When I first came up with the title for this article, I thought, “This will be valuable! I’ll impart advice to players over the age of 50 on how to stay inspired and on track to becoming better players later in life.” But it quickly occurred to me that few 50-plus-year-old guitarists need more inspiration, as so many venerable guitar players today are well over the age of 50! So, let’s spend our time on more practical matters, such as exercises for stiff fingers (not to mention stiff bodies), gear modifications to make your instrument more comfortable (I’m looking at you, heavy gauge strings), and branching out into styles that you may not have explored.

Feeling Stiff? Then Start Slowly

Most of my students are significantly older than I am. Still, it wasn’t until I turned 50 myself that I started to become more sympathetic to older players’ needs. The clichés are true — your body starts to change when you turn 50 with things like stiffness, poor eyesight and hearing issues setting in, among others. Here are a few tips on how to deal with the changes that come with aging and their effects on your guitar playing.

Warm up thoroughly. Whether you’re a bluegrass flatpicker, fingerstyle enthusiast or bluesy bender, once you hit 50, you may start to feel that these techniques suddenly require more upkeep. But, in my experience, like an old car covered in frost in the winter, all you need to do is warm up a little more slowly. This will help not only with the stiffness in your fingers but will also help make you a better player in general. Playing slowly allows one to reflect on technique, execution and intention. That said, there’s no need for your warmup to be boring. Here are a few fun ideas to help get your fingers feeling limber.

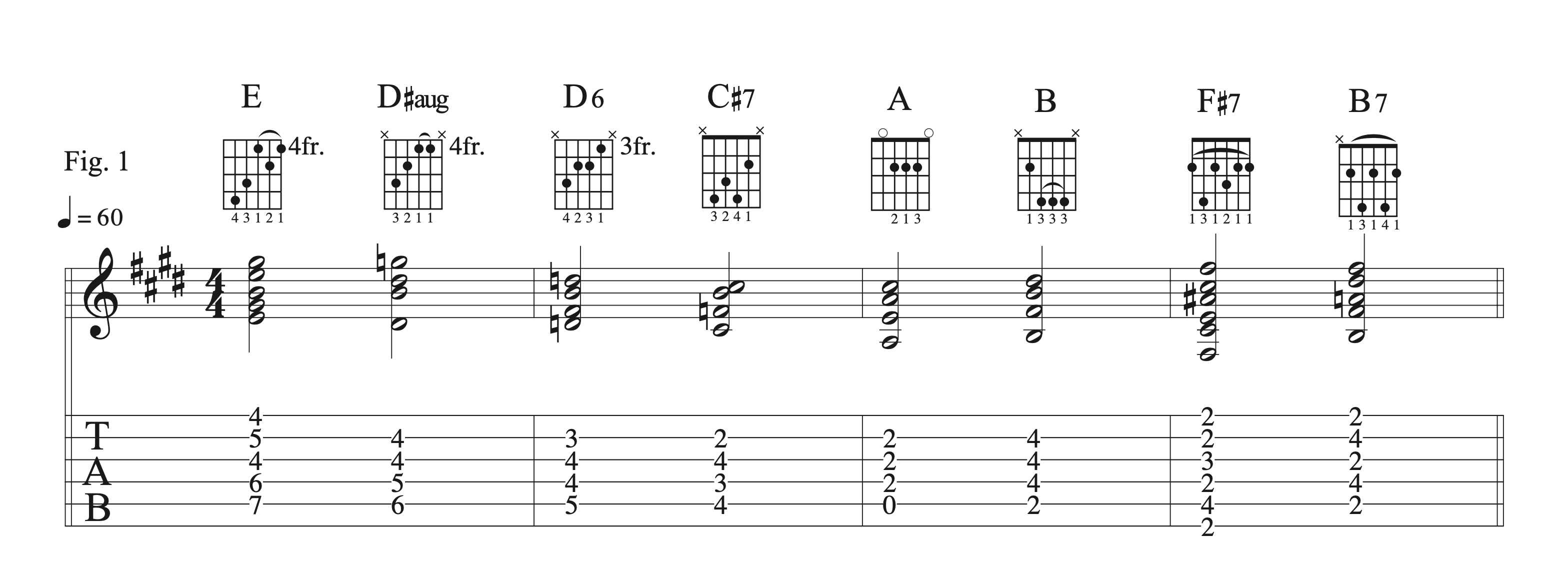

1) Learn a new song. Nothing fancy, something you can learn within five minutes using a chord chart or tab found quickly online. Pick a tune that will get you strumming with a new pattern, in a new order, or maybe with a new chord voicing. Of course, I recommend the Beatles (Fig. 1), but any song that’s new to you will do. The best part: You’ll never run out of new songs to try. If you’re having a hard time thinking of a new song you want to learn, just do an Internet search for the top 100 songs from any given year.

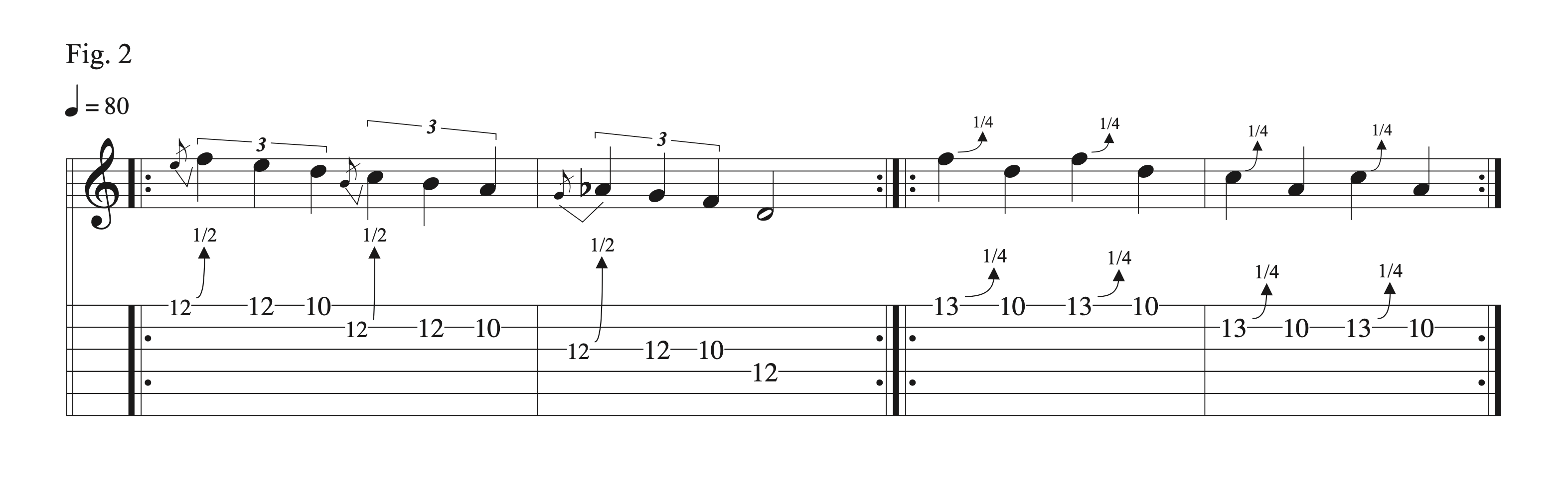

2) Bend in half steps or even bluesy quarter steps instead of whole steps. (Fig. 2) Whole-step bends can wreak havoc on fingers and muscles that aren’t warmed up. Practicing these bends higher up the neck is much easier than trying them in first position. These types of bends are applicable to virtually any genre.

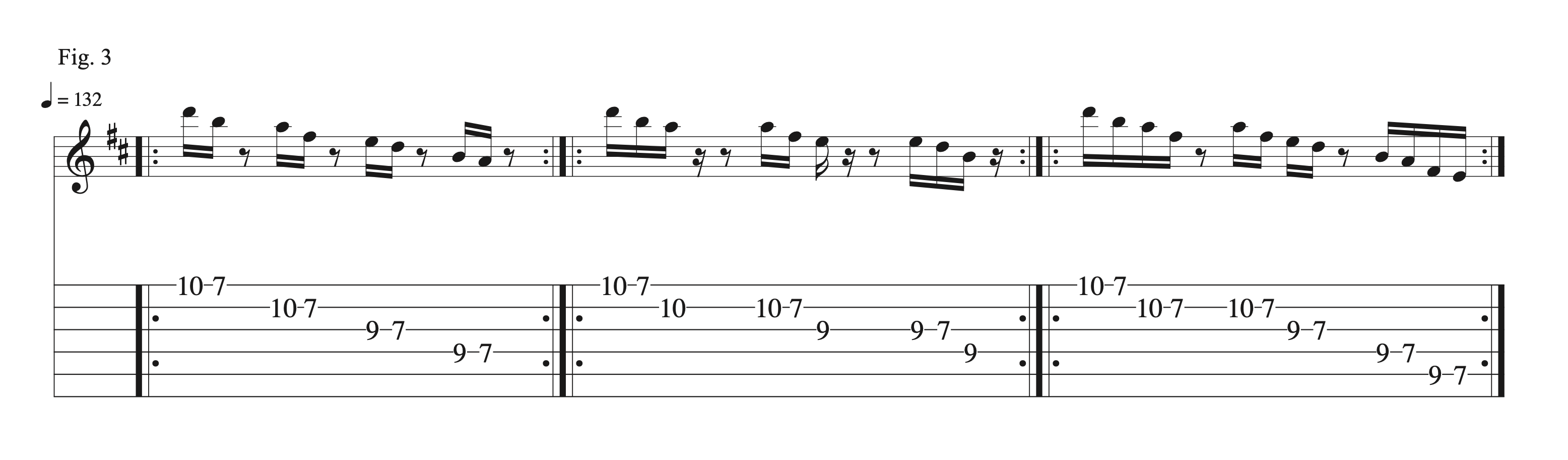

3) Play fast in short bursts. (Fig. 3) This is some of the best advice I can offer, no matter your age. Most guitar players can play two notes relatively fast — just make sure they’re clean and accurate. Once you’ve got those two notes down, try adding a third. Playing fast is more about endurance than it is actual speed, so work on building stamina gradually, one note at a time.

4) Attempt to play a moderately simple melody by ear. (Fig. 4…Try to figure out the end yourself.) This one is particularly beneficial if your eyesight isn’t what it used to be.

Speaking of vision concerns: If you’re a long-time notation/tab reader but have found the notes or numbers becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish, I recommend two remedies.

1) Start using electronic PDF files, which you can easily increase in size.

2) Get yourself a music notation program that allows you to make your own charts and modify any of their characteristics. For instance, you may have noticed that in the corresponding chart, the chord diagrams are bigger than usual, the quarter step bends are shorter than the half steps, the notation in line three is smaller than the other lines (ironically, I found shrinking the notation here made it easier to read), and the tab is larger than you usually find in magazines. Most of these modifications can be done with click of a mouse. Making songs easier to read will make them easier to learn.

Finally, regarding warming up and cooling down, remember to stretch your fingers frequently — before, during and after practice and play. (See my Summer 2015 Wood&Steel article “The Guitarist as Athlete” for specifics.)

Change Those Strings

For years, all I wanted to do was play, play, play. I didn’t care about setups, tonewoods, fingerboard radiuses or amps — I cared about the notes. Then, a few years ago, the manager of one of the bands I play in brought in a guitar tech and — here’s how apathetic I was regarding the care of my guitars — I asked, “Why a guitar tech? I know how to change my own strings!” Needless to say, the tech and I did not hit it off at first. Then she started setting up all my guitars. “Wait! This is how a guitar is supposed to play? And sound? What on Earth have I been doing for the past 30 years?!” I was shocked at what someone who was as committed to the playability of an instrument as I was to what was played could do with a hunk of wood and some steel. Readers, do yourself a favor and find a reliable guitar tech — someone who knows your playing style and respects your opinion, but who also understands how your guitar is supposed to feel and sound. If you’re like me and haven’t had your guitars looked at in years, I promise your guitar can and will play better.

Tech or no tech, there is one easy, inexpensive adjustment that makes any guitar easier to play as you get older: Change your string gauge. I don’t want to get into a debate regarding tone and string gauge, but it comes down to this: If your strings are so heavy that you can’t play well, then tone is a moot point. So, if your hands have lost some strength, try using a lighter gauge. While it’s true that strength training can help maintain and rebuild muscle, it’s also true that it’s normal to lose muscle mass as we age. You can also try mixing and matching gauges — lighter strings on top and heavier on bottom or vice versa. Just be sure to maintain playable action with a truss rod adjustment, preferably performed by a qualified tech. On that note, a tech may be able to improve your guitar’s action without changing the string gauge. Action is about personal preference, so experiment alongside a qualified and sympathetic tech.

Here’s one last recommendation on playability. If you still have trouble playing your favorite guitar even after a good setup, it might be worth trying a nylon-string guitar. Obviously, the strings themselves are softer than steel strings, and they also offer lower tension, decreasing the strength and effort needed to fret notes. Admittedly, nylon strings produce a different tonal quality, but as mentioned earlier, if you can’t fret properly, tone is irrelevant. [Ed. Note: Though nylon-string guitars have lower string tension, keep in mind that the necks tend to be slightly wider, so if you plan to explore this option, be sure to play the guitar to assess the handfeel.]

Stylistically Speaking

On multiple occasions, students have come to me specifically because they feel their playing has plateaued — that is, after years of practice, they simply aren’t getting any better. Oddly enough, many of these students have progressed so far in a certain style or a particular technique that they haven’t actually plateaued, they’ve simply mastered a skill. I would never say a player can’t get better, but at a certain point and a certain age, one can reasonably acknowledge, “Hey, I’m pretty good at this!” Sometimes, students can’t see the forest for the trees, and it’s my job to point this out. So, what is such a player to do? I believe there are two options:

1) Continue down the same path while adding to the player’s repertoire. For instance, a fingerpicker obsessed with Chet Atkins (who continued to play and record into his 70s) might explore the fingerstyle worlds of flamenco or classical, pursue the acoustic tradition of tapping and smacking à la Michael Hedges, or focus on jazz techniques such as those used by Joe Pass or the hybrid picking style of Mimi Fox.

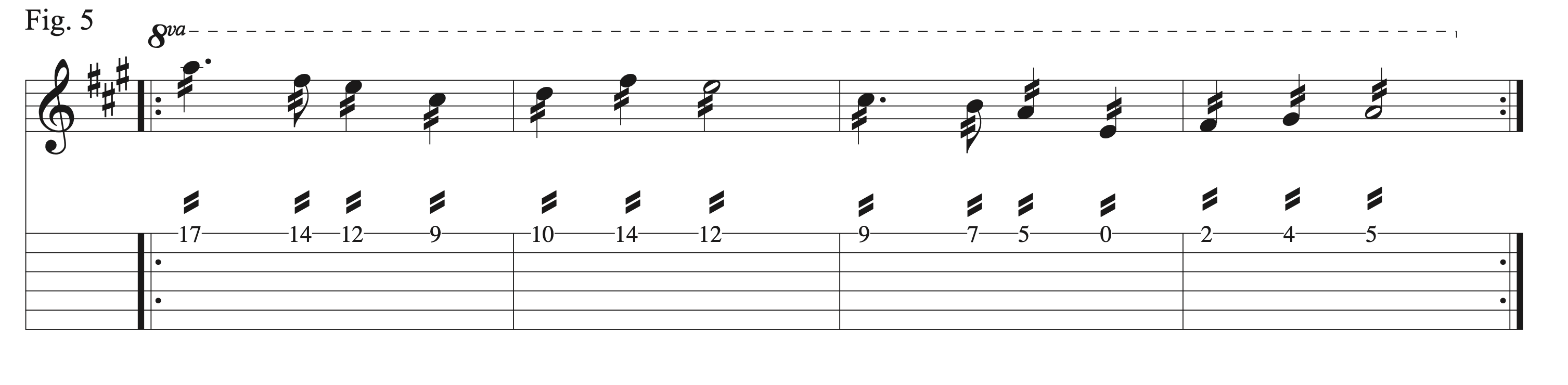

2) Change focus — but not too radically. If you’re typically a bluegrass flatpicker, try playing your favorite melodies in a surf style (Fig. 5). Maybe single-note, jazz improvisation has consistently been your passion, but you also admire the approach heard in Indian ragas. Don’t jump headlong into Hindustani classical music; rather, transition into the genre with John McLaughlin’s Shakti ensemble and their slightly more Western take on the genre. (I want to take a moment to highlight McLaughlin’s unbelievable performances from 2023, while touring at the age of 81. If you have not seen videos from this tour, find a few clips on YouTube. This is truly exceptional playing from any musician, no matter the age.)

Finally — and this is probably the best advice I can give any guitarist — if you haven’t already, start singing. Nothing will make you a better musician (“guitarist” is nice, “musician” is better) than singing, as you’ll internalize the music in a way that you won’t by simply playing guitar.

Here’s to 50 More Years

Our world is changing so quickly these days that it’s nearly impossible to predict how tomorrow’s music will sound. Between the Internet, computer music programs (from DAWs to notation software and countless others I’m no doubt unaware of) and AI, I am thrilled by the untold possibilities. But of course, the most important factor in the music of the future will certainly be the next generation of players.

My daughter is a talented bass player, and every day I see her growth as a musician. While I would like to take some credit, that growth is actually due to her high school’s music education program, playing among her peers and her own personal drive to improve. It’s by far the most inspiring and motivating factor in my current musical life. If you’re one of those old fogies who says, “Kids these days don’t know anything about good music,” you might be listening to the wrong kids.

“Youth is wasted on the young,” goes one adage, but my feeling is that getting older is wasted on everyone if you don’t make the most of it. After all, there is plenty of music left to be made.