjust, and resetting it required extensive work by a skilled luthier.

Bob remembers making his first version of a bolt-on acoustic neck while at the Dream. It actually was a repair job, which turned out to be an improvised conversion from a dovetail to a bolt-on joint for a friend’s Guild G-37. The repair required Bob to remove the neck, but after realizing it would be difficult and time-consuming to work with a dovetail, he opted for a more industrial, problem-solving approach. He cut off the dovetail, glued the block back into the body, drilled holes, and converted it to a bolt-on neck. In the end, the guitar played great, and his friend didn’t mind the major structural alteration because of the improved playability.

While at the Dream, Bob was exposed to a variety of neck joints as he refined his craft. Sam Radding taught him to make what he called a “T-Block” neck joint with a mortise and tenon holding it. Bob moved to a bolt-on mortise-and-tenon version, then a butt joint (influenced by luthier David Russell Young), and eventually a bolt-on design. Both Radding and another luthier at the Dream, Greg Deering (who would go on to found the Deering Banjo Company) had built versions of guitars with bolt-on necks, and Bob continued to filter the different ideas floating around the shop to create his own version. One fellow San Diego luthier who helped was Bob’s friend Jim Goodall, who developed a threaded insert that Bob started using to secure his necks to the body.

By the time Bob and Kurt partnered to buy the American Dream from Radding and became Taylor Guitars, Bob had developed his own version of a bolt-on neck assembly for his guitars.

Convincing the Skeptics

While Bob’s slim-profile, low-action necks were attracting players, some traditionalists weren’t so receptive. For starters, they predicted the lack of girth in the neck profile would make the necks more prone to twisting and warping. Also, the dovetail joint had a venerable heritage in the steel-string acoustic guitar world. Critics of the bolt-on approach claimed it was used primarily because it was cheaper, that it wasn’t as strong a joint as a dovetail (especially in Bob’s case, because his necks were slimmer), and that the dovetail produced superior tonal transfer between the body and neck.

“Our customers for the first several years were largely electric guitar players who had virtually given up on ever playing an acoustic.”

Bob Taylor

It didn’t help that a couple of other existing versions of a bolt-on acoustic neck design out in the world, like the Fender Palomino, were known to be problematic. Even the term “bolt-on” suggested a less refined approach. That’s one reason why Bob often made a point of referring to the necks as “removable,” which spoke to the advantage they offered when it came to adjusting them to maintain their low action and playability over time. Utility and serviceability would prove to be guiding themes as Bob continued to refine his processes over the years.

Ultimately, despite the naysaying, Bob’s necks stayed straight and held up just fine.

As for the claim that the bolt-on approach wasn’t as strong as a glued dovetail joint, Bob addressed this in a 1996 article in Wood&Steel.

“The same type of joint we used for a neck is what they use to put the cylinder head on a car,” he pointed out. “They mill two surfaces perfectly flat, bolt them together, and it’s strong enough to contain 180 pounds-per-square-inch of compression.”

Bob also contested the assertion that his bolt-on approach was an inferior vehicle for the transfer of sound.

“Our neck has easy, no-stress, complete contact with the body,” he said. “The body and neck have beautifully lapped, mated surfaces, and the joint doesn’t have to be pounded with a hammer to wedge it in. When a dovetail is hammered into place, it has shims and glue and air space. Our joint fits snugly around the edge, and we torque the bolts until it makes perfect contact.”

Bob’s 10,000 Hours of Setting Neck Angles

In retrospect, Bob regards his removable, bolt-on neck design as an “unplanned asset” that gave him a working platform to master the art of setting a neck angle for ideal playability and performance in Taylor’s early years. As he described it, those were the grassroots days of direct builder-to-customer accountability, when they’d sell a guitar directly to a customer and, in Bob’s words, “immediately become an indentured servant to the guy who bought it” to ensure that it played as easily as possible. This forced Bob to level up his setup chops on the fly. It also helped him appreciate the importance of serviceability as a design consideration.

“At the time, the bigger, more successful makers could counter a complaint [about playability] by saying a guitar was ‘within factory specs,’ which was another way of saying, ‘Sorry, that’s as good as your guitar is going to play,’” Bob said in Wood&Steel. “I couldn’t say my guitar was within specs because I didn’t have any specs back then. And the customer was right there in the shop. But with the removable neck, I could take a neck off and put it back on over and over if I had to until I made the guitar right and sent the owner home happy. So we spent a lot of time learning how to make the slightest adjustments. Over time, we developed a vast pool of knowledge about neck angles and sweet spots and could incorporate that knowledge into our designs moving forward. In the end, we pioneered this whole new world of ‘low-profile’ necks.”

II. A New Neck for a New Millennium

“I’m looking at a CNC machine thinking, we’ve just been mimicking hand motions. Why don’t I use it to do things that can’t be done by hand?”

— Bob Taylor

Another breakthrough was the 1999 debut of Bob’s patented new neck joint, referred to at the time as the “NT” neck. (“NT” stood for “New Technology.”) The neck was first featured on a series of limited-edition guitars celebrating Taylor’s milestone 25th anniversary before migrating to the rest of the line over the course of the following year.

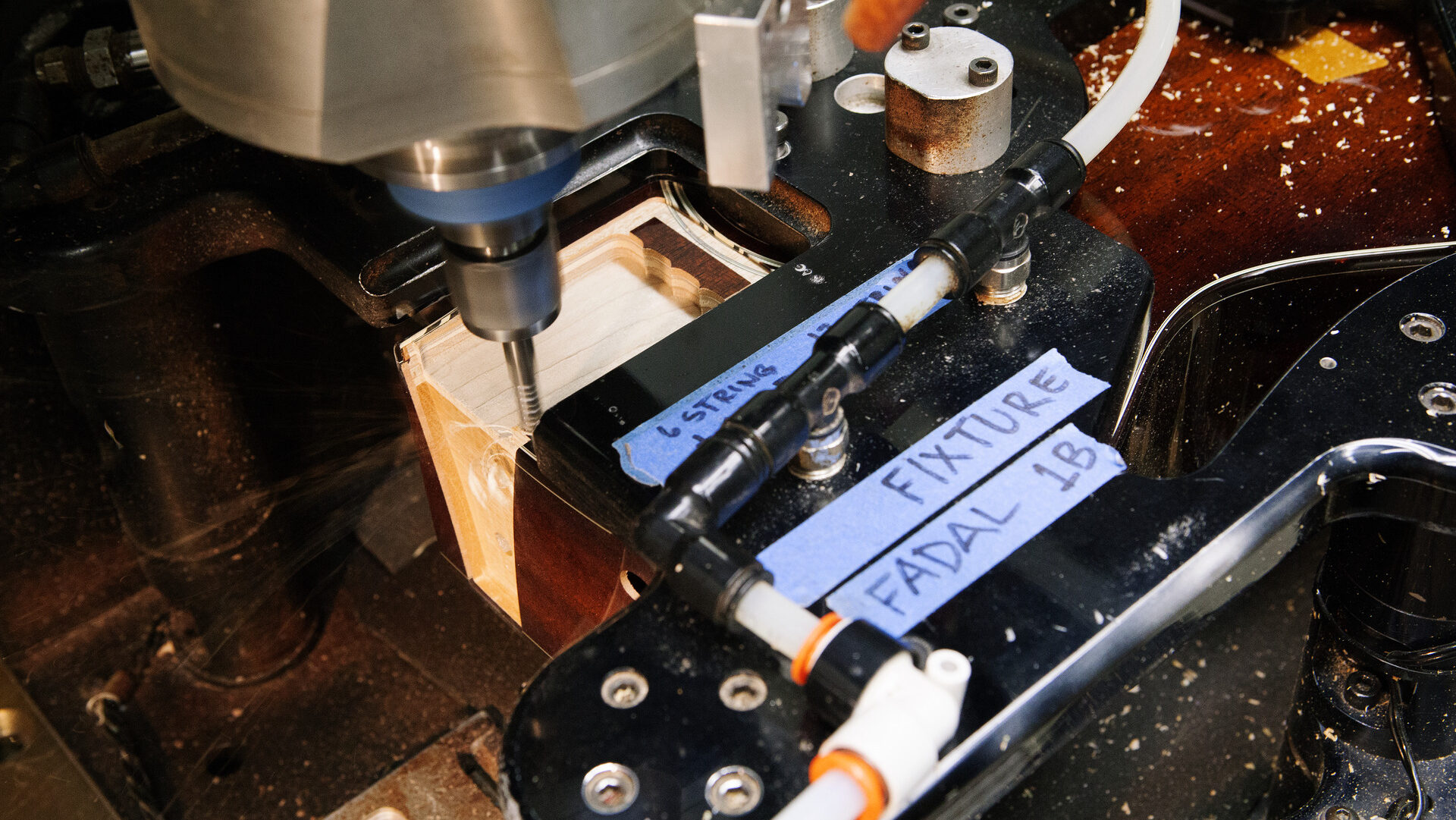

In many ways, the revolutionary neck design seemed a fitting culmination of a decade that had brought prolific innovation and growth at Taylor. Bob had purchased his first CNC (computer numerical control) mill at the end of 1989. (He was the first acoustic builder to do this, though he’s always quick to credit electric builder Tom Anderson, a fellow SoCal guy, for introducing him to them.)

In this clip from the Episode 5, Part 1 of the podcast American Dreamers: 50 Years of Taylor Guitars, Bob Taylor and Kurt Listug talk about harnessing computer milling technology to produce the NT neck, the importance of preserving the traditional visual aesthetic of an acoustic guitar, and why making a more consistent guitar body was essential to the neck design.

The capabilities of CNC technology proved to be a remarkable catalyst for unprecedented refinements to the guitar-making process at Taylor throughout the ’90s. It brought unprecedented precision and consistency to guitar making and created an exciting new platform for tooling and manufacturing innovation, which Bob heartily embraced.

With CNC technology at his disposal, Bob was no longer limited to replicating the traditional processes of hand-building movements and tools; he could pursue entirely new methodologies and better control the all-important geometry of a guitar’s construction.

Bob’s new neck design addressed a lingering structural limitation that Taylor’s existing necks shared with traditional dovetail neck designs. In both cases, when the neck was attached to the body, the cantilevered fretboard extension remained unsupported. As a result, it was glued to the guitar top to secure it. This problematic relationship was unique to a steel-string flattop acoustic — it’s the only acoustic stringed instrument in which the uppermost part of the fretboard traditionally extends independently beyond the end of the neck and is glued directly to the body.

As we noted in our Wood&Steel cover story on the “NT” neck (“Guitars for a New Millennium,” winter 1999), by contrast, on archtop guitars, violins, cellos, etc., the fingerboard and neck are one paired unit all the way up to the end. The neck attaches to the body in only one place, at the heel, leaving the rest of the neck/fingerboard extension to float above the guitar body. If the body swells, it doesn’t lift the neck/fingerboard with it. That’s why you hear about flattop guitars needing neck resets, but not archtops or violins or cellos.

Bob’s new neck design added stability to the neck in that fretboard extension area by supporting the fretboard nearly the entire way and by changing the way the neck meets the body. The extra fretboard support comes from the neck’s “paddle” joint — a CNC-milled, 3/8-inch-thick extension of the neck beyond the heel. A CNC mill also is used to rout pockets into the body to receive the heel, neck joint and fretboard. As a result, the neck can be inset into the body independently of the top, which means it won’t rise or sink if the top moves from changes in humidity.

To ensure that every neck angle is set with the correct geometry for optimal performance, a pair of laser-cut shims, tapered in varying increments of two-thousandths of an inch (about half the thickness of a sheet of loose-leaf paper) are placed into the pockets in the body prior to securing the neck (determined by a precise measurement from a digital neck angle gauge), allowing for precise micro-calibration of the neck angle on every guitar. Our ability to easily set every Taylor neck with that degree of accuracy means everything is optimized for intonation and playability. The way the neck joint meets the body — a solid connection of wood surfaces without glue — enables an efficient transfer of tone between the body and the neck.

“We can make hundreds of guitars a day with complete precision and consistency in each neck. And we can do it throughout the entire line, from the Baby through the Presentation Series.”

Bob Taylor

Twenty-five years since its debut, we continue to use this neck/body assembly. (Nowadays we simply call it the Taylor neck.) It’s made our guitar neck angle easier to set in Final Assembly at the Taylor factory and easier to adjust for a Taylor-certified guitar technician throughout the life of the guitar. It’s simply a matter of unbolting the neck, which features a glueless, three-bolt internal assembly (the three bolts are accessible through the soundhole) and then swapping out the neck angle shims for a pairing with a different value to recalibrate the angle. A trained technician can do this in about 15 minutes, and the work never compromises the structural integrity of the guitar.

III. The Action Control Neck

“With this neck design, you’re getting the most precisely built, easily adjustable guitar we’ve ever made.”

— Andy Powers

Many acoustic guitar owners don’t realize that over time, the angle between the guitar’s neck and body will naturally shift. This isn’t a design defect; it’s just the nature of wood. At some point, a small neck adjustment will be needed to restore the guitar’s playability and tone.

Taylor Service Network Manager Rob Magargal, an expert repair technician who has worked on thousands of guitars in various regions of the world over his 34 years with the company, understands this well.

“Even the best-made acoustic guitars will most likely need a neck angle adjustment, possibly two, within their life span,” Rob says. “This has to do more with environmental issues such as the humidity levels where the instrument lives. Guitars are made of organic materials. It’s the natural settling of the wood and the way it acclimates to its conditions. Also, guitars are always under string tension. All these factors will affect the instrument’s neck angle over time.”

If you’ve had your acoustic guitar for a while and haven’t had the neck angle checked or adjusted by a certified Taylor service technician, it might be worth looking into — especially if it’s not playing or sounding quite right. Even if you haven’t noticed anything, the change can be so gradual that you don’t realize it until after an adjustment, much like getting your car’s wheels realigned and suddenly feeling the smoother handling.

A playable guitar neck will roll out the red carpet to welcome a beginner. It will fast-track one’s growth as a player. It will reliably coax the best from a pro.

Rob has seen the positive reactions from players after servicing their guitars and resetting the neck angle — sometimes in real time at in-store Taylor re-string events.

“It’s fun to watch people react when they have a chance to play it again,” he says. “The response is often something like, ‘Wow, this feels like a whole new guitar.’”

Andy’s New Long-Tenon Neck Joint

When Andy Powers first began working on the design of what would become the Gold Label guitars a few years ago, he spent a lot of time thinking about the neck joint for good reason: he knew the design could impact both the sound and playability.

He knew he wanted these guitars to produce a sound that was warmer, fuller and deeper than the modern, high-fidelity sound long associated with Taylor guitars.

“We want to offer players a broad range of tonal flavors to choose from,” Andy says.

He also knew that the way the neck and body were coupled would contribute to the tonal character. That led to his design of a long-tenon neck joint.

The design bears similarities to Bob’s “NT” design: The fretboard extension is similarly supported by a paddle joint that extends beyond the heel; the body features a dual-pocketed neck block where the neck will be inset and secured; and the assembly is glueless.

One key difference is the namesake long tenon, which protrudes beyond the heel and extends deeper into the guitar body’s neck block (which is precision-routed to accommodate the tenon). Together with the heel structure, this changes the wood coupling in a way that’s comparable to the coupling of traditional guitar necks. The tenon increases the stiffness of the heel, which translates into more low-end resonance and a deeper, warmer, more open sound.

Instant Action Control

The other important design difference is that tapered shims are no longer needed to set the neck angle. Instead, the neck angle and string height can be adjusted after the neck is bolted in place simply by using a quarter-inch nut driver (or standard truss rod wrench) on a nut in the neck block, accessible through the soundhole. This ease of neck angle adjustability is a huge innovation because of how it simplifies the process, as Andy explains.

“As the adjustment bolt is tightened, the heel rocks backward minutely, tilting the neck away from the top of the guitar and pulling the strings closer to the fretboard,” he says. “Because this adjustment can be made while the guitar is tuned up to pitch, it completely eliminates the trial-and-error adjustment method of setting a neck angle with the strings off and hoping the guitar body responds to the strain of the strings the way you hoped.”

With the Action Control Neck, players (or a trained store salesperson or a service technician) now can adjust the guitar’s string height on their own to suit their exact preference if they choose. Neither the strings nor the neck needs to be removed to do this (remember, no neck angle shims are needed), and if you have a quarter-inch nut driver with a flexible extension shaft, you can access the adjustment bolt without even having to slack the strings. (To make it even easier to make the adjustment, you can also pick up a quarter-inch bit holder like this one.)

How to Adjust the String Height

In this video, Rob Magargal explains how to adjust the neck angle on a Gold Label guitar with an Action Control Neck.

Once the guitar’s humidification level is in a healthy range, it’s essentially a three-step process:

- Tune the guitar to whatever tuning you normally play in.

- Make sure the neck relief is correct. If necessary, make a truss rod adjustment.

- Adjust the string height with a micro-turn of the bolt head in the neck block using a ¼-inch nut driver. (Turning clockwise/right lowers the string action; turning counterclockwise/left raises it.)

Neither the neck nor the strings need to be removed to adjust the action. If you have a flexible extension shaft/flex arm tool, you can reach the bolt head without even slacking the strings. You can also use a truss rod wrench; you’ll just need to slack the D and G strings to reach inside the soundhole to access the bolt.

What Action Control Means for Players

That ease of adjustability will be music to the ears of discerning players who play different styles of music and want to tweak their action on the fly to accommodate this.

“This will be amazing for pro players,” says Rob Magargal. “Being able to change the guitar from a loud boomer to a soft fingerstyle guitar on the fly in a studio environment is huge. They can adjust to higher action for slide guitar and then to low action for leads.”

UK-based singer-songwriter Danny Worsnop (former lead vocalist of Asking Alexandria and We Are Harlot) was among the first Taylor artists to enjoy some extended playing time with a Gold Label guitar. Beyond loving the old-heritage voice and aesthetic, he was gobsmacked by the easy adjustability of the Action Control Neck.

“It is a massive deal,” Worsnop says. “When it comes to traveling musicians, it’s absolutely game changing. This allows you to do a micro-adjustment without having to get in the car and drive [to a guitar technician]. And when I’m in the studio, I like having that precision to be able to make it just perfect.”

Watch Danny Worsnop play his song “Ain’t No Use” on a Taylor Gold Label 814e featuring the Action Control Neck.

Climate Change, Action Change

As Worsnop mentions, the easy adjustability will be immensely useful for touring guitarists who travel to different cities and environments, where the temperature and humidity can fluctuate night after night.

When Taylor officially unveiled the Gold Label Collection at the NAMM Show in Anaheim in January, Rob Magargal had an opportunity to show the neck design to a few builders and repair technicians who attended. Among them was Singaporean luthier Hozen, a master guitar builder and guitar technician who is one of the best service providers for Taylor. He was impressed.

“With Andy being a player himself, it’s clear he understands what musicians truly need,” he says. “The ability to adjust the neck angle on the fly is a game-changer — especially for techs, as it makes their job significantly easier. I suspect that gigging musicians and their techs will appreciate the ability to recalibrate their action effortlessly as they travel through different climates. This feature also could be invaluable for players who want to refine their personal setup preferences or adapt to occasional seasonal shifts.”

As someone who’s adept at working with all types of neck joints, including the NT version of the Taylor neck, Hozen appreciates the evolutionary improvements of Andy’s design.

“Eliminating the need for shims is a brilliant step forward — it simplifies the process for repair techs, reducing the need to stock shims entirely,” he says. “It’s an amazing, player-centric innovation that aligns perfectly with Taylor’s legacy of pushing the boundaries of playability and serviceability.”

For his part, Andy is also happy with the stealthy nature of the innovation — that the design mojo is largely hidden to preserve a traditional look and produce a traditional sound rather than calling attention to itself in some unusual way.

“I love the idea that a player can simply pick up and play one of these guitars and be inspired by the way it sounds and feels,” he says. “And, while you’re at it, you happen to be getting the most precise, adaptable, easily adjustable guitar we’ve ever made.”