Bob Taylor has a saying that’s become something of a mantra around the Taylor campus. It comes up in discussions about long-term strategic decisions, often about embarking on ambitious projects with many initial challenges that may not pay immediate dividends but show great promise down the road. “In 10 years, we’ll be glad we did it,” Bob will sometimes remind everyone in an effort to consider the long view, not just the immediate impact. It’s a phrase that comes to mind in reflecting on what has grown into The Ebony Project in Cameroon.

As readers of Wood&Steel may recall, a decade ago, in 2011, Taylor Guitars and our Spanish tonewood supply partner, Madinter, purchased the Crelicam ebony mill in Yaoundé, Cameroon, with the goal of creating a socially responsible value chain for ebony musical instrument components. After spending the first several years adapting to the realities of operating in Cameroon, rebuilding the mill, training employees to use new machines and tools, and changing our sourcing specifications to reduce waste and increase yield (e.g. using ebony with variegation and not just the pure black wood), we turned our attention to another facet of responsible supply management: developing a scalable ebony planting initiative.

In 2016, the initiative was officially launched as The Ebony Project. We partnered with the Congo Basin Institute (CBI) in Yaoundé with the initial goals of conducting basic ecological research on ebony propagation (surprisingly little research on ebony was available) and leveraging what we were learning to develop nurseries and a community-based planting program that eventually could be scaled up. The first milestone target was to plant 15,000 ebony trees along with an undefined number of fruit trees as a food and income source for villages that participated in the program.

Over the past five years, The Ebony Project has made slow but steady progress, and we’ve been learning a lot. In 2020, we surpassed our goal of planting 15,000 ebony trees, and the project’s lead researcher, Dr. Vincent Deblauwe, has published scientific papers that are quickly becoming the definitive syllabus for the species.

Each year, the project team produces a progress report to document the successes and challenges of the previous year and articulate goals and opportunities moving forward. The reports are intended to be an honest assessment of the state of the project at each given moment in time and are publicly available, so if you’d like to read more, you’ll find the latest report at crelicam.com/resources.

As the project has evolved in recent years, we signed a public-private partnership with the government of Cameroon, and both the Franklinia Foundation and University of California have provided some funding. But by and large, thus far the entire endeavor has been personally funded by Bob Taylor.

Expanding with Outside Funding

After slowly establishing proof of concept with our community-planting paradigm, the work of The Ebony Project has attracted greater attention — and now additional funding. The Ebony Project will be included within a broader $9.6 million forest conservation initiative in Cameroon funded by the Global Environment Facility. (The GEF is a multilateral trust fund whose financial resources enable developing countries to invest in nature and support the implementation of major international environmental conventions on issues such as biodiversity, land degradation and climate change. The Government of Cameroon and the World Wildlife Fund will manage GEF funds in Cameroon).

The Congo Basin Institute will receive funds from the GEF grant that will allow us to build on our experience of the previous five years and expand from planting in six villages to planting in 12. The investment will also bolster the project’s already groundbreaking scientific research into the ecology of West African ebony and the Congo Basin rainforest. It’s an exciting moment for the project… but wait, there’s more.

Increasing Fruit Tree Production

The U.K. government-funded Partnerships For Forests (P4F) program has partnered with CBI to better understand the possibilities of expanding The Ebony Project’s fruit tree production and explore ways to access local and regional markets as an economic incentive to keep biodiversity intact, while further addressing food insecurity issues. Though we call the initiative “The Ebony Project,” planting locally desirable fruit trees was always part of the equation, although, truthfully, the fruit tree aspect of the project has lagged behind the ebony planting and scientific research. But it’s been getting better each year, and perhaps with P4F we can improve it further. Depending on the results of the analysis, P4F is poised to invest further to help enhance fruit tree nursery production and stimulate trade.

Meanwhile, Dr. Deblauwe and his team continue to make crucially important scientific discoveries that expand our understanding of the Congo Basin’s rainforest ecology. In fact, that project-based independent research was instrumental in the 2017 IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List re-evaluation of West African ebony, originally classified as “Endangered” 20 years earlier but subsequently moved to the more optimistic status of “Vulnerable.” (To learn more about that re-evaluation, please see my Sustainability column in W&S Vol. 94, Summer 2019). The project has improved our understanding of the multi-year fruiting cycle of ebony, and innovative night-vision trap cameras have identified, for the first time, the insects that pollinate the ebony flower and the mammals that eat the fruit, carry the seeds in their digestive tract, and disperse them through defecation, thus helping the tree reproduce.

Developing a Powerful Data Dashboard Tool

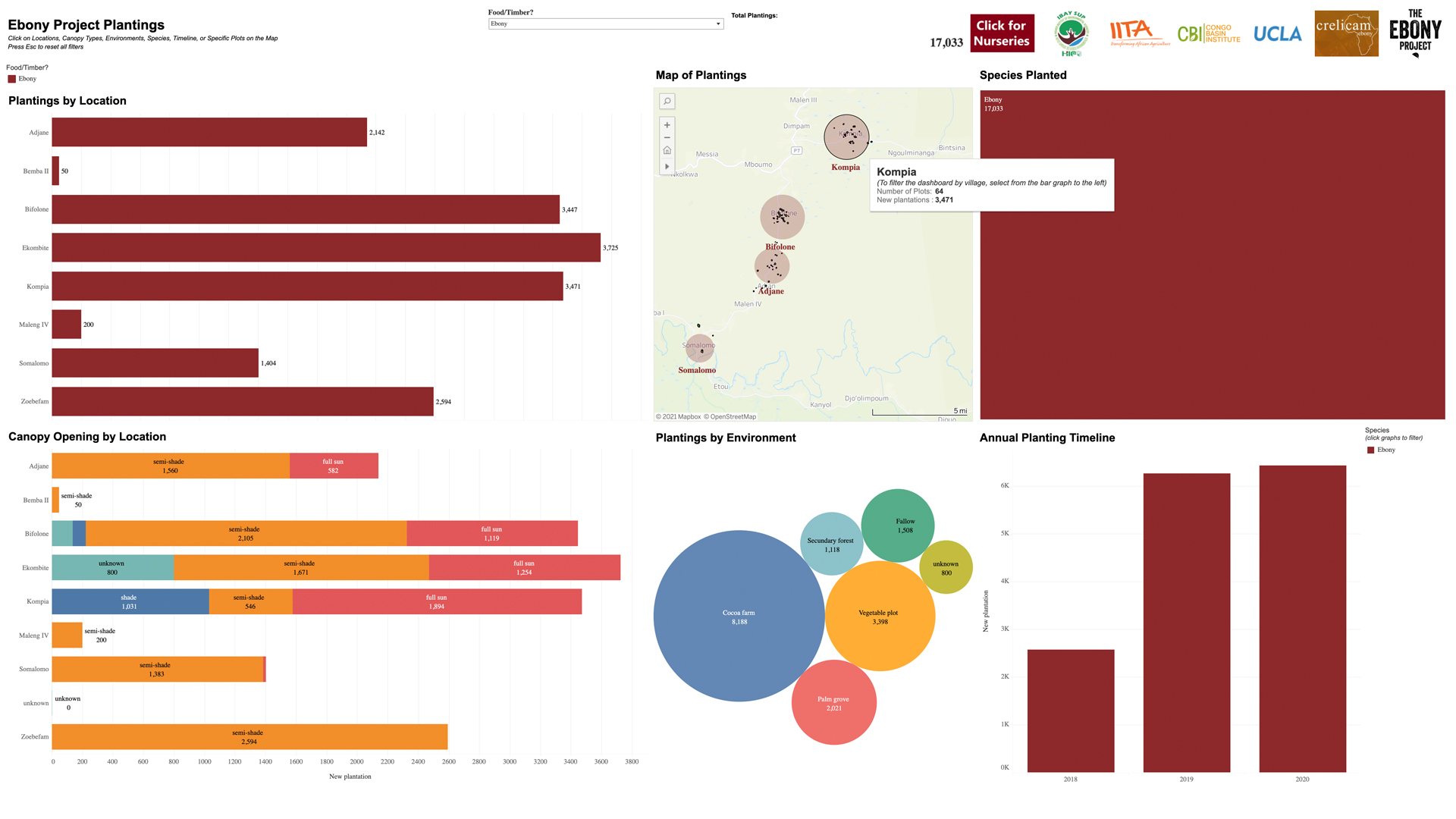

Meanwhile, Steve Theriault, our Business Intelligence Manager at Taylor, has been working with Dr. Deblauwe to convert project data that has been collected by hand or on laptop into Tableau, an interactive data visualization software platform. Tableau was originally created to help companies better understand operations through data analysis, providing historical, current and predictive views, including graph-type data visualizations. It’s cool. And Steve is the equivalent of a triple black belt in Tableau. What he and Vincent have created is incredible. With a few clicks, a highly intuitive dashboard allows us to share information in an easily understandable way. At any given moment, we know, for example, how many ebony and fruit trees are in any given nursery and what year we expect they will be ready for transplant. We can track annual seed collection, and we know who planted what and where. We run macro queries across the entire project or zoom in and analyze village-level data. It’s really going to be helpful and I think somewhat unique within the global restoration movement.

Entering Phase 2

I’ve taken to calling the first five years of The Ebony Project “Phase One: The Start-up Years,” which were largely paid for by Bob Taylor. We had our successes and failures, we grew our community planting partnerships to six villages, and we hit our goal of planting 15,000 trees. We learned a lot about the basic ecology of the species and about the communities of people that live in the extended buffer zone of the Dja Forest Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, where we work. Bob and CBI founder, Professor Tom Smith of UCLA, set up an endowment to ensure the project’s survival into the future, regardless of outside funding.

By 2025, we aim to plant an additional 30,000 ebony trees and 25,000 fruit trees.

Now, with funding from GEF and P4F, along with Franklinia and the University of California, we have entered Phase 2 and will double the number of villages that would have otherwise been supported. And we have a new five-year goal. By 2025, we aim to plant an additional 30,000 ebony trees. For the first time, we also have a fruit tree planting goal: 25,000 trees in the next five years. If successful, we will have enhanced the biological integrity of the area adjacent to the Dja Reserve, helped local communities overcome food insecurity issues, and maybe, just maybe, someday long after we’re all dead, someone can buy one of the ebony trees we’ve planted to make a guitar.

Phase 3?

Finally, allow us to dream. We can’t help but look beyond the current project area, the Dja UNESCO World Heritage Site, and across all of Southern Cameroon, and further still into an area referred to as the Tridom, a vast area that includes portions of Southern Cameroon, Gabon and a bit of the Central African Republic. It’s said to be the most intact forest block left in the Congo Basin. The so-called Tridom region is home to a dozen or so large protected areas. Of course, people live here — traditional peoples since long before recorded history, and more recent settlers, too. There are roads and towns, logging and agriculture. But it makes us think. If over the next five years, The Ebony Project is successful in the Dja region of Cameroon, it would be interesting to replicate the model around similar protected areas within the Tridom. That, I hope, is a subject to explore in a future edition of Wood&Steel.

Hawaii Reforestation Update: Planting Koa

We wanted to share an update on our latest forest stewardship work in Hawaii. As a recap, back in 2015, tonewood sawmill/supplier Pacific Rim Tonewoods and Taylor Guitars formed a company called Paniolo Tonewoods. Our joint mission was to work toward preserving a healthy future supply of koa for musical instruments by regenerating native forests that include koa trees.

Paniolo’s initial projects in Hawaii borrowed from an arrangement first implemented by the U.S. Forest Service, exchanging value of wood for services provided. Instead of paying the landowner directly for koa logs or harvesting rights, Paniolo was allowed to cut a select number of designated koa trees, and in exchange, agreed to pay for a host of forest improvement projects on the land. These improvements, whose value equaled that of the wood harvested, included installing new fencing to keep feral sheep and cattle out, removing invasive plants, improving fire breaks, and planting and maintaining koa seedlings grown in nurseries.

As we previously reported, another initiative was set in motion in 2018, when Paniolo acquired 564 acres of rolling pastureland on the north end of Hawaii Island. This land will continue to be managed by Paniolo, which was tasked with returning much of the land to a native Hawaiian forest after having been cleared for pasture about 150 years ago. The plan was for Paniolo to plant a mixed-species native koa forest for future timber production when the forest is mature beginning roughly 30 years after planting and continuing in perpetuity. The planting is projected to yield more than twice the volume of koa wood that Taylor Guitars uses today via selective cutting and replanting of trees.

This past June, Paniolo Tonewoods began to turn back time by planting over 3,000 koa and a little over 800 mixed native tree and shrub species on 10 acres of the property. Afterward, Paniolo project manager Nick Koch shared more details about the land, the planting and the plans ahead.

“The picturesque land of Kapoaula sits between the two historic ranching communities of Waimea and Honoka’a, with a rich history of Paniolo culture. Cattle grazing has been a way of life here since the 1850s, a tradition that continues to this day but has also resulted in the demise of native forests. Not only here but throughout Hawai’i.

“The views from the property to the surrounding valleys and mountains are spectacular. On a good day you can even see the distant island of Maui in the haze. These views will be lost to the growing trees in the next 10 to 15 years, but we believe it is a price well worth paying for a property that will ensure the future availability of koa for Taylor guitar making. Sweeping views will be replaced by lush native forest with an abundance of healthy, maintained koa trees and plentiful habitat for native birds. Wood is, after all, the ultimate renewable resource, and through projects like this, we are indeed doing our part to renew the forests and ensure their future health.

“In the next decade, our plan is to plant 150,000 trees on this property. In the last year, Paniolo has planted 3000 trees. We’re starting small to minimize our mistakes as we continue to learn how to cultivate healthy trees.”

Please Use Fewer Plastics. We’re Trying, Too.

Last issue, Jim Kirlin wrote about our recent efforts to better understand the use of plastics in our manufacturing process. The article (“Bad Wrap: Inside a Growing Plastic Problem”) discussed issues related to our use of plastic stretch wrap to secure pallets stored or moved from one place to another.

As we began to better understand the issue, we learned that we no longer had what we once thought was a responsible way to dispose of our used shrink wrap. So, Bob Taylor and I decided to stack it up in the center of the main parking lot where employees could see it. Bob told me, “Until we figure something out, we’ll just keep it there, and we’ll all watch it grow.” So we did. And the pile grew. Meanwhile, a group of us has been working on the issue. We did more research. We talked about it in our employee newsletter, and soon stories of small innovations and reductions started coming in from across the campus. We posted the story on social media and received (mostly) encouragement and a few helpful suggestions, too. Thanks for that!

Soon, we hope to tell you about what we believe will be a major step forward in reducing our plastic footprint. We’ve connected with a company that may offer a viable solution, and right now we’re cautiously optimistic. It will only be a first step, but the first step is always the most important. Plastics are a huge problem across the planet. The statistics are sobering. It’s going to be a long and difficult road, but we all need to get on it. Stay tuned for an update in our next edition.