In March, Fast Company named Taylor Guitars one of the world’s most innovative companies in the manufacturing sector. Citing our global environmental and sustainability efforts, we were honored to be included at no. 9 of the Top 10. It became official while I was attending the seventy-fourth meeting of the Standing Committee for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in Lyon, France. It felt appropriate to receive the news at a CITES meeting, as in many ways the award is a reflection of the changing landscape for makers of musical instruments, the very reason I was at this meeting. Sitting behind my Taylor Guitars placard in the back of a large auditorium, I thought about that changing landscape and about how I, a former Greenpeace Forest Campaigner who was once arrested for Sailor Mongering, came to represent a guitar company at multilateral treaty negotiations aimed to ensure that international trade does not threaten plants and animals.

The last time I attended a CITES meeting was for the 2019 Conference of the Parties (CoP) meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, when an informal group of musical instrument interests successfully lobbied to amend the rosewood listing to permit finished musical instruments, parts and accessories to be exempt from requiring CITES permits. (To learn more about the history and resolution of the CITES rosewood listing, see the article “Rosewood Musical Instruments Exempted from Requiring CITES Permits” in W&S Vol. 95, Fall 2019.)

Buying wood for musical instruments in 10 years is going to be very different than it was 10 years ago.

Under normal circumstances, there would have been several in-person intersessional meetings following the Geneva CoP, but we haven’t exactly been living in normal times since the pandemic hit. In fact, this meeting in Lyon was the first time CITES has met since then, and it will be the last time before the next CoP in Panama later this year. Only a CoP can make changes to the Convention, and due in part to the lack of meaningful consultation over the past two years, it’s anyone’s guess whether significant changes to the Convention, such as listing new species, will be adopted. Regardless of what happens in Panama, new CITES tree listings are coming in the future, and it’s inevitable that some will be species that are used as tonewoods. The landscape is indeed changing.

Taylor Guitars fully supports CITES. We are not opposed to additional CITES listings or any legislation designed to protect forests and bring greater transparency to the forest products trade. Like everyone else, we simply want policy to be scientifically justified and the language shaped by consultation with issue experts and affected parties. To achieve this, the musical instrument community needs to “be in the room where it happens,” as the saying goes, because change is coming, whether our industry is paying attention or not.

From How It’s Always Been to How It Has to Be

For some 200 years, the music industry has enjoyed access to a reliable supply of largely old-growth wood, but, relative to other industries, instrument makers have consumed a very small percentage of it. In fact, in the grand scheme of things, the industry has always been too small to influence international trade patterns. Even now, I estimate that the global guitar industry uses less than one-tenth of one percent of the global trade in the species we use, with the only exceptions being koa and ebony. But for the purposes of this article, our historical consumption is irrelevant. The only thing that matters is that today, the global forest estate is shrinking and becoming more fragmented, and that buying wood for musical instruments in 10 years is going to be very different than it was 10 years ago.

When it comes to sourcing tonewoods, I’ll always remember Bob Taylor saying that during the course of his career, he feels like he has stepped through the doorway from how it’s always been to how it has to be.

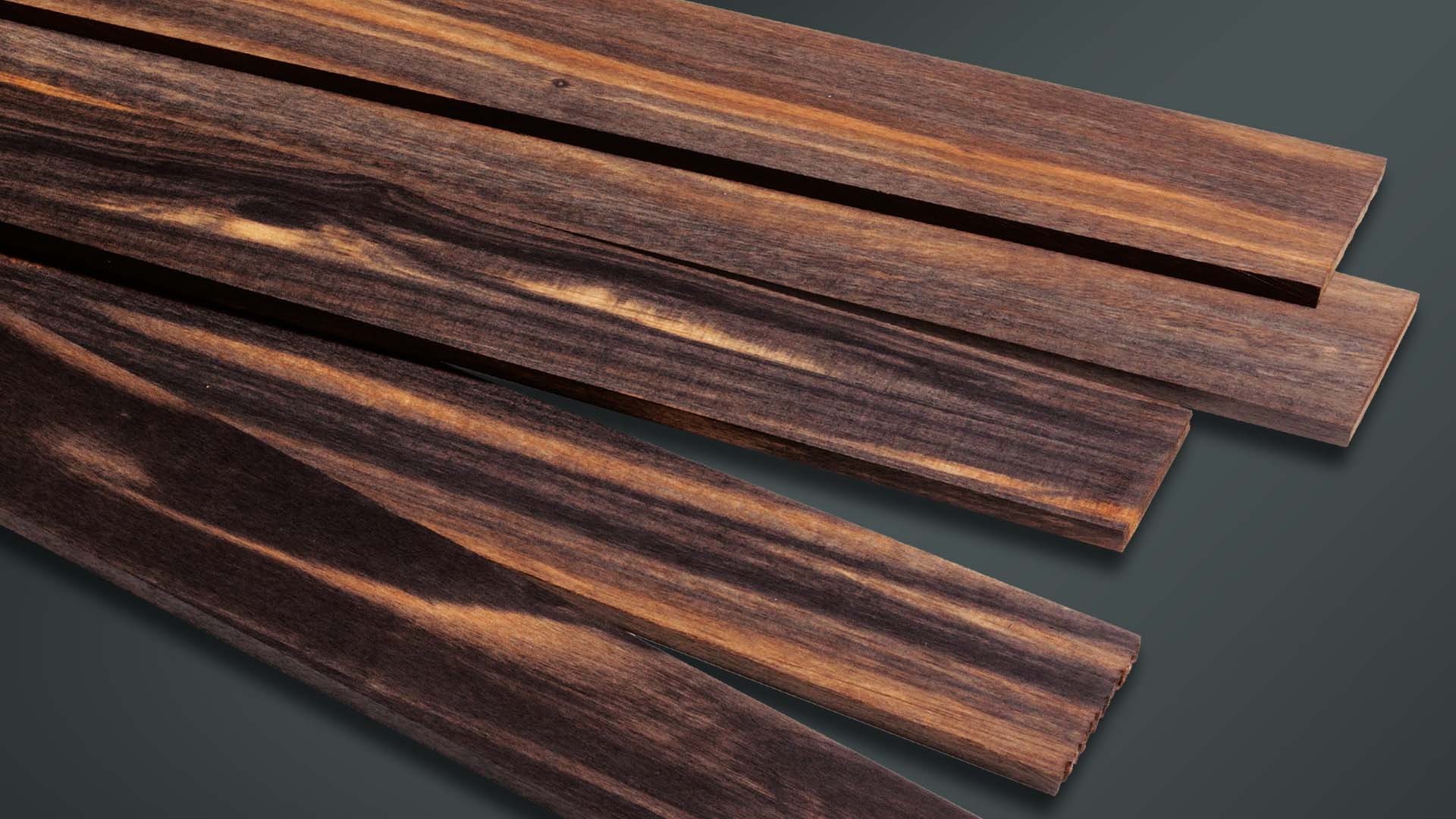

Consider for a moment that in the last few years, Taylor Guitars pioneered the use of variegated ebony fingerboards and has incorporated Southern California urban wood into multiple product lines. We have increased our use of both domestic and plantation-grown species. We also continue to expand our palette of species used for guitar tops, and we are preparing for a future where four-piece spruce tops are far more commonplace.

Why four-piece tops? Simply put, as currently distributed, there are not enough commercially available large-diameter spruce trees to supply two-piece guitar tops for all the guitars made in the world moving forward. Theoretically, there are, but only a fraction is suitable to build instruments, and the vast majority of what is taken is sold to other sectors for construction, fiberboard and wood fuel pellets. Of course, there are also impressive stands of spruce in protected areas (a fraction of what once existed) that will hopefully never be touched.

There are two reasons why two-piece guitar tops became traditional. First, because large-diameter spruce had always been plentiful, and second, because a two-piece top required less work to make (fewer pieces to saw and fewer joints to glue). With fewer large-diameter, high-quality logs being directed toward guitar makers, it simply means we will need to adapt and embrace the task of doing more work to fabricate a high-quality guitar top — the way piano makers do. (A piano soundboard is constructed with many planks of spruce.)

We will be talking more about four-piece spruce tops in the future, but the point is that all of this innovation (i.e., variegated ebony fingerboards, urban wood, plantation wood, more domestic species, changes in design and build, etc.) is happening at the same point in history and for the same reason. The traditional forest resources that we have always relied upon, with little forethought, are changing, and in some circumstances, we are coming to the end of the commercially available supply, at least in the volume and grade we are long accustomed to.

The Three Horsemen of Forest Loss

For over 150 years, luthiers used small amounts of largely old-growth wood sourced from different regions of the world brought to market mostly by other larger industries who sourced wood to build ships, planes, buildings and furniture, to name but a few. For a luthier, wood from both temperate and tropical regions has always been plentiful, and particular species were selected for their acoustical considerations, physical properties and workability. But as each decade passed, as the human population grew, as technologies advanced, as global markets become more interconnected and forest cover decreased, many of the industries that drove the forest products trade changed. Some substituted one species for another or adapted to faster-growing plantation species. Some industries changed materials altogether, switching from wood to metals, concrete, plastics or composites. But for musical instrument makers, such change is not so easy. Tradition is valued, and technical specifications are rigid.

Still, everything was fine for luthiers, much like it had always been, until just a few decades back when some started seeing horsemen in the distance (metaphorically speaking). You see, when it comes to buying old-growth forest products, telltale signs of trouble are changes in price, quality and geography — what I call the three horsemen of forest loss. If you see one, things are probably OK, but if you see all three, you’ve got a problem. Of course, your ability to notice such things will differ depending on the volume and regularity of the wood you buy. For example, if you’re a luthier and produce five guitars a day, you’re far less likely to notice than if you produce 500, or even a thousand.

In an industry dependent on quality wood of exacting standards, if you start seeing the horsemen, you have two options: You can close your eyes and pray or you can innovate. If you’re a luthier, it might mean breaking from traditional approaches to building, incorporating variegated ebony, using urban and plantation wood, expanding your palette of top species, and making some four-piece tops, for example. The world is changing, and in the words of Taylor master builder Andy Powers, “You don’t know what you can make until you know what you can make it from.” I find that an interesting comment from a guy whose career will largely take place on the other side of the aforementioned doorway that Bob Taylor has stepped through during his career.

Invest in the Inevitable

Taylor Guitars has always innovated and adapted to change, and the quality of our guitars keeps getting better. And it will continue to — that much I know for sure. There is no denying that it’s getting harder to get good materials to build guitars. Moving forward, wood supply will increasingly be an important factor that will require us to further adapt. But in addition to manufacturing innovation, the industry needs to start taking the long view when it comes to forest management, looking ahead 30, 60, 100 years or more.

The world is changing, and in the words of Taylor master builder Andy Powers, “You don’t know what you can make until you know what you can make it from.”

The Ebony Project in Cameroon, our koa work in Hawaii with Pacific Rim Tonewoods (PRT), PRT’s own pioneering work with maple in the Pacific Northwest, and Taylor’s urban trees partnership with West Coast Arborists are all steps in this direction, but they need to grow into more. Other manufacturers and organizations are engaged too. In fact, next to me here at the CITES meeting are representatives from the League of American Orchestras, the International Association of Violin and Bow Makers, and the Confederation of European Music Industries.

Other well-known manufacturers have attended meetings in the past and, collectively, our industry must continue to engage in these international discussions and also find innovative ways to give back to help expand forest cover, diversify forest ecosystems, grow trees with superior genetic traits, and use our influence to drive forestry that focuses on high quality in order to rebuild the extraordinary resources that gave rise to our industry.

Scott Paul is Taylor’s Director of Natural Resource Sustainability.