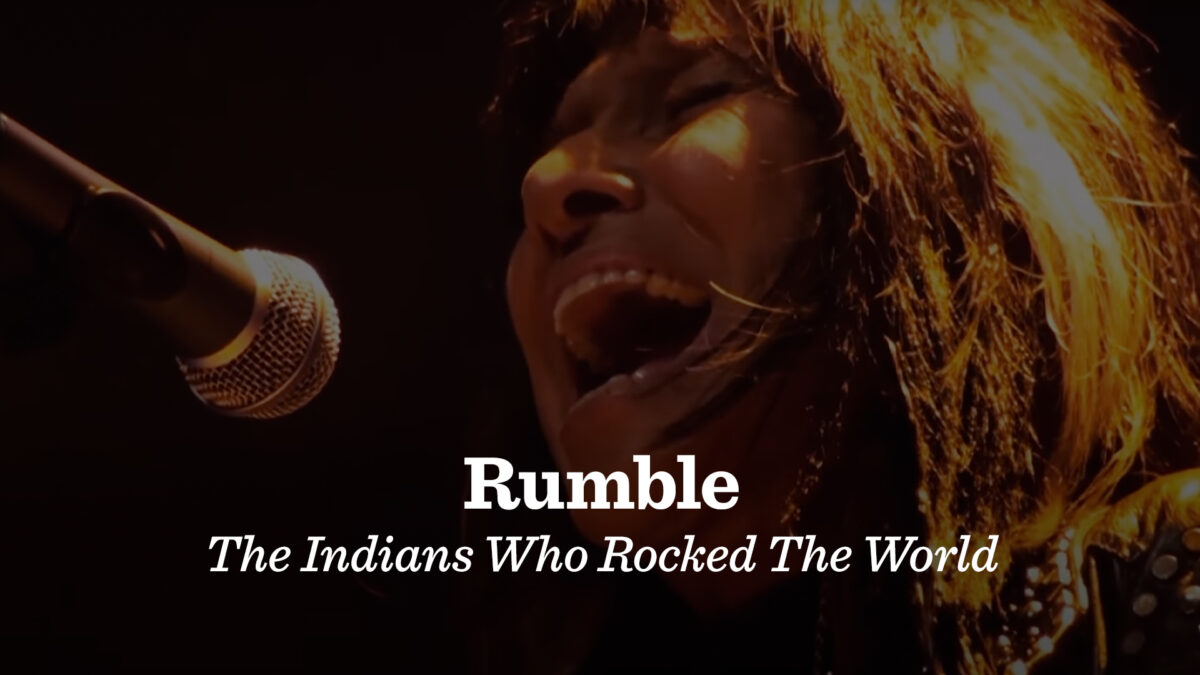

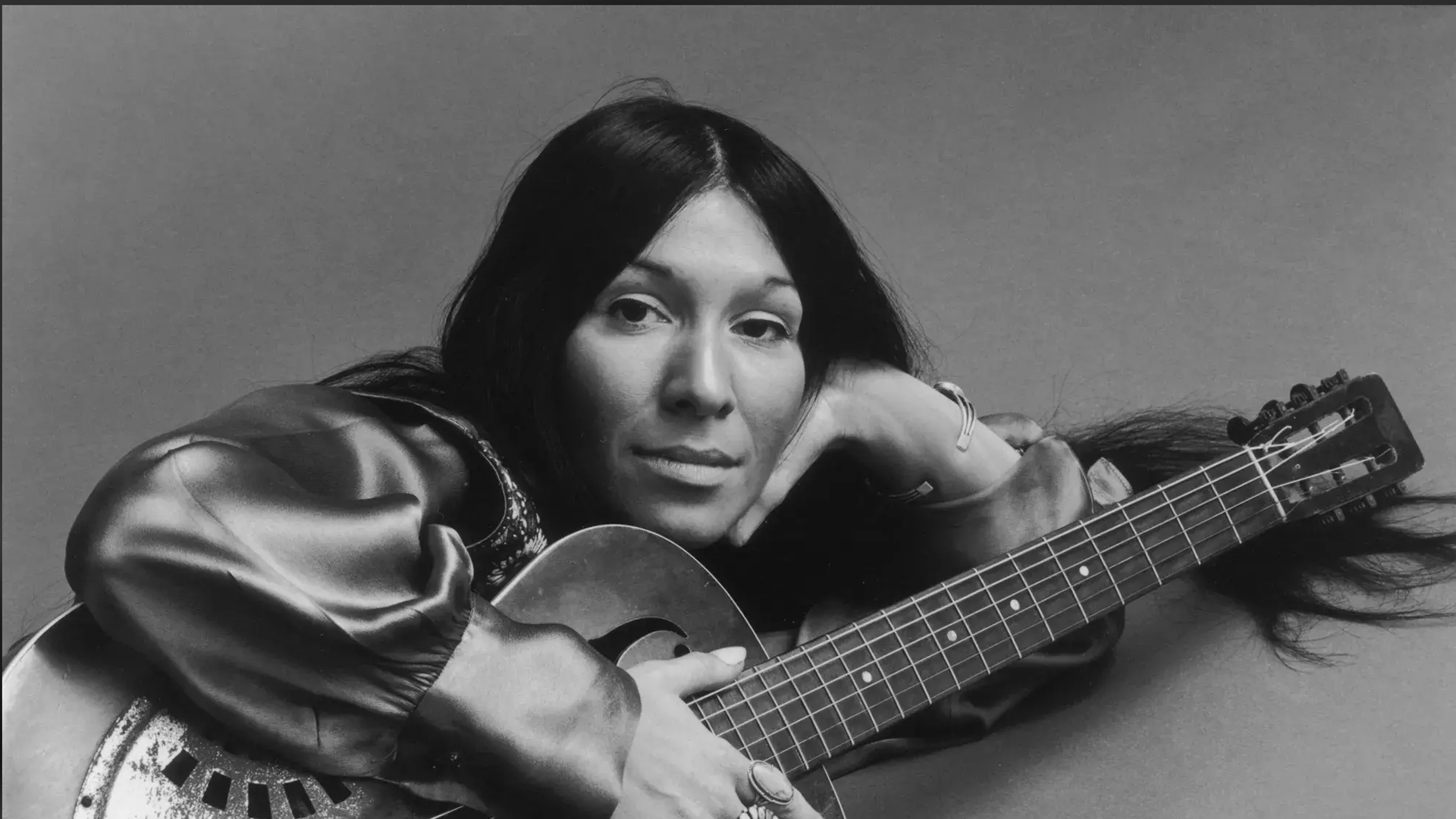

Picture this simple scene: On the left, a record player spins an LP. On the right, a woman named Pura Fé listens, her earrings and clothing subtly but clearly signaling her Native American heritage—Tuscarora and Taino. The music is rough, lo-fi, a classic blues recording by a singer and guitarist named Charley Patton, and when it plays, Fé laughs, her face lit up with recognition. She taps out the rhythm, and begins to sing along. A century and more of musical influence sparks to life, the connection indelible.

“It takes me right back to where I come from,” she says. “I can hear all those traditional [Native American] songs. That’s Indian music, with a guitar.”

This interview sequence of no more than two minutes reconstructs generations of sound passed across cultures and down through lineage—indigenous American folk music, African-American roots blues and a classic rock ‘n’ roll rhythm—all unmistakably linked in a way that’s so obvious that even an uninitiated listener can’t help but appreciate it.

That’s the power of the 2017 music documentary RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World, executive-produced by one Stevie Salas. Titled after the classic instrumental by Link Wray (Shawnee) and its thundering three-chord motif, RUMBLE is a rare film with a kind of restorative power, illuminating cultural threads once actively dismantled by the powers that be and bringing them into plain view for modern listeners. Awarded a handful of honors from independent film festivals upon its release, it’s an absolute must-watch for any fan of classic rock, blues or roots music of any kind.

Stevie Salas: Hands of Excellence

Watching RUMBLE, it’s clear from the outset that the film is a labor of love, imbued with an authenticity that elevates it from standard public-television fare into heartfelt, inspired craft. With executive producer Stevie Salas at the helm, it’s no surprise the movie delivers on its promise of rocking your world.

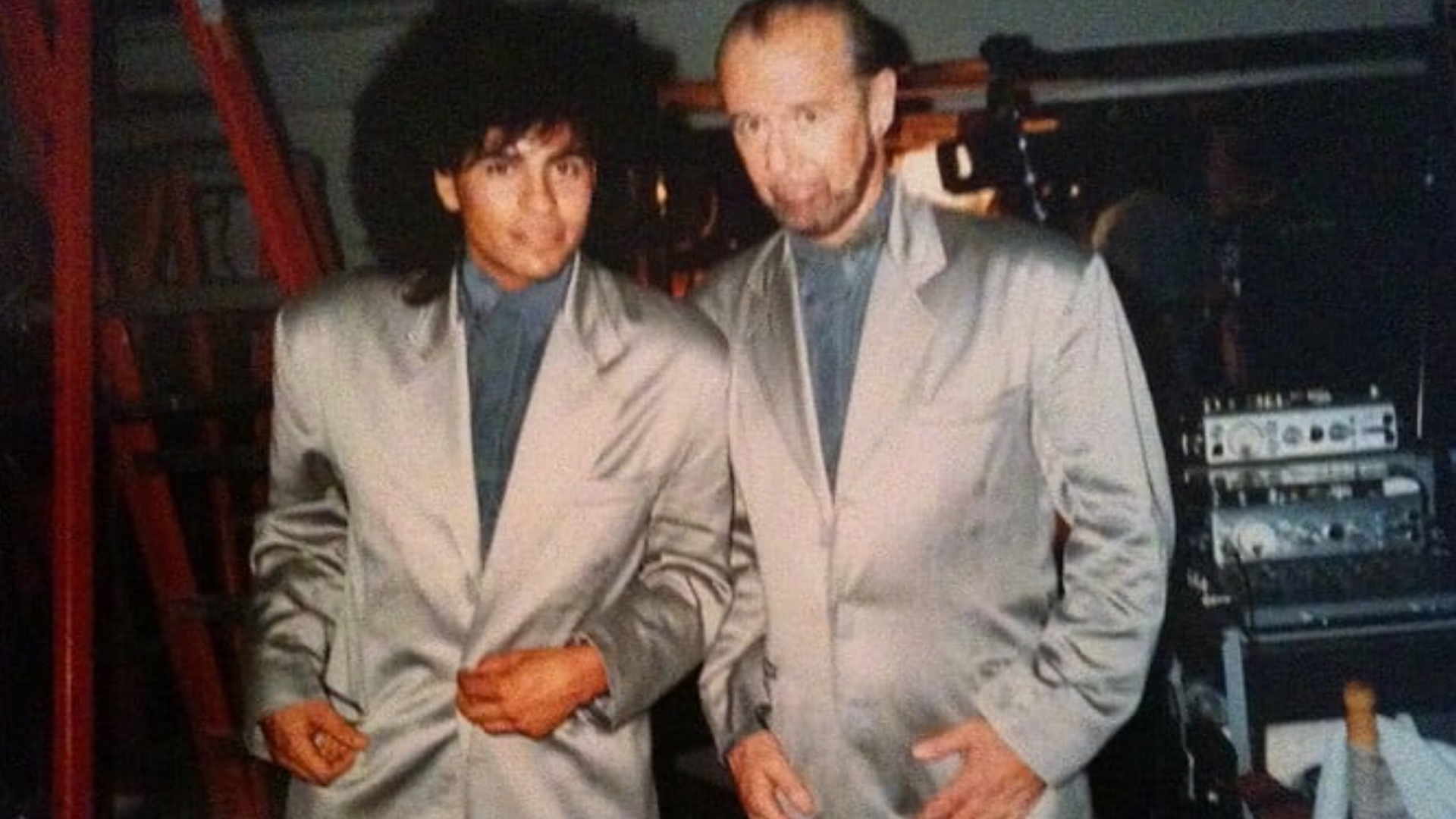

Born in 1964 in Oceanside, California—serendipitously close to Taylor’s San Diego home—Salas is the kind of musician who, in a more just world, would be a household name. In rock circles, though, his credentials are bona fide. Though he picked up his first guitar around age fifteen, Salas wasted no time kicking off his rock ‘n’ roll dreams, joining up as a session and touring guitarist with funk legends George Clinton and Bootsy Collins starting in 1986. Growing up on the sounds of classic staples like Led Zeppelin, Cream, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown and others, Salas credits the influence of his stepfather, also a rock musician, with pulling him into the world of music. Soon, Salas’s name was circulating among some of the era’s biggest acts, and he began touring with Rod Stewart in 1988.

Despite his stacked resume—which includes work with artists ranging from Mick Jagger, Ronnie Wood, Bernard Fowler and Steven Tyler to rapper TI and pop mainstays Justin Timberlake and Adam Lambert—Salas’s most recognizable sonic outing to many is an appearance in the cult-classic film Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. Starring a young Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter, the movie is a stoner magnum opus of the highest order, following two underachieving teens who, despite their dreams of hard-rock stardom, find themselves beset by mundane obstacles like high school and a total inability to play their instruments. Granted time-traveling powers by Rufus, a mysterious future-human played by George Carlin, the boys hop between eras in search of figures that might help them make the most epic history report of all time—which might just be enough to salvage their grades and keep their dreams of musical heroism alive.

Hijinks aside, Bill and Ted conclude their journey with an impromptu rock show fronted by Carlin’s Rufus, who plays a slick, if musically ludicrous, guitar solo to cap off the film. Seeking a bit of hard-rock authenticity, the producers hired Salas to perform the solo, and it’s his hands you’ll see on screen. To achieve the messy-yet-shreddy sound for the solo, Salas turned his guitar upside-down and played it left-handed while recording the audio.

An auspicious moment for a well-respected musician, Bill & Ted preceded a long career that brought Salas around the world to play with a laundry list of rock and funk greats. He kicked off his solo career with a project called Colorcode, which debuted with a self-titled album in 1990 produced by Bill Laswell. Salas followed by touring as an opener with Joe Satriani, and the album sold well globally. Salas went on to release six more studio albums as Colorcode, along with a pair of live albums.

I was never the guy that made my heritage a part of how I sold myself. The Native thing was who I was as a person in the background.

Stevie Salas

Salas has also recorded under his own name, and indigenous influence appears in much of his solo work. Apache by lineage, Salas acknowledges that for much of his career, his Native American heritage appeared in his work mostly filtered through non-indigenous players like Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, who themselves drew on Native sounds through the lens of American blues, a sound typically associated with the African American communities of the pre-Civil War and Reconstruction-era South.

“I was never the guy that made my heritage a part of how I sold myself,” Salas explains. “I wanted to be known as one of the greatest, and to work with the greatest, purely from what I was doing musically. The Native thing was who I was as a person in the background.”

Distant Thunder: How RUMBLE Came to Be

Salas recalls growing closer to his indigenous heritage when he began collaborating with Brian Wright-McLeod, a Dakota-Anishinaabe music journalist and radio host based in Toronto. Wright-McLeod exposed Salas to Jesse Ed Davis, a guitarist known for playing with Taj Mahal, Eric Clapton and John Lennon, among others. It was around that time that Salas decided to pursue cultural projects linking Native American musicians to the mainstream of popular music. Soon, Salas begun work with Tim Johnson (Mohawk), an associate director at Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian Institution, where he developed an exhibit on the theme titled “Up Where We Belong: Natives in Popular Culture” before beginning work on RUMBLE.

“I needed to do something, in the position I’m in as a Native American person,” Salas says, “to give back to the Native American people, to leave something other than me being a monkey jumping around on stage with a guitar. I needed to do something more important.”

RUMBLE premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2017, five years after Salas pitched the idea. It garnered immediate critical acclaim, netting the festival’s World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award for Masterful Storytelling. It also picked up awards at other indie fests, including Best Music Documentary at the Boulder International Film Festival and three Canadian Screen Awards in 2018.

An Interconnected Ecosystem of Music and History

In form, RUMBLE plays like most music documentaries, and its talking-head interviews interspersed with vintage and modern performance clips along with historical imagery dating back to the early 20th century will feel familiar to most audiences. Where the film truly breaks ground is in its remarkable commitment to unearthing connections between musical signposts that most people, regardless of their knowledge of music history going in, would likely have thought to be independent. RUMBLE carefully tracks features of musical styles from their conventionally understood originators back to hidden influences in American indigenous communities, like a biologist might discover invisible links between species in the long chain of evolution. The filmmakers manage to wring surprise and delight from stories many viewers may have thought they already knew.

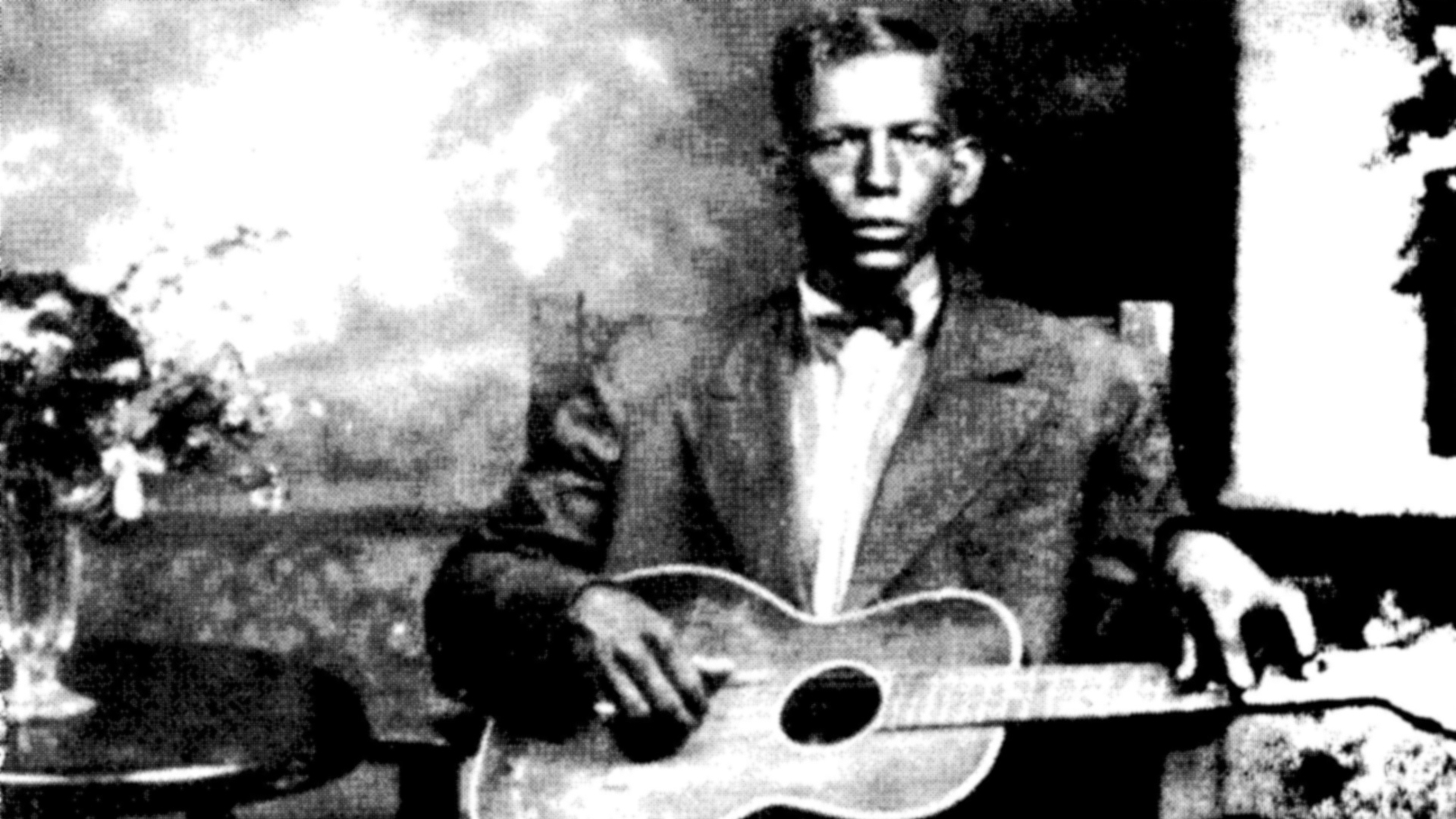

The most potent illustration of those connections dives more than a hundred years back into the history of indigenous peoples, African American communities and the United States as a nation. Take Robert Johnson, the influential guitarist whose playing is commonly thought to have formed the foundation of the blues, and by extension, rock ‘n’ roll of all varieties. But the real story is more complicated, and though Johnson’s influence is real, RUMBLE points viewers toward a different originator of the blues sound.

Quoting a conversation with friend, neighbor and fellow guitar player Charlie Sexton, Stevie Salas sums up the true history behind the well-known myth.

“Everybody talks about Robert Johnson because he had the sexy story,” referring to the crossroads legend of Johnson selling his soul to the devil in exchange for his musical talents. “But anybody who knows, knows that it was really Charley Patton.”

Likely born in 1891, Patton grew up in central and northwest Mississippi, close to territory inhabited by Choctaw indigenous Americans. He is thought to have Choctaw ancestry in addition to his African American heritage, a combination that was both quite common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and entangled with the racial politics of the time. As RUMBLE takes care to point out, Black and indigenous communities were often intertwined as a result of escaped enslaved people seeking refuge among tribal populations, among other causes. Native villages and communities often welcomed fugitive slaves and became integral parts of the famous Underground Railroad.

Charley Patton was immersed in these integrated Black and American indigenous communities, soaking up the musical styles of both peoples.

After the Civil War and the end of slavery in the United States, relationships between Black and Native peoples grew more complex. In particular, the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Creek tribes possessed significant percentages of people with Black heritage. To Reconstruction-era governments in the American South, this intermixing was often viewed as a threat, and racial discrimination continued. Often, African Americans descended from freed slaves and Native peoples had the full complexity of their lineages suppressed by the government of the time; mixed-race individuals were categorized as Black, and not Native, in order to deny their rights to land ownership. Likewise, lawmakers at the time sought to use this racial intermixing as a tool for eliminating tax exemptions for Native American communities.

Politics aside, Patton was immersed in these integrated communities, soaking up the musical styles of both peoples. Famously flamboyant in his showmanship, Patton was known for tricks like playing his guitar behind his head, a bit of flair that Jimi Hendrix would later adopt. Patton’s influence on rock music cannot be overstated—blues legend Howlin’ Wolf identified him as a primary influence, and Howlin’ Wolf himself was a font of inspiration for European musicians, the most well-known of which were none other than the Rolling Stones.

Stevie Salas describes this chain of influence as being hidden in plain sight.

“Once you started to look, all the information was there,” he says. “But none of us ever saw it.”

RUMBLE’s history lessons are wide-ranging in scope, covering the spread of musical concepts across an entire continent.

“We used the music to tell the story of how North America was developed,” Salas says.

Personal Bonds Across the Landscape of Rock

The film’s directors (Catherine Bainbridge, Alfonso Maiorana) and subject matter experts draw out the plot points in that story with great care. Illustrating Native American heritage and inspiration from Link Wray to Jimi Hendrix to Johnny Cash (who fought a protracted battle with his record label to release a collection of songs inspired by Native American culture), RUMBLE transforms sounds likely already well-known by fans of classic and blues rock into crossroads where ideas collided and grew into bedrock musical concepts. The film also explores the careers and influence of lesser-known musicians such as Jesse Ed Davis, whose bluesy solo on Jackson Browne’s “Doctor, My Eyes” turned him into a sought-after touring player; Redbone, whose 1974 hit “Come and Get Your Love” found a new audience four decades later after being featured in the 2014 Marvel film Guardians of the Galaxy; all the way up to Randy Castillo, hard-hitting drummer for Ozzy Osbourne and Mötley Crüe.

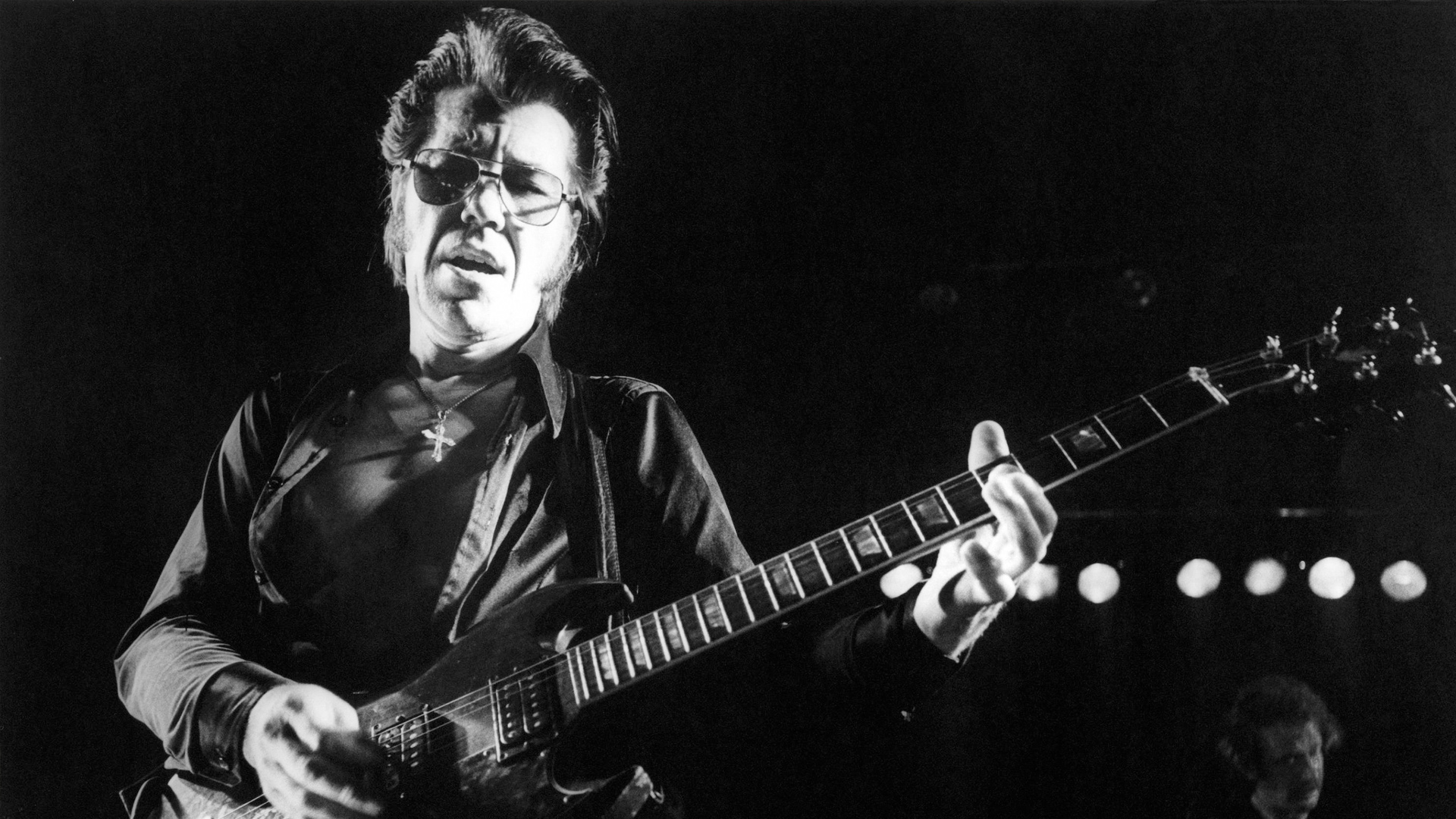

Castillo’s story has all the hallmarks of classic rock ‘n’ roll folklore: an unmistakable musical aesthetic that set him apart from other drummers of the time, a larger-than-life persona, a tragic ending. As RUMBLE draws to its conclusion, Stevie Salas himself steps in to tell Randy’s story alongside Native American poet and activist John Trudell (Santee-Dakota). Salas credits Castillo with bringing him closer to his own indigenous heritage in the 1980s, at a time when Salas was himself neck-deep in the rock-star life.

“I’m on a private jet,” Salas recalls. “I’m making tons of money, I’ve got all these women, but pretty soon, I don’t know who I am anymore. Randy Castillo befriended me knowing I was a Native American. He met me right when I was finishing the Rod Stewart tour. I was going deeper and deeper into alcohol and partying…and he could tell I was losing my mind. He said to me, ‘I’m gonna take you to New Mexico.’”

Salas says that for much of his career, he didn’t think of his Native ancestry as being a defining characteristic of who he was as a musician, or how he identified himself to the rest of the music world. But connecting with Castillo helped him connect with his roots.

“[Randy] goes, ‘I need to take you to Indian country,’” Salas says. “I’d never really heard that phrase, Indian country.”

A common thread throughout RUMBLE is the idea that there’s something musical shared between people of Native ancestry, a different way of approaching sound that let them carve out roles in the mainstream culture—and spread their influence down through the family tree of rock music.

“My Native American sense of rhythm, it’s in my DNA,” Salas says. “It’s a sense of how we hear the downbeat.”

The sentiment is echoed by the experts the RUMBLE producers chose to speak in the film, ranging from music industry insiders like Quincy Jones and Steven Van Zandt to well-known musicians like George Clinton and Taj Mahal to cultural scribes like Martin Scorsese and John Trudell.

Referring to Castillo’s time with Ozzy Osbourne, bassist Robert Trujillo recalls in the film how Ozzy sought out musicians who brought the distinctively “indigenous” approach to how they made music.

“Ozzy always said he loved working with indigenous people, Hispanic people. He had a connection with them,” Trujillo says. “He felt that they had better rhythm. He always mentioned Randy as being a direct connection to that indigenous energy and that rhythm that he loved.”

More than anything, Salas wanted to make a film that illustrated those connections between Native musicians and the now-universal understanding of rock as a genre. He says he was deliberate about not making RUMBLE a “race film,” instead wanting to make a film about heroes—the individuals who carried those sounds in their DNA and lovingly delivered them through generations of music.

In a recent Taylor Primetime interview with Salas hosted by the Taylor content team, he laid out his vision for the movie.

“RUMBLE was about people who changed the world,” he says. “What it was really about was how the people who taught all of us about rock ‘n’ roll learned from these [Native American] guys. If I told you Jesse Ed Davis was one of the greatest guitar players of the seventies, you might say, eh, he was alright. But if Eric Clapton says it, you say, maybe I better think about this.”

Even with its somber recollections of historical wrongs and reckoning with the challenges faced by Salas’s ancestors, RUMBLE is unquestionably a rock documentary of the best kind. Drawing together disparate threads of history and culture into a tight, compelling timeline, RUMBLE makes explicit the lines of influence previously known only to music historians and the handful of players who actually worked with these Native American heroes of rock. Much more than a niche documentary, RUMBLE is essential viewing for any musician or listener who wants to understand how rock became what it is today.

Taboo (Shoshone) of the pop band the Black Eyed Peas sums up the message near the end of RUMBLE.

“When you’re surrounded by beautiful people that come from the Nations and they’re proud of their heritage, it just inspires everybody.”