Andy Powers and I have bellied up to a big, beautiful work table in the middle of his newly renovated workshop on the Taylor campus to talk about the state of guitar making at Taylor. The studio space is an ideal setting, sure to inspire anyone who loves wood and woodworking — tidy, spacious, filled with natural light from floor-length windows on one side. The shop is appointed with a mix of handsome custom-built worktables and storage cabinets, all crafted with off-cut pieces of sapele, blackwood, ebony and other wood that couldn’t be used for guitar parts, including the checkerboard-style ebony-and-sapele flooring. The vibe is refined-rustic — warm, unpretentious and highly functional.

Ultimately, what you hear from an acoustic guitar is a composite of all of its elements.

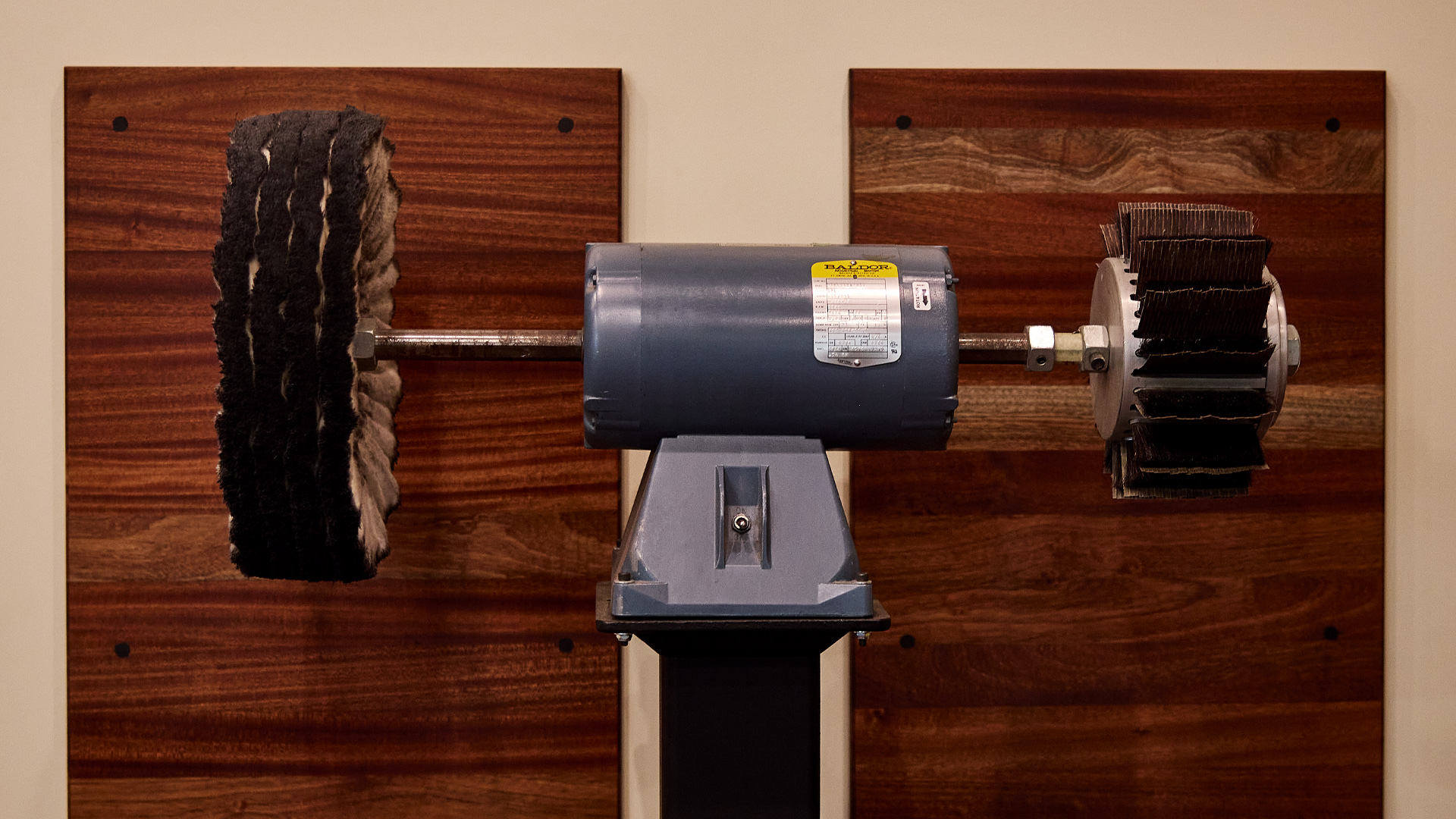

Every component in the room is thoughtfully arranged, from wall-mounted racks cradling select sets of guitar wood for future prototypes to a wooden A-frame unit that houses an array of clamps to sanders and other essential machines, including a workhorse Davis & Wells bandsaw built pre-World War II that Andy loves.

“Bill Collings turned me on to those,” he says, proudly expounding on the history and superior performance virtues of the unit. “I’m fortunate to have one at my home workshop too.”

As a craftsman, Andy says he’s always had an appreciation for the environments people create to live and work.

“My dad’s been a carpenter my whole life, though the closest I get to the family business is working on my own house,” he says. “Since I carry that background with me, I think it’s interesting to see the spaces people create for themselves — it says something about the way people live, the way they see things, the way they want to experience things.”

It’s not lost on Andy that so many of us have been forced to radically change the way we live and work over the past two years in the wake of the pandemic. If there’s any silver lining to this collective reckoning, it may be the way it has caused us to reconsider our priorities in life, perhaps gain a fresh perspective, and look to reboot our lives in more meaningful ways.

Some people decided to learn to play guitar; others returned to it after a long hiatus. In Andy’s case, he seized the opportunity to not only redesign his workspace but reflect on his relationship to making guitars.

We don’t all play alike, we don’t all listen alike, and I don’t want to build all our guitars exactly alike.

“I can tell you I’m more thrilled with building guitars now than ever,” he says. “I’ve been doing it for a long time, and I continue to love it. As with any long-term relationship, with time, there come shifts and growth. I think it’s important to step back, look at the instrument and think, how do I approach it now? How has this relationship developed? Even the component parts are worth considering — we’ve worked with thousands of pieces of mahogany or maple or spruce, but it’s good to pause and think, usually we do this, but what if we did this? I feel like there’s still a lot to discover about wood and the instruments we make from it.”

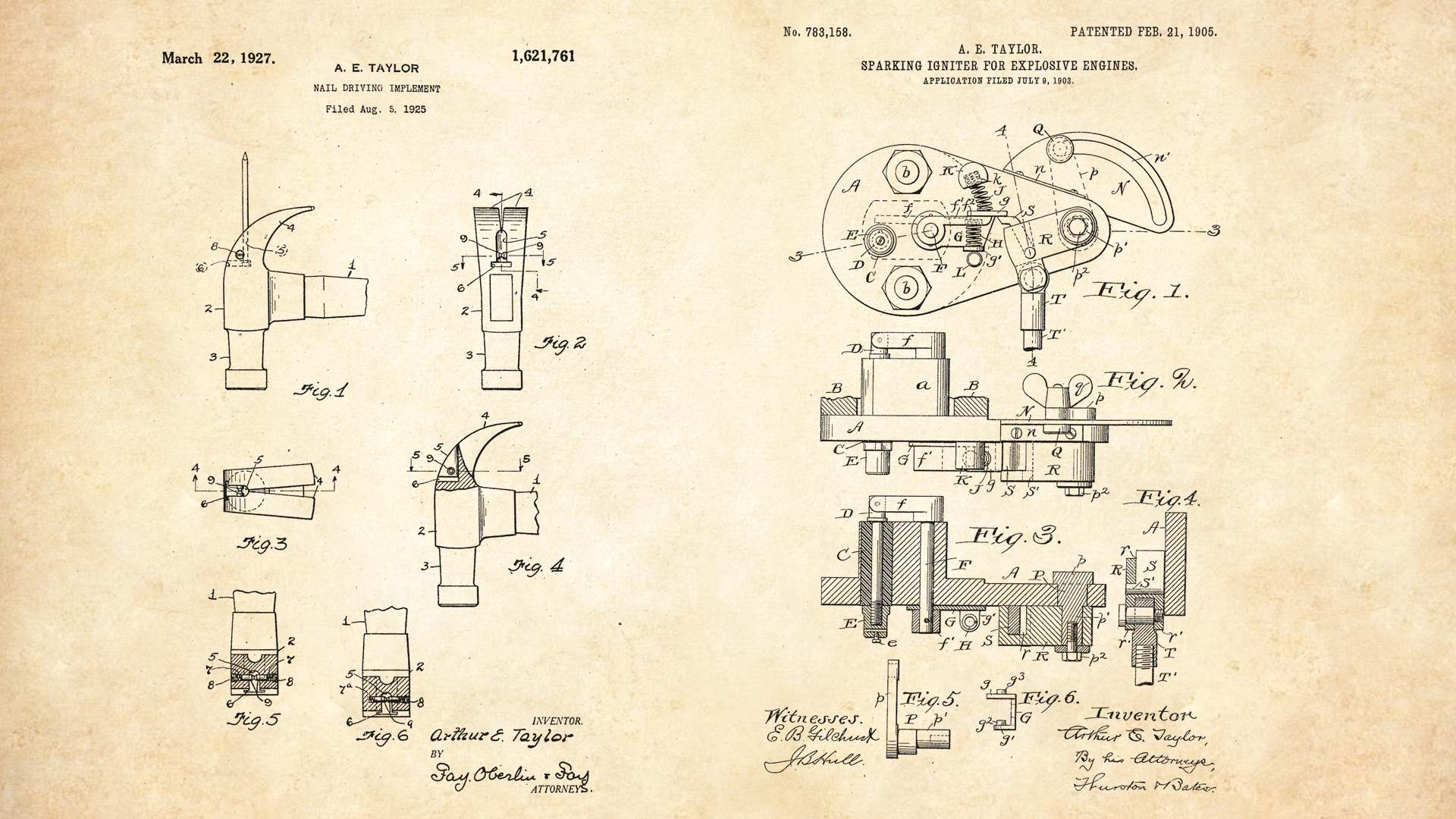

Besides sharing a love of woodworking with his father, innovation is apparently another trait in Andy’s blood. He gestures to a wall adorned with framed reproductions of hand-rendered patent drawings of inventions by his great-great-grandfather, Arthur Taylor (yes, his last name was Taylor) from the early 1900s. They range from a sparking lighter for internal combustion engines to a hammer head with a nail-driving device built into the claw end that would allow a person to start a nail with one hand.

“It’s fun to glance at those drawings and think about how he was looking at something as familiar as a hammer in a fresh way to improve its function,” he says.

—–

Since this is our guitar guide edition, we thought what better way to set the stage than by taking a step back along with Andy to talk about his design pursuits at Taylor, how our guitar line has evolved, and where he sees things heading. One thing seems certain: Thanks to Andy’s envelope-pushing designs, we’ve never had a more diverse assortment of musical personalities represented within our guitar lineup.

You’ve been at Taylor 11 years now. Looking back, do you feel like you arrived with a particular creative mission or mandate that was agreed upon between you and Bob?

We didn’t start with a mandate or marching orders from a design perspective other than to say we wanted the guitars to be more musical. We think of that as the noble path, so to speak. Our job as guitar makers is to serve the musician. I love when instruments are collectible, when people appreciate the instrument for the instrument’s beauty, but our purpose extends to a guitarist making music. At face value, playing music is a very impractical thing, yet I think it’s utterly essential in that it’s a way for people to make sense of the world and express themselves. As an extension of this, I want every one of our guitars to serve a musical purpose.

And those purposes may vary from guitar to guitar.

Each guitar should serve a unique purpose. They can’t and shouldn’t perform in the exact same ways. When I go through our entire catalog and play all the guitars, one theme that stands out to me is all the instruments sound fundamentally musical, like guitars should. Beyond that, we don’t listen to them all in the same way. Some sound more intimate, some sound large, some project really far, some are very touch-sensitive, some sound warm, dark or moody, some are vibrant and cheery. Some are guitars you want to listen to in a beautiful, quiet room; others you want to walk onto a large stage with. They all have different purposes and personalities, and that’s where I see the value in building guitars of different kinds. There are a lot of variables that make an instrument uniquely appropriate for a certain thing.

When you joined Taylor, I’m sure you were familiar with our guitars, but did you see an immediate opportunity to further diversify our line?

Yes, I saw a clear opportunity to further develop our portfolio. If you glance back at the guitars we made 15 years ago, you’ll see a lot of similarities in construction. We would primarily change the outline and the wood on the back and sides as the two big variables to alter. Many of the parts inside were identical to each other. Some would get re-shaped in minor ways to fit, but many were very similar. To me, that felt like an opportunity to expand and yield a broader portfolio of sounds.

Plus, you came from a custom-building background, where every guitar you made was crafted specifically to fit the needs of one person.

Yes, my experience had been on the other end of the spectrum with respect to production. When a person would come to me and ask for a guitar, I’d say, “Before we decide whether this is to be an archtop guitar, a flattop guitar, an electric or whatever it might be, what do you want to sound like? What are you listening to? What kinds of sounds do you like? What kinds of sounds don’t you like?” With the table set, we’d start making choices to make an instrument that would result in the desired outcome. Steeped in that background, musical variety remains a great interest for me. I like diversity among musicians, in musical styles, in songwriting styles, in performing styles. I think that’s great. We don’t all play alike, we don’t all listen alike, and I don’t want to build all the guitars exactly alike.

Eleven years in, as you look at our guitar line, how do you evaluate it in terms of what it’s become?

I’m proud of the state we’re in as guitar makers. When we look at all the models we make, there is a significantly broader range of sounds available now than ever. A bigger range of appearance, of musical function, of tone, of feel, all standing on the foundation of certain qualities we want to remain consistent. Those foundational qualities are what Bob would describe as the objective elements he sought for decades. I’d describe them as the must-haves. The guitar has to play well. The setup has to be great, the neck has to be straight, it’s got to be reliable, it’s got to be accurate, the notes have to play in tune. The mechanics of each instrument have to be fundamentally solid. Only after these are established can you consider the sounds the guitars are making. With modern equipment, you can evaluate sonority using spectrum analysis and things like that, but I find it more useful to evaluate sounds the way an artist would interpret them. With a particular guitar, you could use technical terms and say it has sensitivity of a certain amount centered around so many hertz [the unit of measurement for frequency], but what I feel is, this guitar is sensitive to the way I touch the strings. Or this guitar feels very emotive because I can articulate it delicately, I can play it forcefully, I can play it with a solid hand or a gentle hand, and it’s responsive that way. Each design feels like an invitation to play with a certain emphasis. With one of the current Grand Orchestra guitars, you feel like grabbing a thick pick and laying into it — that is a strong, bold sound, the triple espresso of guitar sounds. It’s powerful. I like a variety of sonic colors and want to be thinking about them in terms of how they make me feel as a musician.

We’re a few years into the V-Class bracing era, and part of the promise was a new sonic engine that would open up a new frontier for ongoing development. That in turn has led to C-Class bracing for the GT guitars. Do you feel as though V-Class is living up to your expectations?

We’ve certainly been enjoying the development opportunities V-Class is allowing. I was thrilled to get to implement the asymmetrical C-Class on the GT guitars, and there are future developments in that regard. With the V-Class guitars themselves, there are different ways that they can be tuned. Even among different models where we use similar woods, we’ve gone so far as to create different voicings for back braces just based on the model. You’ll hear these different colors come out based on how they get used. For example, if you look at the back braces on a maple Builder’s Edition 652ce 12-string, it’s a very different profile than our other maple guitars — the way the brace tips finish, the way they’re positioned, are different to fit the voicing of that guitar.

You’ve also expanded Taylor’s sonic palette with new body styles like the Grand Pacific. As those and more GT model offerings get into the hands of players, it feels like we’re seeing a noticeable broadening of the line’s appeal beyond our flagship Grand Auditorium, which, for a long time was synonymous with what people considered the signature Taylor sound.

Yes, there’s some truth in that. People are known by their body of work, and that’s the case whether you’re a guitar maker, a musician or an artist of a different medium. It’s very easy to become accustomed to a certain style when that becomes most of what you do. It’s similar to listening to a favorite band — you get used to their sounds, their songs and style. Then they produce a new record that’s very different, and you can hear that this is the same band, but they’ve evolved, they’ve developed some more flavors, more sounds. As a guitar manufacturer, sure, lots of people think of us as the Grand Auditorium company. We build the quintessential modern acoustic guitar, which is a GA with a cutaway. And we love those guitars. They fit perfectly in a big swath of what a musician wants to do with an acoustic guitar. But it’s not the only thing that should exist. As company, we started with jumbo guitars and dreadnoughts before creating the Grand Concert. We’ve created the GS and GS Mini guitars. And more recently, the Grand Pacific and Grand Theater guitars. I really like how the GP and GT guitars are working for players. It’s great to see all of these varieties fall into place within different musical settings. I like all of those flavors.

With our annual Wood&Steel guitar guide, we tend to deconstruct our guitars and explain the tonal characteristics associated with key components like body shapes and tonewoods. Last year, you helped us create visual tone charts for different woods, and what you identified were four categories that help create a tone profile for each wood [frequency range, overtone profile, reflectivity (player/design-reflective vs. wood-reflective) and touch sensitivity]. But the truth is that a guitar is a more complex system of components. So in a sense, a more accurate approach would be to create that chart for each model because it would be more broadly reflective of those elements working together.

The reality is that when you pick up a guitar and you pluck a note, it’s difficult to tell what you’re hearing. Are you hearing the string? The pick? The saddle, the bridge, the top, the back, the neck, the bracing inside, the size, the air mass inside that thing? The sound is not solely any one of those aspects, and I struggle to even apply a percentage of a guitar’s sound that comes from one component versus another. I know that we want to deconstruct things to better understand them because we love them, and every enthusiast wants to understand their guitar better. I think that’s great. But ultimately, what you hear is a composite of all of its elements.

Including the player.

Absolutely. I was recently reading a book by an engineer who was recording Elton John in the early ’70s, and at the time everyone wanted Elton’s piano sound. The engineer used some mike placement and other techniques to try to replicate Elton’s sound, but it still sounded like the studio’s piano. Then Elton arrived for the session and started playing, and it sounded just like him. It wasn’t about the piano — that was just delivering his touch. It’s rather remarkable because a piano has mechanical links between the string and the musician’s fingertips. There are a whole bunch of contraptions to get the motion of one key down through the hammer covered with felt and hitting the string, and it’s hitting the string in the exact same spot every time. It makes me wonder about the way you could touch keys that allows nuance to be heard even through this complex mousetrap of little wooden/felt/leather mechanisms that eventually hits a string, which radically changes the outcome. Now put that into the context of a guitar, where the musician’s fingertips are directly touching the strings, and it’s no wonder the guitar feels like such a personal instrument. It sounds like the person who picked it up.

Let’s set tonal characteristics aside for a moment. You’ve talked about feel and response, which are related to sound but a little bit different.

There are differences here beyond sonority, because we’re not talking solely about what you’re hearing, but what the guitar makes you feel. In turn, this isn’t even directly speaking to how far the strings are from the fretboard, their tension or scale length — setup qualities that are measurable. It’s about the back-and-forth communication you experience when you’re playing a certain guitar. When you pick up a guitar and there’s something about the combination of the sound that comes out of it, the feel of those strings under your fingertips, the resiliency and flexibility, the touch sensitivity — the combination of all the tactile elements and the resulting sound that comes from them — that informs how a player interacts with the guitar.

A player should never feel overwhelmed by choices. Varieties are simply there to enjoy exploring when a musician wants to.

I’ve been playing a lot of different kinds of instruments lately, and this dynamic conversation becomes very apparent. When I pick up an archtop guitar, it has a certain response and pulls me in a different direction in how I’ll play. I notice I have a different touch on a guitar like that than another. When I pick up a GT, there’s something about the slinkiness of the strings and the quickness of its response that makes me phrase even the same melody differently. I’ll inflect it differently; I’ll articulate the string in a different way. If I pick up a Grand Pacific or Grand Orchestra, I might play the same thing, but my touch won’t be the same. It’ll have changed based on what I’m hearing come out of the guitar. Many musicians will use this player/instrument interaction to their benefit and deliberately choose an instrument in order to lead their own playing in a certain direction. Occasionally, they’ll even choose what might be an atypical instrument over their comfortably familiar one to force themselves in an entirely different creative direction.

Can we camp on strings for a minute? In your more recent guitar designs, you’ve started to diversify your string choices a little more with D’Addario strings on the American Dream guitars. Strings are an important element of an acoustic guitar’s feel and sound, and it also speaks to a player’s preferences. Can you talk more about the impact of different strings on feel and sound?

Continuing the idea of an instrument as a system that informs the player and their performance, this dynamic relationship between the instrument and the player interfaces through the touch points of a guitar. I often draw a comparison to surfboards. Each surfboard inherently has a different thing it wants to do, a way it wants to be ridden, and will work best in certain conditions. Beyond this inherent personality, you can tune them by altering smaller characteristics, which can augment their function in unique ways. Guitars are like this. First, what does the guitar itself inherently do? The next important thing is what strings you put on. If a friend tells me they have a new guitar, my first question is, “Which guitar did you get?” followed quickly by, “What strings did you put on it?” My third question would be, “What pick are you using, if you’re using one?” It usually comes in that order because surely the guitar matters — that tells you what you’re working with — and you’re going to decide how to refine that sound with what strings you put on it. The choices are not just about coated or uncoated strings; the choices are what alloy is used for the wrap wire, and what tension range are they? What composition are the strings? Are these phosphor bronze? Is it the nickel-laced bronze like what we’re using on our new AD27e Flametop? Every one of those variables emphasizes a different spectrum, a different kind of response, a different kind of sound that’s being fed into a mechanical system. Moving to the pick, if a player is using one, it’s fun to consider what influence it has in the equation. There are a myriad of variables to play with in terms of the pick’s hardness, shape and surface texture when it rolls off the strings. Despite the numerous parameters to consider, a player should never feel overwhelmed or intimidated by the choices. Varieties are simply there to enjoy exploring when a musician wants to.

For us as a manufacturer, there are often other considerations with string choice, including having the guitars sound and perform well in variety of a retail environments around the world, right?

Yes, absolutely. In a way, this is similar to what a car manufacturer goes through when they build a car or truck. They’ll want it to perform well throughout its break-in period to ensure a long, healthy lifespan and good performance. To help the process, they might select a certain engine oil with additives, or specific tires. In our case, when we build and string up a guitar, we don’t really know if the first musician or tenth musician is the person who will ultimately take it home. We don’t know if it’ll be sold a mile from our factory at a local music shop or if it’ll go halfway around the world on a ship before it finally gets to a music store. Knowing that, we want to use a string that will hold up to all those potentially adverse circumstances and have a nice neutral response for a player to audition that guitar. Beyond that initial break-in period, there are a lot of good, musically interesting options. With some of my own guitars, I use uncoated strings because I like the texture of the string; I like the way it feels. It’s very familiar. It means I have to change strings pretty often if I don’t want it to have a duller sound, but even there, for the right context, I like a duller sound.

As an example, I’ve got an old bass that I’ve played on many recordings, and I use what’s known as a half-round string on it. It’s not flat-wound or ribbon-wound like a jazz guitar string; it’s not a round-wound like an acoustic or electric guitar string; it’s halfway between the two. Fresh out of the package, it has a dusty, somewhat dull sound. On that one particular bass, I love the sound. It works just right for that instrument.

What does a duller string do for how you play it — this might relate to the new AD27e Flametop — and how does it change the way someone might play?

Mechanically speaking, some strings will dampen out a percentage of the high-frequency overtones, giving the audible result of less metallic “zing.” A recording engineer would say it doesn’t have as much sibilance, transient attack or presence. The high-pitch harmonic content gives definition to a note, creating a clear, audible edge to the beginning and end of the note. When this is tempered, the musician will hear a softer, smoother beginning and end of each sound. It’s as if you were hearing more wood and less metal. This warmth will draw a player in a very different direction in how they articulate the strings.

What informs the designs you choose to pursue? I’m sure you’re inspired and influenced by many things. You live a musical life, you have many artist friends you play music with, and you’re attuned to what’s happening out in the music world… but how do you assimilate that input with your own ideas in a way that translates into a design that moves forward?

Design decisions are multifaceted, because part of making anything is discovering what materials you get to work with. It’s rare that any maker says, “I want to build this design, and now I’ll simply go find the perfect material to work with.” Some design decisions are as pragmatic as working with the materials you have on hand or a supply of material that’s reliable and healthy. All the while, I’ll have stewing in the back of my mind different sounds or musical applications I’ve heard or appreciated. I might be thinking of a group of musicians that have been making certain sounds and are inching toward a unique feeling, emotion or playing style that would warrant a good use of a material. Then I’ll think about what complements that: the right guitar shape for this wood and musical purpose, the right voicing, the right finish to put on it, the right strings to put on it. It becomes a recipe unto itself. It’s similar to the way a chef might find some unique ingredient and ask themselves, “What interesting, good thing should we make from this?”

Speaking of available ingredients, I wanted to touch on our use of urban woods, and our desire to operate in a more responsible, ethical way. We want to source materials that will be available to us. Urban Ash has been one. Are you eager to continue venturing down this path?

The urban forestry endeavor remains an exciting adventure for us. When we started working with urban woods, it was one of those projects we pursued because we knew we should, even though it’s surprisingly expensive to do initially, and it seemed like it might not be entirely viable. Despite the obstacles, it seemed like it should be done, and somebody has to start. In the years since we’ve started working with these woods, the concept has turned out to be a lot more fruitful than I had first expected in terms of the quality of the materials we could get and the benefits this forestry model could offer for best use-case of the timber and reducing the pressure on other woods. It’s wonderful to start easing some of the pressure off one material or supply by augmenting our wood portfolio with additional species, with some now coming from urban forests. That means this initiative has a chance to continue at a healthy and steady pace, and we can continue to diversify. That’s a healthy and exciting position to be in as a guitar maker.