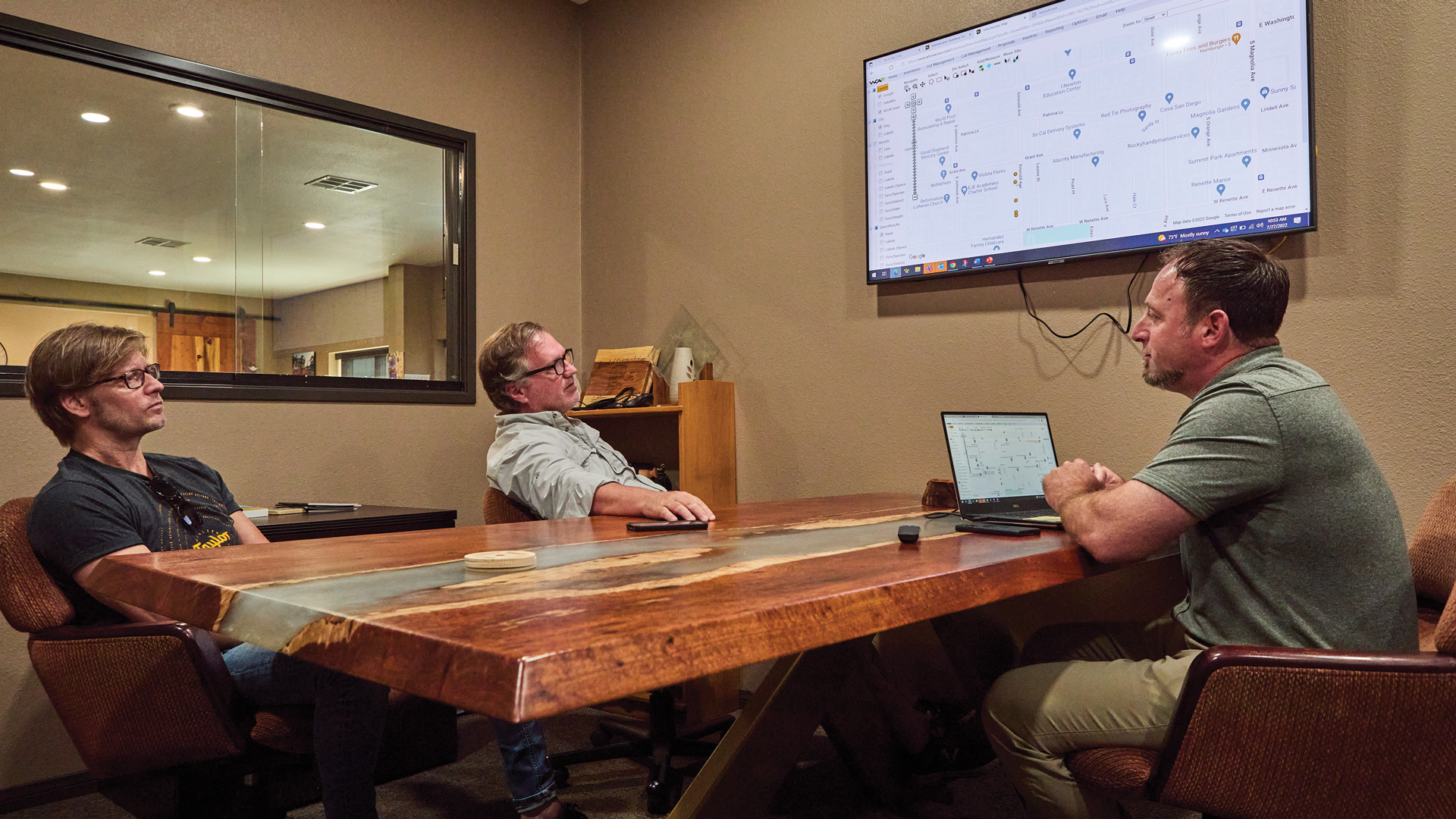

A few of us from Taylor are camped out in the office of Mike Palat from West Coast Arborists, who’s giving us a virtual tour of the proprietary information technology platform WCA uses to operate its business. All eyes are on a wall-mounted video monitor as Mike navigates WCA’s ArborAccess tree management software system, a robust database that integrates the detailed tree inventories and work histories they’ve compiled for the cities they work with — to the tune of nearly 400 municipalities across California and parts of Arizona. The system is used to document the life progressions of more than 6 million trees — with GPS mapping integration that tracks the location and work of their arborist technicians in real time.

Palat, a VP at WCA with 20 years of service there, is a board-certified master arborist with utility and municipal specialties, and he oversees WCA’s operations in the Southern California, southwest region, including San Diego County. He’s a walking Wikipedia of tree knowledge, and he’s happy to educate us non-arborists on some of the many considerations that go into urban forest planning and management.

The conversation ranges from the basics of what a municipal tree maintenance contractor does for cities to why WCA’s expertise has been so crucial to the collaborative urban wood initiative Taylor and WCA are forging together.

Our group includes Scott Paul, our in-house Sustainability expert, who knows Palat well and talks with him frequently. (Palat is Scott’s primary contact at WCA, and both sit on the Board of Directors for Tree San Diego, a non-profit committed to enhancing the quality of San Diego’s urban forest.) Throughout the demo, Scott peppers Palat with questions to help guide the conversation.

How Cities Manage Their Tree Populations

Palat starts by explaining how cities create and maintain their urban tree inventories. Within a city, he says, various agencies or departments may manage different classifications of trees that make up their public tree population. For example, in San Diego, the city’s Street Division oversees the maintenance of street trees. The Park & Recreation Department oversees trees in public parks. Trees near utilities (power lines) might be overseen by San Diego Gas & Electric. Together, all these trees comprise the urban canopy of city and suburban areas — trees that, for many of us, are hiding in plain sight, blending into the landscape alongside streets and buildings, but that actually are purposefully planted, documented and maintained.

“A lot of city asset management programs manage potholes, street lights, irrigation valve boxes — and also, trees,” Palat says. “Our software is very much their dedicated outlet for trees, and it’s specifically for cities. Cities have GIS — Geographic Information Systems — departments. For cities under contract with WCA, it doesn’t cost them any money to have their tree inventory housed in this program, and it’s dedicated toward the management of their tree population.”

A city that contracts with WCA might receive a range of management and maintenance services depending on their own departmental resources.

“Part of what we do is go out and collect the tree inventory for a city,” Palat says. “The cities own that data, and they can house it in a variety of ways. Our software, ArborAccess, is a web-based program that comes with a mobile app, so in essence what we do charge for is the data collection — sending out an arborist to go collect this information — but we don’t charge when it comes to the permissions of this program when an agency is under contract with WCA.”

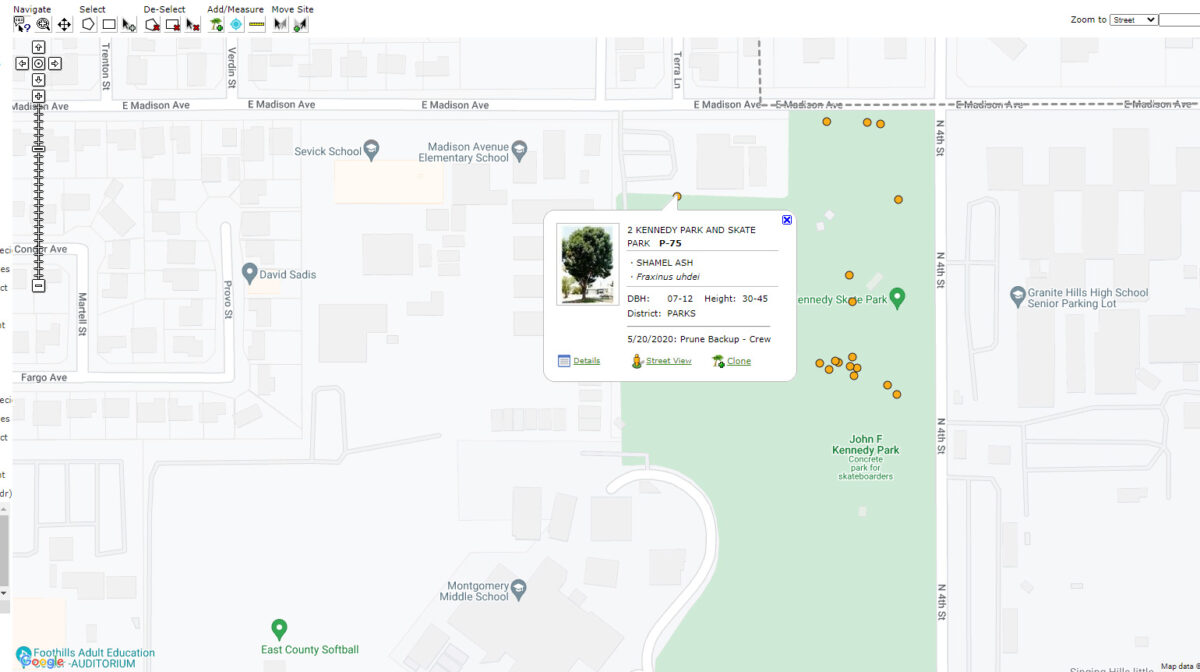

If a city has a maintenance contract with WCA, ArborAccess enables all the work history to be documented. As he talks, Palat pulls up a map of San Diego with GPS integration showing all the WCA crews that are currently working.

“You can see all the dots,” he says. “Those are GPS on the crew, these are all GPS vehicles, real time, where they’re working, where they’re parked, what time they got there, how their speed is — all that stuff is part of the program.”

Whether a city or WCA handles the documentation of the city’s tree inventory, a pre-qualified list is created and housed in the database, including maintenance recommendations on every single tree.

“Subsequent to that, if our crews are out performing tree-trimming work, if they see something, they update the data to inform cities that these trees have changed,” Palat says. “Trees are biological, so they’re always changing. So, that is one means of communicating the potentially risky trees to a city.”

While WCA is responsible for documenting the condition of trees and providing that information to the city, it’s ultimately up to the city to issue the service instructions. And when it comes to removing trees due to age, decay, safety risk, etc., that’s entirely the city’s decision. Scott underscores this point to make it clear that WCA — or Taylor — isn’t out scouting for trees to cut down.

“No, not at all,” Palat says. “We’ll give them recommendations based on our observations, but it’s ultimately their decision as to what trees come down.”

The conversation turns to the two urban wood species Taylor is currently sourcing from WCA — Shamel ash and now red ironbark — so Palat does an inventory search of both tree species in Taylor’s home-base city of El Cajon (a client of WCA’s) to demonstrate the usefulness of their system.

“There are 54 Shamel ash in the city of El Cajon, and if I want know where they are, I’ll map them, and here you go. I can turn on aerial imagery, and as you can see, when I click on a tree, it tells you what it is, gives you the details, the last time it was trimmed… you can see information about it — routine prune recommendation, no maintenance issues, and there is an overhead utility, so we can note that, which is not a good thing for a Shamel ash to be under.”

Right Tree, Right Place

This last point speaks to what has become a mantra for arborists everywhere: “right tree, right place.” In other words, from a planning and planting perspective, it’s important to plant species of trees with properties that are compatible with their specific location, and that serve their intended purpose, whether providing shade, sound breaks, wind breaks or other benefits, without being prone to causing problems. As in too being close to a sidewalk or street, where the root systems of certain species are likely to rip up the pavement or sewer lines. Or eventually growing to a size that will interfere with power lines. It often amounts to a geometry exercise, projecting what the tree may look like at maturity and how it ultimately will fill in the space where it will be planted.

“Wrong” trees planted in the wrong space eventually “become candidates for removal,” Palat says. “In fact, San Diego Gas & Electric has a whole program trying to rid these problematic trees, what they call cycle busters. They’re spending a lot of money doing vegetation clearance away from power lines, and a lot of times they’ll hit up agencies and basically say, we’ll give you free trees if you let us remove these.”

As cities look to plant more trees to bolster their urban canopies, they also have vacant locations mapped and designated as suitable planting sites. Palat zooms out on the map, showing an array of gray dots that depict those sites.

“If we’re doing vacant site analysis, part of that might be to measure a parkway width,” he says. “If there are overhead utility lines, all that plays into that decision-making too.”

The average life span of an urban tree is eight years.

Depending on the location, one of the challenges of cultivating a tree, Palat says, is determining who will water it. “Right now [in Southern California], that is the biggest struggle,” he adds. “Even if cities are willing to give trees away, nobody’s taking them. There’s contract watering, but that costs money. Or you might get a renter who says, I’ll take it on, but then they move and the new person doesn’t care. That’s a big reason why the average life span of an urban tree is eight years.”

There is also a large misconception about the cost of watering a tree, Palat says.

“Some people believe it costs thousands of dollars per year to establish a young tree,” he elaborates. “The reality is that it costs about 10 dollars per year to establish it. The gallons of water needed can be used in a strategic manner to maximize what is needed for establishment.”

It costs about ten dollars per year to establish a young tree.

A lot of a city’s tree planting decisions obviously need to consider long-term impact of the environments in which they live and grow. One increasingly vital forecasting consideration is how the effects of climate change are forcing cities to rethink the viability of their tree populations for the decades ahead.

To that end, WCA has worked with other tree experts in California to combine data and create an even more detailed statewide database with tree profiles and planting recommendations. One partner is Matt Ritter, a professor in the Biology Department at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, a horticulture expert, author and one of the world’s foremost authorities on eucalyptus. Matt’s online database, SelecTree, is a great resource for selecting appropriate species in California.

“The program we did with Matt brought in trees that nobody has heard of in an effort to gain some momentum on species that should be brought in for future success,” Palat says.

To show some of the other capabilities of their software, Palat pulls up the tree data for the city of El Cajon (where Taylor is headquartered) to give us a tree inventory overview. We can see, statistically, the top 10 most planted species by percentage of the tree population — crape myrtle leads the pack at 12.7%, followed by the queen palm at 12.2%. This data helps guide healthy diversification of the species planted.

“You really never want to have one species dominate more than 10% of your tree population, especially here in California,” Palat says. “Species diversity is important. The reason is new pests are introduced to California every 40 days, which makes your tree population vulnerable if it’s more than that.”

Age diversity is another important statistical consideration for evaluating the health of a city’s tree population, Palat says as he looks at the tree sizes to approximate the age of El Cajon’s trees.

“The fact that they have only .55% trees over 31 inches in diameter, it would be nice to have the age diversity be better spread,” he explains. “Typically when trees get into this large range, they become targets for removals — there are a variety of things that happen as the trees mature, everything from disease and pests to decay and not being an appropriate species for where the tree was planted.”

In talking about California’s tree inventory, one factor that has made the state such a hub of tree diversity is its Mediterranean climate (and micro-climates from coastal areas to inland valleys to the mountains), which can accommodate a wide range of species. And Palat points out that a lot of California, especially central and southern portions of the state, originally were essentially “blank canvasses” without a lot of tree cover, which is why many of the species are not native. (As an example, see Scott Paul’s Sustainability column this issue, where he talks about California’s history with eucalyptus.)

The conversation turns back to the urban tree species Taylor is working with, and Palat pulls up the location of some red ironbark trees in the area. We were hoping to shoot some photos of mature ironbark and Shamel ash trees somewhere nearby, and he’s scouted a couple of locations — one is a median strip along a road featuring several large ironbark trees; the other is a park that has both ironbark and Shamel ash.

Without WCA’s data analysis, Taylor wouldn’t be able to commit to using these urban woods on dedicated models.

Scott makes the point that WCA’s tree software made it possible for Taylor to commit to using ash and ironbark on dedicated models in our line.

“The big question for Taylor, beyond if the wood had suitable properties for guitar making, was whether or not there would be a supply over time, into the future,” he says. “The WCA database was able to show us that there are large numbers of the trees that we were interested in across the state, that they’re still being planted today, and based on the average lifespan of these species, WCA can give us a pretty good estimate of annual removal rates. It will ebb and flow each year, of course, but it gave us the confidence to move forward. If not for WCA’s ability to do that, we would never have been able to commit to using those woods as a regular part of our lineup.”

Since entering into this sourcing partnership in 2020, Taylor and WCA have continued to invest in processes and infrastructure that improve WCA’s operational capabilities with wood from removed trees.

“Now, we have a mechanism so when an agency issues a request to remove a Shamel ash tree, my phone buzzes, so we can make sure we communicate with the removal crew,” Palat says. “That reminds us to be extra careful in the way we take it down, and it ensures that it gets taken to our sort yard in Ontario [California].”

In this video segment — part of a longer discussion about sourcing urban wood — Taylor content producer Jay Parkin talks with Taylor Director of Natural of Natural Resource Sustainability Scott Paul, chief guitar designer Andy Powers, and master arborist Mike Palat from West Coast Arborists. The four discuss what an urban forest is, the factors that make sourcing urban wood harder and more expensive than one might think, and what prompted West Coast Arborists to begin to create the infrastructure to support this new sourcing model.

Taylor has also worked closely with WCA to properly preserve and cut logs in a way that’s appropriate for guitars.

“We’ve definitelylearned a lot from you guys,” Palat says. “We’ve built more shade structures, we’re now keeping wood wet — that was not a big requirement of us until we started working with you. And we’re now cutting in the manner that you’ve helped us establish.”

This infrastructure will ideally create the foundation for a circular economy around this wood, and hopefully serve as a model for making other high-value products.

Along with the other criteria that help determine what trees to plant in urban environments in the future, with any luck, maybe end-of-life value will become another consideration.