I have a 2019 814ce with a cedar top that I purchased from Wildwood Guitars in August of 2019. It’s been lovingly played nearly every day since, and otherwise stored in its hardshell case with an Oasis humidifier. I also have a small digital hygrometer in the case and check it each time I get my guitar out to play. It’s always between 40 and 45 percent RH. Lately I have begun to notice “witness lines” of the [V-Class] bracing pattern in the top. I can clearly see the “V” radiating down from the bridge to the tail of the guitar, and I can also see witness lines of those same braces between the bridge and the soundhole. Is this normal? I love my guitar, and I just want to be sure I am doing everything I can so it has a long and wonderful life. Read Answer

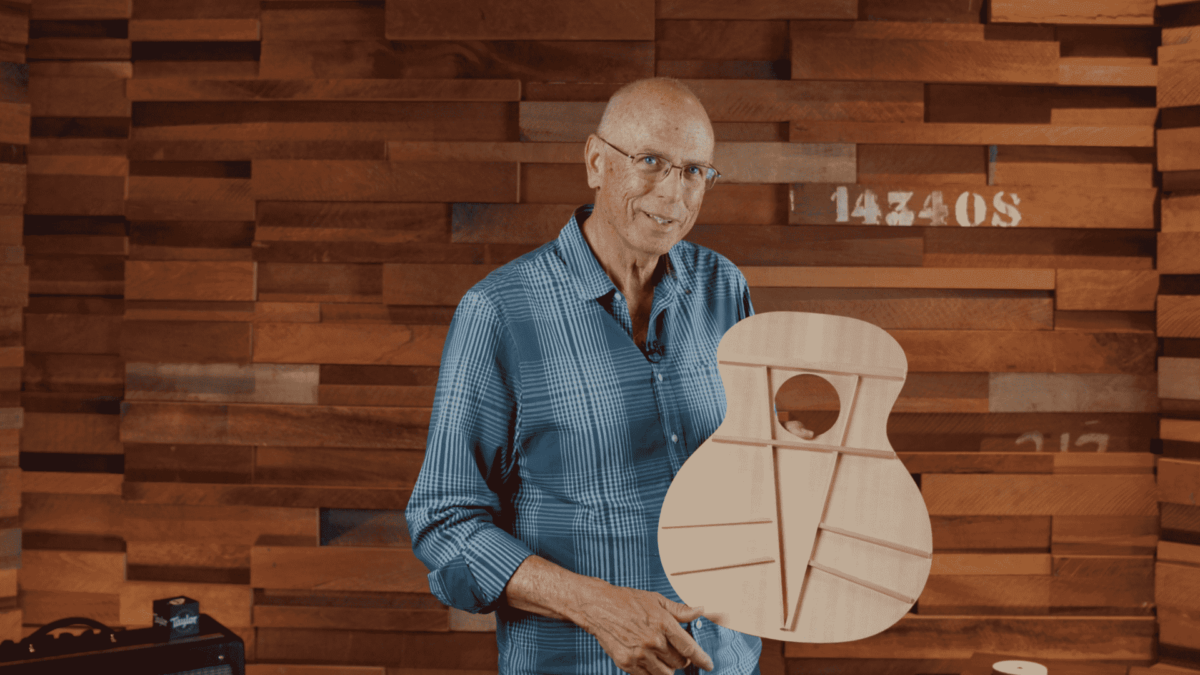

Mike, this is normal and not a problem. Telegraphing is when you can see the pattern of the braces underneath the top by looking at the top in certain light conditions. I’ll try to explain in words, but I’m making a video response as well. Our V-Class bracing is still new to the market after just a couple years, but we made guitars with it in our factory and put them through both our torture chambers and time trials for five years before ever releasing them to be sure they would be resilient. What is so good about V-Class is that the braces don’t run across the top from one side to the other like X bracing does. This helps both the sound and the stability of the guitar. Many other stringed instruments are actually braced in a similar way to V-Class, like mandolins, violins, archtop guitars and others. We have a soundhole in the middle of the top, so we run our braces in the V pattern to pass by the sides of the soundhole. The top of the guitar will shrink and swell with changing humidity levels, as always. An X brace runs across the grain from side to side, so it doesn’t show as much of the telegraphing pattern. But it causes the top to arch up with humidity and down with dryness. This is forever a problem because the string height goes up and down like a bladder being inflated and deflated. Since V-Class runs at only a slight angle in relation to the top grain, as the top stretches from drying, or gathers in on itself as it swells from higher humidity, it does not cause the top to rise and fall. Action and string height stay amazingly stable. This is a huge advantage of the V-Class design in addition to the tonal and intonation advantages. But the top can show the braces underneath when a top stretches or gathers from changing width. It’s just visual. There is no harm being done. It can come and go with humidity changes. Don’t be alarmed. We’ve tortured these guitars to extremes you cannot imagine. We are confident in them.

Are there any urban tonewoods other than ash on the horizon for Taylor? Read Answer

Yes, Pat. We’re looking at eucalyptus and blackwood. And maybe more in the future. There are some great tonewoods out there in the urban environment, most traditionally discarded when a city decides to take them. By the way, we buy a lot of our mahogany from India, as it was basically planted as an urban tree during the colonial years. So without the marketing, a lot of our mahogany sides and backs are actually urban wood. And you should know that most Indian rosewood comes from being planted as shade and/or wind-blocking trees for tea plantations. It’s neat to think that so much is renewable that way.

Bob, much has been written about Taylor’s innovations in guitar design and production, but I’m curious whether your team also has pursued advances in your methods of drying and conditioning your wood. Are there particular challenges you face now that you didn’t have to contend with in the past? Read Answer

Yes, Marc, we are always advancing that process. In fact, as I write, we’re conducting drying experiments to improve the current processes, and this practice never ceases, as it’s one of my dearest interests. We prefer to dry all our wood here on-site. We have very little wood that comes to us dry and ready to use. We have a huge drying operation with dependable methods we’ve developed over time. One challenge we have that we’re working on now is how to make wood more stable through drying, re-drying, and even some heat here and there in order to be able to expand more easily in the high-humidity equatorial regions of the world. We have such high demand for our guitars, so this keeps us on our toes. Here where we live in Southern California, it’s about keeping the guitar from cracking in dry conditions. But there it’s about keeping it from swelling from ultra-high daily humidity. We never stop trying to improve this. It’s a core competency of ours that is foundational to a good guitar and our business.

What is the drying time for different tonewoods before they can start to be machined for tops and sides? Do some woods process sooner than others, and how is tone affected? Read Answer

Al, I’ll start by saying that we dry for stability more than tone. If we do a good job of that, the tone is the best it can be. Wood with lower moisture content always sounds better since water weight adds nothing to tone. So we work toward stability, and that means removing water in ways that make it difficult for it to re-enter the wood. Nearly all of our woods can be dried in a two-to-three-month, highly controlled process. But since we carry more wood stock than a few months’ worth, we usually dry it longer since it’s there anyway.

Can you explain the theory behind your angled back bracing? Read Answer

Alexa, in the time I’ve spent with Andy Powers, he’s taught me much of his knowledge of guitar making. He’s quite clever and thinks of things most of us mere mortals don’t! Let’s start with the fact that, back in the day, I started making acoustic guitars with bodies that were less deep than other guitars. That makes them comfy to hold and play and gives them a clarity of tone that has great utility. Andy recognized both of those assets, and when thinking as he does about how to solve an acoustic problem with a guitar in an unconventional way, he fashioned the idea of making the braces at an angle. This makes the back asymmetrical and controls its tension in a way that Andy knew would enhance the low-end response but not add what could be described as a reverb response, which sort of undoes the clarity virtues we like in the guitar I made and Andy inherited. So this did the trick. If you just think of how differently the angled braces spread the load, the tension and the vibration over the back compared to if it were broken into equal quadrants like normal back braces, you can get an idea that it’s really different acoustically. I asked Andy today if he would do that to a more traditional-depth guitar too, and he said while he thought of it as a solution to a shallower guitar, that yes, he’d do it now to a deeper guitar if that guitar was in need of what this offers. I love learning from Andy!

Is the ebony wood [processed] in Cameroon by Crelicam exclusively Gabon ebony? Are royal ebony and Macassar ebony different species than Gabon? Are there other species of ebony besides those three that are commonly used for parts of guitars?

At a Road Show before the quarantine (at Music 6000 in Olympia, Washington), I was able to play an E14ce [featuring ebony back and sides]. I love the sound of that guitar — I felt that it presented a strong and solid fundamental. There was some gradual overtone bloom (which I do appreciate), but I found the way that the full chords initially hit me very satisfying. Is it reasonable to assume that the beautiful back and sides of that guitar came from the Crelicam mill? Are the folks in Cameroon selecting which logs become fretboards and bridges and which ones might be good choices for backs and sides? Or are those decisions made in smaller chunks than the whole log? Read Answer

Robert, that’s a lot of questions! Okay, Gabon ebony is the same as Cameroon ebony. Look at your smart phone map and notice that Gabon is the country sharing part of the southern border of Cameroon. The species is Diospyros crassiflora Hiern, and the tree isn’t aware of the border. Macassar ebony, on the other hand, comes from Indonesia and is Diospyros celebica. And Madagascar ebony is Diospyros ebenum. FYI, persimmon fruit comes from Diospyros kaki. And there are many other Diospyros species, too, spread out across the tropics. The blackest comes from Madagascar. Macassar is different and is highly colored. Cameroonian ebony that we get from our Crelicam mill is both black and colored. Currently, more trees are colored from that region. We do not extract whole logs since we don’t have roads that offer access to the trees. We use big four-wheel-drive trucks, on a machete-cut path into thick forest to extract the blocks we cut on-site. These are usually 500-pound blocks. Then, reading the color of those blocks, we will direct the wood to the best value part to make. The colored pieces are called royal ebony, as you referred to it, by some people, but we don’t use that term — although I like the ring of that name! Thank you for the comments on the tone. Your description might help others, so I appreciate the descriptive wording.

I am the proud owner of a 514ce made in 2018. I am still amazed at the sweet sounds I get from my guitar’s cedar top. I can hear nice ringing tones from the B & E strings when I fingerpick. I wanted to find out more about the selection process for cedar tops. I have played spruce-top guitars for a long time, and I know that wood is ubiquitous in acoustic guitar building. How do you know which cedar logs will work for the tops you put on the 514? Read Answer

It’s easy, Anthony. We just look at it. It’s that simple, but straight grain, no structural flaws, and accurate quartersawn cutting from the mill all add up to cedar you can depend on. We don’t over-use cedar because it’s hard to work with compared to spruce, so there’s a limit to how many guitars we can make. For instance, it takes forever for glue to dry on cedar. I’m often asked how we know something will sound good. There’s no mystery to it for us. It’s like asking a chef how he or she knows something will taste good. In the same way, if I suggested you put ketchup and mustard on your morning granola, you’d know that is just wrong, as wrong as can be, even if you’ve never tasted it. Well, the tonal properties of wood are like that for us. We touch it, feel it, smell it, tap it. Then we know.

I know that humidity is a concern for guitars, and the recommendations are usually given in relative humidity terms. Isn’t specific humidity most important? I live in the Pacific Northwest, and while our relative humidity is high, the temperatures are cool, so our specific humidity is low. A tropical climate might have a relative humidity in the recommended range, yet have a high specific humidity. Which is better? Read Answer

Good question, M! Some refer to that as absolute humidity. If we were making Gummy Bears or shiny chocolate bars, absolute humidity, so I have heard, is important. Without getting geeky, which is hard not to do, relative humidity (RH) is the amount of water in the air relative to the air temperature’s ability to hold water. So when the RH is 50%, it means that at that given temperature, the air is at 50% capacity of what it’s capable of holding. Raise the temperature and then it can hold more, so it changes to 40% or 20%, depending on the temperature rise. Lower the temperature and the RH increases, since cold air holds less water. Absolute humidity is how much water is in a volume of air, regardless of the temperature.

Okay, here’s the answer. Wood equalizes to the relative humidity, not the absolute. So does your bath towel or your potato chips. This is called EMC (equilibrium moisture content), and the wood will gain or lose moisture in an effort to equalize to the surrounding relative humidity. A bath towel tends to stay damp in a Seattle house and get really dry in a Las Vegas house. So does a guitar. The absolute humidity works differently. At Taylor, we prepare our wood and build at close to 50% RH, which is a good all-around level to build, and the guitar is very happy if it gets to experience that out in its working life. It can withstand changes, but it’s nice if it experiences that and not the extremes.

As an amateur builder, I have made about a dozen guitars. Without the money to invest in top-quality specialized tools, I’ve always resorted to trying to figure out how to make certain cuts or make bends in different ways, or use different materials and techniques…some obviously more successful than others. My questions have to do with why other stringed instruments like violins and cellos have a sound post but guitars do not. And why not also make the back out of the soundboard material? Wouldn’t more movement produce more sound? Read Answer

Rick, with a violin, a sound post is meant to excite the back to vibrate with the top. Remember, it’s a bowed instrument, and the power going into the string is enormous — many, many times greater than a pluck on a guitar. And so that constant bowing motion can get the violin to really perform! It’s so loud. It’s wonderful. The guitar is a different thing. So now think of what a violin sounds like when it’s plucked. Boink. It’s kind of a letdown, isn’t it? It takes 10 of them in the orchestra to even hear that measly pluck. No sustain at all. None. Sound over. The guitar’s soundboard resonates and sustains. The back is there to support it, add some color, and fill out the tone in ways we can alter as I explained in the question regarding back bracing. The body is a sound box almost like a speaker cabinet. It’s just different for a different purpose. So a spruce back doesn’t add much. Something hard that still moves gives us the tone we want for the back. And a sound post would stop the top from vibrating and turn it into a boink.

As an owner of two Taylors — a 2004 W12ce and a 1984 712 (Lemon Grove) — and always looking to add to the collection, I pause because of the use of ivoroid, Italian acrylic and tortoise (fancy names for plastic) for binding and inlays and basic plastic pickguards. I am curious why Taylor would “gild the lily” with plastic, especially when Taylor does everything else so flawlessly and because many other makers (at comparable price points) are binding with flame maple or ebony or a variety of woods. And fret inlays, etc., are abalone, mother-of-pearl or wood.

As for pickguards, as a fingerpicker, for me, the pickguard adds nothing to the instrument. Can they be removed, or, better yet, can Taylor send them with the instrument and let the end user install or not? I see you use some wood pickguards, and they appeal much more than plastic. But all this plastic limits my Taylor options.

With an instrument as smartly designed and produced as yours, why “pollute” all that wood and steel with plastic? Read Answer

John, ivoroid and tortoise are not just plastic, they’re nitrocellulose plastic, the original plastic. What film is made of. It’s not made in the U.S. anymore because it’s so volatile in the manufacturing process. It’s made in Italy and has deep, deep roots in the history of guitar making. Italian acrylic is similar — made in Italy like the others to be beautiful and preserve some tradition. It’s not made here, there’s no profit in it for American thinking, so “grazie mille” to the Italians. We make a lot of guitars. Hundreds each day. And I think when it comes to guitars made in El Cajon, we actually make more wood-bound guitars than anyone anywhere. So I guess we have a different viewpoint. As for your pickguard question, we produce some models without them. And we like the wooden ones we make for certain series. Again, plastic is pretty traditional. Putting it on yourself (maybe not you personally) would likely be a disaster. It’s not easy to position it exactly where it belongs on the first try. We have the tools and skill to do that here in the factory.