Bob Taylor is sitting in his office, mentally sifting through a half-century of Taylor inlay design history, stretching back to his earliest days as a teenage luthier. At one point the conversation turns to the company’s most recognized inlay of all — the peghead logo that graces every Taylor made. The original version was inspired by the logo for a thermometer that hung in the shop in Lemon Grove, California, where the company started in 1974.

“I cut hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of those inlays with a saw and a file,” he says, walking to a whiteboard on the wall. “I used to draw those, starting here at the bottom left,” and proceeds to draw the entire outline of the logo from memory, even though he hasn’t cut the inlay in decades. “It’s so impressed in my mind, I can start in that corner and go all the way around. I could almost close my eyes.”

Inlay design for guitars is a rich topic of conversation — an art form all its own, literally embedded within the art form of guitar making. Though the aesthetic approach can be beautifully minimalist, letting a guitar’s refined contours and tonewoods speak for themselves, most stories built around an “art of the inlay” theme inherently skew toward images of highly pictorial, narrative or ultra-personalized artwork that showcases singular inlay craftsmanship. If you appreciate that type of artistry, you’re probably familiar with the work of inlay maestros like Grit Laskin, Harvey Leach or Larry Robinson, or maybe the late Larry Sifel or Wendy Larrivée.

“I remember watching Wendy engrave one of her court jesters from her blocks of pearl many years ago,” Bob says, marveling at her skills. “That kind of work has become something of a lost art.”

In Taylor’s case, trying to highlight 50 years of our inlay design in one article is, of course, a tall order, deserving of a hefty coffee table book. Beyond the sheer volume of inlays Taylor has created over the years, there are multiple storylines worth exploring. There is the evolution of our craftsmanship methods, which have progressed from Bob’s early days of hand-cutting pearl with a jeweler’s saw to the integration of CAD/CAM, CNC and laser technology into our current product development efforts. There are the aesthetic sensibilities that have taken form and been refined here at Taylor, along with styles that have changed with the times or by strategic choice. And there are the people who have brought their unique artistic points of view and skill sets to Taylor’s design team over the years, from Bob in tandem with his longtime creative partner, Larry Breedlove, to talented designer Pete Davies Jr., who created some of Taylor’s most visually striking inlays, to our current guitar architect, Andy Powers, whose thoughtful visual details create a harmonious marriage between a guitar’s musical personality and its aesthetic features.

A Rich History of Inlay Art

To put Taylor’s approach to inlay design in perspective, it might help to provide a bit of context about the history of inlay art in the musical instrument world. The heritage of inlay art for steel-string acoustic guitars reflects a fascinating cross-pollination of different musical instrument traditions stretching back half a millennium. Through the centuries, the violin world experienced different ebbs and flows of ornamentation. During the Baroque period, for example, violins often featured extensive decorative details, but over time, that approach was heavily distilled so that inlays were typically not featured on a fingerboard. Instead, luthiers would focus on specific appointments like inlaid purfling.

“Purfling and edge treatment became the place where a maker would show their abilities,” says Taylor master guitar designer Andy Powers. “It became an exercise in how perfectly executed the purfling was, and the artistic flair of how you cut and fit the parts — the size, the proportion, the look of the joints between the pieces.”

With guitars, if you trace their development back to the tradition of lutes or ouds, you’ll see examples of heavily ornamented instruments. But instruments were also made with modest appointments for the folk musicians of each era.

Classical guitar makers took a page from the violin world and left the fingerboard unadorned, similarly focusing their inlay artistry on creating attractive purflings, while also crafting beautifully intricate rosette mosaics to demonstrate their refined skills.

In the U.S., banjo makers, especially those of the American Dixieland jazz era of the 1920s, adopted a more flamboyant approach to ornamentation, often with elaborate inlays, including in the fingerboard. That aesthetic would soon be embraced by steel-string acoustic guitar makers as a way of attracting banjo players. Companies at the forefront of that tradition included Gibson and Epiphone, which were building both banjos and guitars.

“Look at an early Gibson banjo or mandolin that was elaborately inlaid, and it’s easy to see there wasn’t a big step to start putting those inlay treatments on a guitar,” Andy says. “These inlays were done on flattop guitars to a certain degree, but both Gibson and Epiphone were heavily invested in building archtop guitars, which were more widely used by musicians crossing over from the banjo. Often, these guitars carried then-popular Art Deco visual themes, adopting the vibrant, flashy aesthetic of the Jazz Age. This desire for visual prominence was thought to further emphasize the guitar’s growing importance in a band.”

Taylor’s Inlay History

Back in Taylor’s earliest days in the mid-’70s, Bob Taylor says, adding inlays to a guitar was rewarding on two levels: It was a way for him to hone his chops as a young woodworking craftsman and to get a little more money for a guitar so the company could pay the rent.

“I could add an ab [abalone-edged] top and some other inlays to fancy up a guitar and turn a $600 guitar into a $900 guitar,” Bob says.

One of Bob’s early artistic influences with inlay design was banjo maker Greg Deering, whom Bob had met at the American Dream guitar shop where he got his start and Deering was working as a repairman. Deering would later work as a repairman in the early days of Taylor Guitars for a short time before founding Deering Banjos.

“I think my lucky strike was that Greg worked in the shop and then had a shop behind me,” Bob says, “because Greg is a fabulous inlay designer.”

Many of Bob’s early inlay ideas were inspired either by visual elements he saw in everyday life — such as a piece of Mexican tile, he says — or other traditional designs that tend to work well with guitars, like leaf, vine or other botanical themes.

“With this leaf sort of an idea, if you engrave it, it can look really good, and if you don’t, you’d work on the cuts,” he says. “In the early days when we would hand-saw, you could make deep cuts into the leaves. But when we first started doing CNC [cutting] work, initially we couldn’t do that anymore because they didn’t really have super good cutters for that sort of thing — they were pretty big in diameter, so you lost a lot of detail. But then cutters started getting better, so you started getting back some of that detail.”

Larry Breedlove Makes His Mark

In 1983, a skilled craftsman and luthier named Larry Breedlove started working at Taylor. His design collaborations with Bob over the next three decades would define the elegant aesthetic that people now intrinsically associate with Taylor guitars — from the supple curves of Taylor’s family of body styles to the shape of our iconic bridge to so many of Taylor’s inlays. Breedlove brought a uniquely organic, architectural and sculptural sensibility to the guitar form. His love of wood and innovative furniture design informed his aesthetic approach to acoustic guitar design.

“Larry was like a modern furniture builder,” Bob says. “He built furniture a little more angular but more in the vein of a Sam Maloof rocking chair,” Bob says. “His stuff was kind of organic like Gaudi, but it didn’t look like a branch. It was more sculpted and refined, somewhere between organic and mechanical. His shapes and ideas for form were really nice. And that aesthetic worked well for the types of inlays that we did. So we kind of modernized some of the old banjo inlays.”

Breedlove also took on a lot of the custom inlay design work that had started with Taylor’s Artist Series in the mid-1980s (including some envelope-pushing color finishes on guitars for the likes of Prince, Kenny Loggins and Jeff Cook from the band Alabama). Along the way, Breedlove started working with alternative inlay materials to expand his color palette.

New Tools, New Inlay Designs

The 1990s would prove to be a transformative decade for Taylor Guitars in many ways. For starters, acoustic guitars experienced a resurgence in popularity after a decade of commercial dormancy, thanks in part to the cable television show MTV Unplugged. After a decade dominated by synthesizers, electronic drums and hair metal, acoustic guitars became cool again, as rock acts stripped some of their hits down to intimate acoustic performances. And many rockers were happy to discover that the slim neck profile and easy playability of a Taylor neck felt similar to electric guitars. Other emerging artists like the Dave Matthews Band also made the acoustic guitar a centerpiece of their music (and it didn’t hurt that Taylor guitars became a mainstay of Matthews’ live shows in the ’90s and onward).

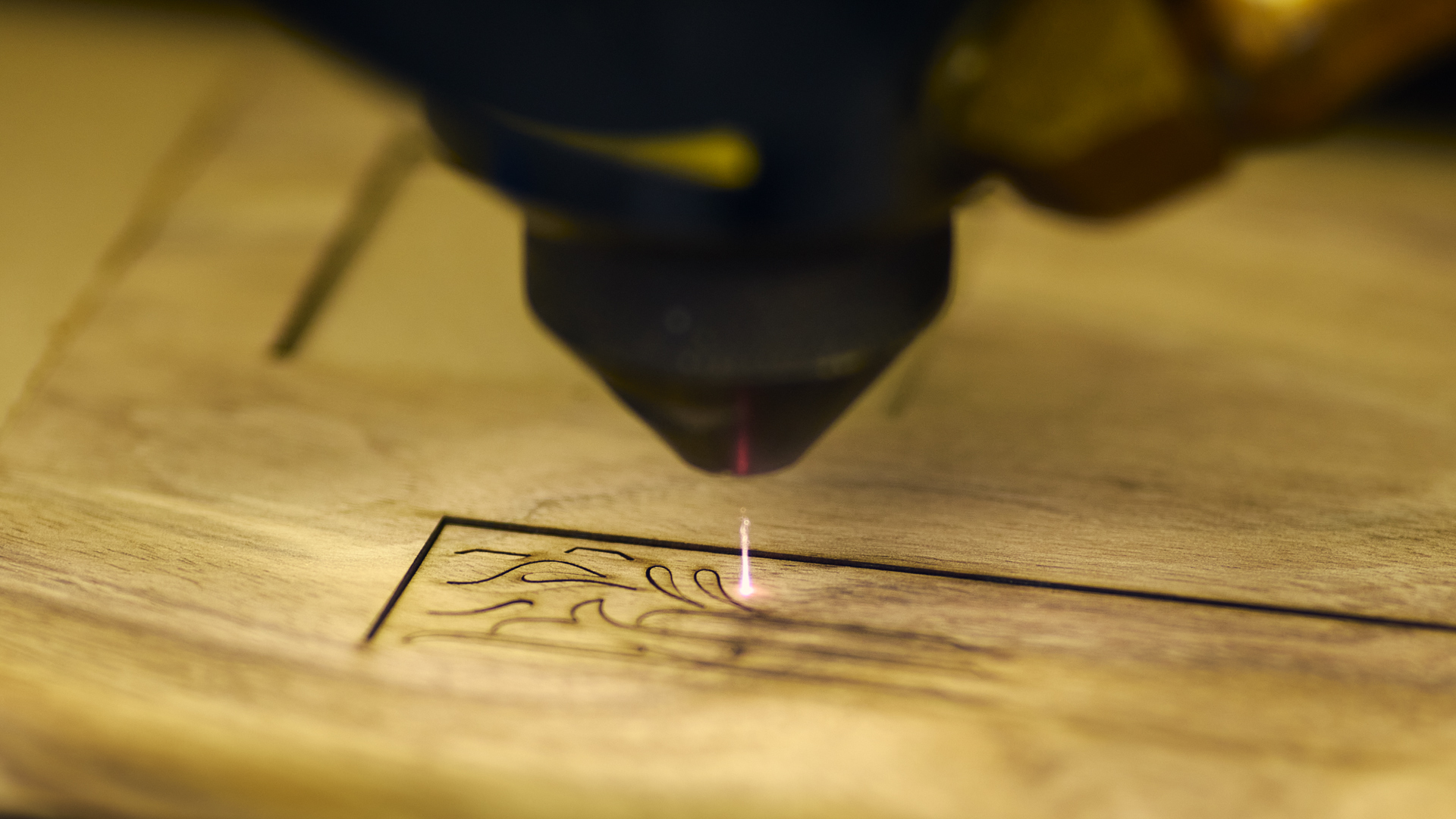

As our guitars were growing in popularity, Taylor was also bringing cutting-edge tools and technologies into the design, product development and manufacturing processes. Computer-controlled mills and laser technology introduced new levels of precision and consistency to guitar production. They also proved to be game-changing tools for inlay creation. Pearl or abalone shell inlays — and the pockets that would house them — could be cut more accurately with a CNC mill.

“With the advent of CNC,” Bob says, “we could design inlays that were a little nicer, a little fancier, for our more expensive guitars. Even if another vendor ended up cutting the inlays for us in some other location, we knew it would fit in the pocket we carved for it on a CNC. It was like ordering a carburetor for your car — you expect it to fit when you open the box and install it. Whereas before that, every inlay was almost like starting over.”

Lasers also opened the door to new inlay materials beyond traditional shell, including different woods and synthetic materials like Formica® ColorCore®. And because of the small diameter of a laser beam (.008 inch) and the accurate registration, lasers could also be used to etch detail into certain inlay materials like wood or acrylic to enhance their look.

In the mid-’90s, with the company hitting its stride, and bolstered by the successful debut of the Grand Auditorium, Taylor decided to put more creative resources into doing custom design and inlay work. By the tail end of the decade, Taylor’s ability to create visually compelling inlays for standard, limited-edition and custom models had grown significantly. And with Taylor actively cultivating relationships with popular artists, the years that followed saw the company embrace these new design tools to create a series of more pictorial-themed inlays for artist signature guitars, along with other visually themed limited-edition models.

One of the most elaborate story-themed inlay designs of that time was for the Cujo guitar (released in 1997), featuring figured walnut back and sides that came from a tree that had been removed from a farm in Northern California. The Cujo tie-in was that the tree appeared in scenes in the film adaptation of the Stephen King novel Cujo (1983), about a St. Bernard bitten by a rabid bat that ends up terrorizing a mother and her son. The inlay portrayed narrative elements of the story, including the dog, the bat, a barn and the walnut tree itself, incorporating a variety of wood, shell and other materials. The consistency of the technology used to create the inlays enabled us to create a run of 250 guitars.

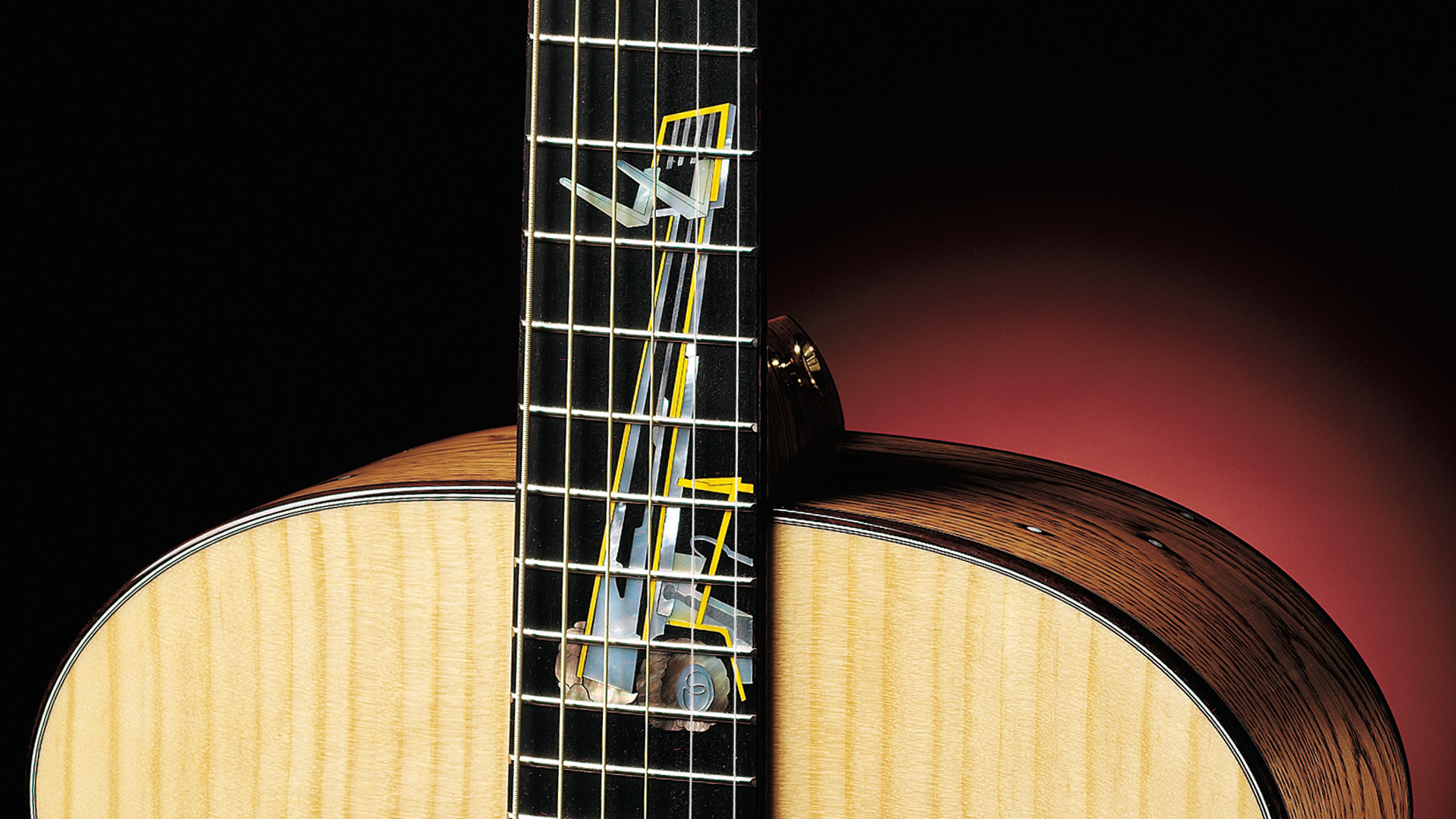

Another key Taylor inlay artist from that period was a young talent named Pete Davies Jr., who arrived at Taylor fresh out of design school in 1999 and brought an inherent knack for creating art that could be translated into visually compelling pictorial inlays. Longtime Taylor fans will recognize his work. His first inlay design was a koi fish inlay for our limited-edition “Living Jewels” Guitar, the first offering of what would become our Gallery Series. Colorful koi fish “swam” along the fretboard and around the soundhole of the figured maple/Sitka spruce guitar body, which had been stained blue to simulate water. For his inlay materials, Davies used synthetics: ColorCore, faux pearl, and a composite of ground turquoise, coral and stone mixed with resin. The guitar was visually stunning, as were the other Gallery Series models created. The Sea Turtle Guitar featured inlaid sea turtles in the fretboard and another turtle with a jellyfish inlaid into the blonde, figured maple back of the guitar body. A third limited edition from the collection, the Gray Whales Guitar, featured whale inlays and a striking rosette featuring a galleon ship that partly extended into the soundhole.

Another intricate inlay designed by Davies adorned the Liberty Tree Guitar, crafted with wood from a 400-year-old tulip poplar tree that served as a gathering place for patriots in Annapolis, Maryland, during the American Revolution in 1776. Davies’ inlay scheme commemorates the tree’s historical significance with a depiction of the first post-revolution version of the American flag in the peghead, a scrolled, laser-etched depiction of the Declaration of Independence that extends from the fretboard onto the soundboard, and a rosette featuring 13 stars (representing each of the original colonies) and a Colonial-era banner that starts on the edge of the fretboard and unfurls across a portion of the rosette. Between the historical significance of the wood and the inlay art that honored it, the guitars were truly special.

Other custom designs originally created by Davies for limited-edition models include a flame inlay for our limited-edition Hot Rod Guitar (HR-LTD), inspired by old hot-rod cars, featuring inlaid flames (in wood) along the fretboard and around the soundhole; a beautiful inlay of horses in maple and koa for our Running Horses Guitar (RH-LTD); and a pelican inlay crafted from koa, walnut, satin wood and myrtle.

After a five-year run, Davies decided to leave the company to continue his career in 2004. (Sadly, he passed away in 2014 at the age of 37.)

A Recommitment to Guitar Design

By the time Pete Davies Jr. left the company, Taylor had gone through a substantial period of growth. The company had also pushed the envelope artistically with a prolific outpouring of custom inlays for artists and a slew of other limited-edition guitar offerings. With Davies gone, Bob Taylor, Larry Breedlove and others on the product development team considered the path ahead and the pros and cons of continuing to invest in this aesthetic approach and operating a robust custom program.

“We had swelled that up, done some business, and it was great for a while, but I started to feel like we were getting stuck in that place,” Bob says. “We tried to make a business of it. There were a couple of people who wanted some really fancy, money-doesn’t-matter guitars. Even with what we charged, we didn’t really end up making money or offering enough value. And the opportunity cost was really high because we’d lose Larry into a custom-design black hole for months at a time.”

“I didn’t want Andy to be known as an inlay king here at Taylor. I wanted him to be known as a person who’s continuing to advance what a guitar can do.”

Bob Taylor

Meanwhile, Taylor continued to innovate with its guitar designs. In 2005, the company introduced the hollowbody electric/acoustic T5. The Grand Symphony body style, designed by Bob and Larry Breedlove, came a year later, followed by other designs that included an 8-string baritone, and in 2010, the GS Mini, also designed by Bob and Larry.

By that time, Bob had been talking to a talented local guitar maker named Andy Powers about joining the company and the role he would play as Taylor’s next-generation guitar designer. Andy signed on and officially started in January of 2011.

“With Andy’s arrival, we made a conscious decision that we were not going to concentrate on highly inlaid, bespoke guitars, where we try and develop a business of making custom guitars through inlay work,” Bob says. “Andy’s an incredible guitar builder, and I was ready for us to renew our focus on the quality of the guitar as a musical instrument rather than a piece of jewelry. So much energy can go toward maintaining the talent and management required to do inlaid works of art. We were in a time when we felt it was appropriate to make elegant inlays for our guitars and largely stay away from the thematics we’ve done in the past.”

One of the ironies, Bob adds, is that in addition to being a superb luthier, Andy is also a gifted inlay artist capable of highly pictorial themes.

“He’d do amazing inlays like tigers walking across the guitar,” he says. “But I didn’t want Andy to be known as an inlay king here at Taylor. I wanted him to be known as a person who’s making better guitars than we made at Taylor before he came, who is continuing to advance what a guitar can do, how long it can last. We both felt like that’s the best value we can offer our customers.”

Andy’s Inlay Epiphany

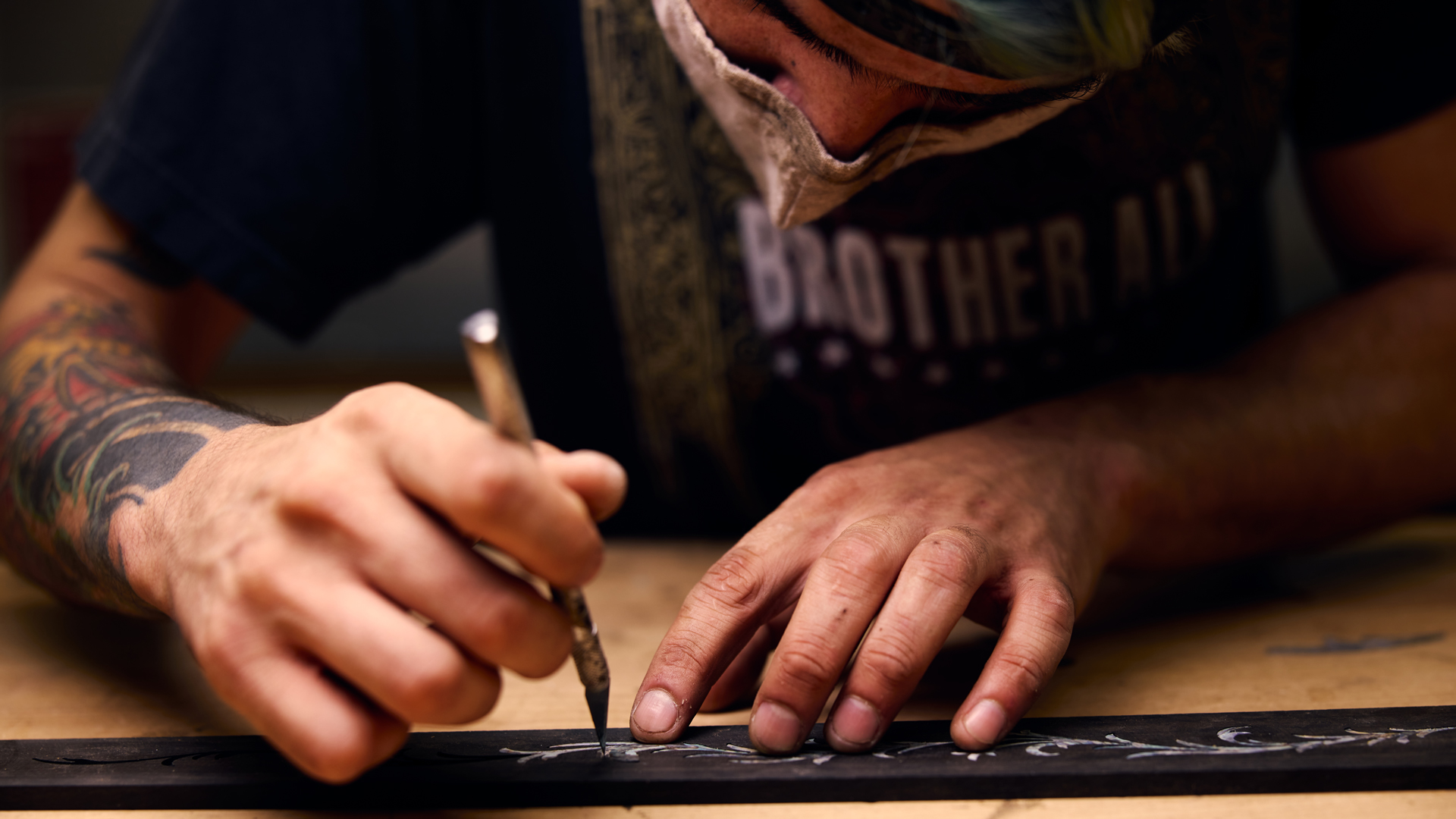

Andy is proud of the custom inlay work he did on the guitars he built before joining Taylor. And for good reason. Not only is his portfolio visually stunning, the work was entirely hand-drawn and hand-cut.

“The tradition of hand-cut inlay work was something I admired and enjoyed a great deal,” he says. “I was working with a jeweler’s saw and some tiny files. I may as well have been working in the 1700s.”

Based on the type of inlay work his customers wanted for their guitars, Andy sees parallels with contemporary tattoo artistry.

“Think about the variety of tattoos a person might get,” he says. “You see anything from the names of their children, depictions of their life stories, inspirations, mottos, beliefs. A lot of people approach inlay art in a similar vein — they want this one instrument to tell their story…some experience, some hardship, some success, some failure. I was pretty into that because I enjoy the human-interest aspect of this work.”

He also enjoyed the artistic challenge of finding a way to graphically depict a person’s story, and working within the constraints of the medium and the materials when done by hand. But Andy started to think differently about his approach to inlays after a visit at his shop from none other than the late Bill Collings from Collings Guitars.

“Any inlay design should offer some indication of what the guitar will feel and sound like.”

Andy Powers

“He was looking at this guitar I was building for a customer,” Andy recalls. “I’d spent weeks working on this very elaborate inlay work, and I was proud of it. Bill turns to me after staring at this guitar and says, ‘This is exceptionally beautiful work. But if I were you, I would start thinking about who will own this guitar after this first player, because musicians are going to want to play this guitar for much longer than you think.’ We stood there in silence for a few minutes while I thought about it, before I responded. ‘So, in other words, you wouldn’t want to have somebody else’s mom’s name tattooed on your arm?’ And he said, ‘Exactly.’”

In the years that have followed, Andy says, that observation has proven to be true, as he watched guitars he built for clients go to their children.

“In one case, the player who ended up with the guitar told me, ‘I love the guitar, but it’s my dad’s story, not necessarily mine.’ That experience made me more interested in the traditional side of inlaid art and focusing on certain themes that are a little more universally appealing. Of course, the classic subjects — botanical motifs, some shapes that are more impressionistic — usually work.”

It reminds Andy of a trip he took to Cremona, Italy, some years ago, where he had an opportunity to see a beautiful Stradivari violin up close.

“It had some heavily ornamented art, which was unusual,” he recalls. “Parts were hand-painted, elements were carved in and filled with contrasting mastic, so it wasn’t necessarily inlaid pieces but had a similar visual effect. It was a botanical kind of motif, and the lines felt as elegant today as they would have been back in the 1700s when it was done. I thought, now that’s a beautiful approach to ornamentation.”

Andy’s Approach to Inlay Design at Taylor

Andy echoes the point made by Bob Taylor that his creative focus at Taylor should be on foundational-level improvements to guitars rather than extreme customization. That said, part of that focus has led to an array of thoughtful new inlay designs within the context of Taylor’s standard guitar line.

Since his arrival at Taylor a decade ago and in his role as master guitar designer, Andy has been on a steady path of transforming virtually the entire Taylor guitar lineup, refining the feel, sound and look of most existing models and introducing many new designs as well. Regardless of the type of guitar, the aesthetic approach, he says, is fundamentally the same: It has to be a holistic design process in which the musical personality and the aesthetic treatment share a cohesive identity.

“If you look at any inlay design, it should offer some indication of what the guitar will feel and sound like,” he explains. “Shapes certainly matter. Materials matter. Visual weighting matters, like how bold or how subdued the visual strength of an inlay is.”

He uses the Grand Concert Builder’s Edition 912ce as an example.

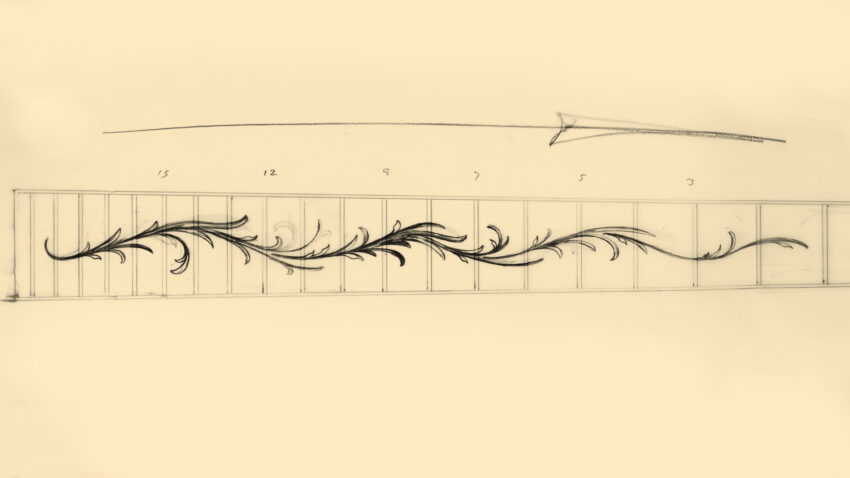

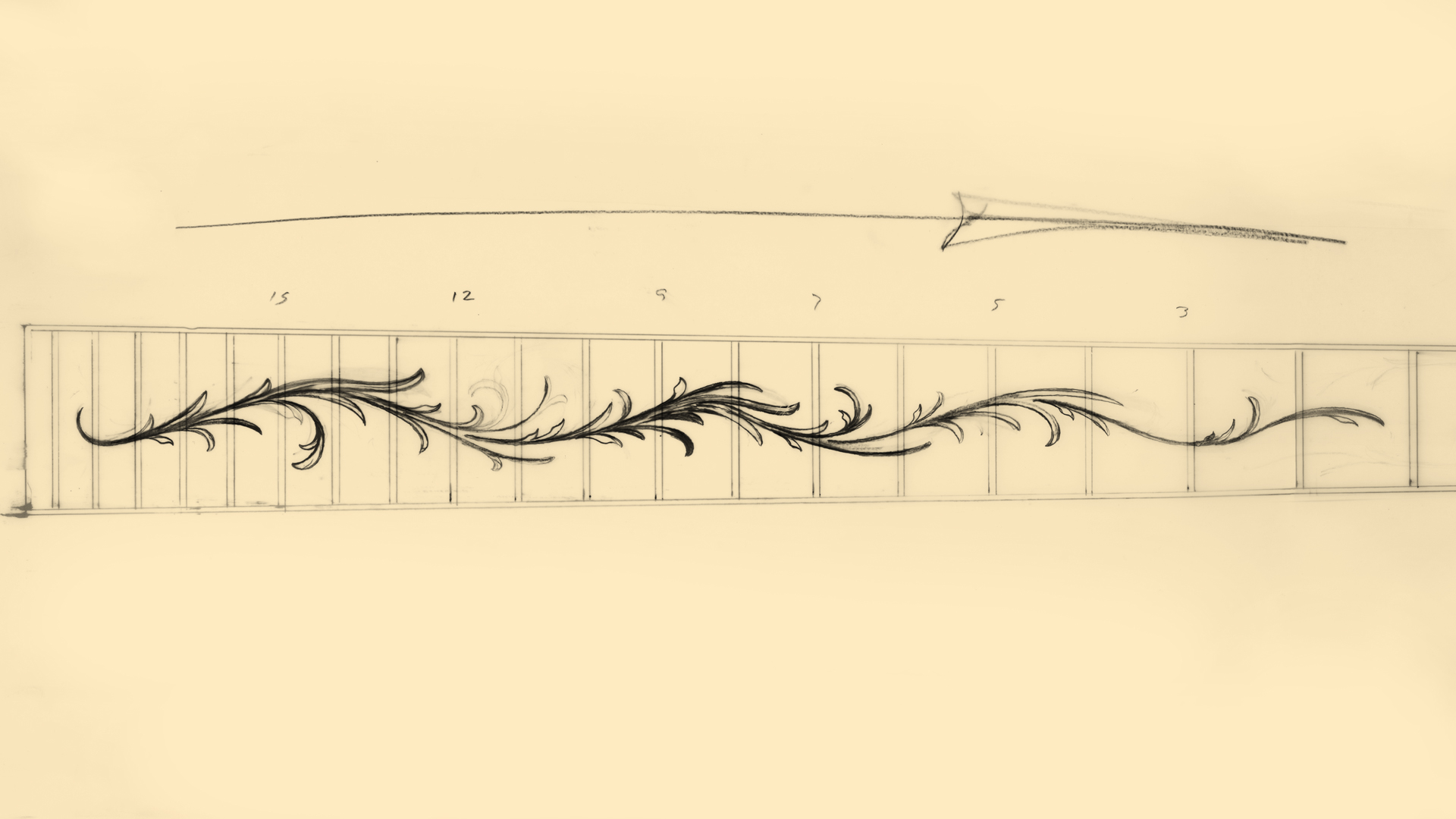

“The smaller body tends to give it a more intimate, elegant feel,” he says. “Now imagine it with big, blocky mother-of-pearl inlays at every position. You’d have this massively shiny, reflective fingerboard, and it would be so visually heavy it would look like the guitar might fall right out of a stand. It wouldn’t be in balance with itself visually. But with the Belle Fleur inlay, there’s a balance of strength and delicacy with a little Art Nouveau, a little Art Deco, a little stylized impressionism in there. I see that and think, it looks like the rest of the guitar. It fits. It doesn’t have any one thing that overpowers something else. The types of curves used suggest the curves of the beveled cutaway and the armrest and the overall silhouette of the guitar. All of those elements go together.”

This inlay design philosophy can sometimes present challenges within the framework of the Taylor line. Each series in the line traditionally has shared a suite of appointments (and in most cases, the same back and side wood), yet different body styles within a series can have very different sonic personalities.

So, at times, Andy has exercised his creative license to design outside those constraints. His Builder’s Edition framework gave him one particular avenue to deviate from a series to create another class of “director’s cut” models. With the debut of the Grand Pacific, for example, Andy chose to craft the Builder’s Edition 517 and 717 with an appointment scheme that reflected the traditional heritage of dreadnought-style guitars and a different musical voicing for Taylor, so the two models shared an aesthetic sensibility and an inlay design with each other rather than with the 500 Series or 700 Series.

Another example (though not a Builder’s Edition design) was the redesign of the Grand Orchestra in 2020 to feature V-Class bracing and a new appointment scheme. The two retooled models, the 618e and 818e, feature a shared inlay, the Mission, which is different from the other inlays used with the 600 and 800 Series. Andy chose to design a block-style inlay as a visual reference for the guitar’s big, bold and powerful voice, but upon closer inspection, there is an additional level of subtle detailing in the inlay — the mother-of-pearl block in the center is actually surrounded by an outer ring of laser-cut ivoroid that offers a subtle element of gradation. (For more on the technical execution of that inlay design, see our sidebar.)

“It feels appropriate for a Grand Orchestra guitar,” Andy says. “It embodies how I’d describe the sound of a Grand Orchestra. It’s powerful, bold, domineering, but also with this level of complexity and refinement that belies its sheer size. You can use a piece of inlay — a position marker, a mere decoration — as a design opportunity for the guitar to affirm itself because all the elements tell a similar story. When you look at the completed instrument as a player, you intuitively understand that the parts blend harmoniously. To me, that’s a successful inlay. I’d like to think that a hundred years from now, a player could look at that guitar and somehow intuitively know it all works.”

It probably would sound pretty amazing, too.

In a future edition of Wood&Steel, Taylor’s Director of Natural Resource Sustainability, Scott Paul, will offer a closer look at our sourcing efforts relating to natural materials like mother-of-pearl and abalone.