It had been four years since I last visited Cameroon. As part of my responsibilities under the Taylor Guitars Ebony Project, I used to go regularly to meet with team members at The Congo Basin Institute and to visit project sites where participating villages plant ebony and fruit trees. It was also a chance to get caught up on the latest scientific research being conducted by Dr. Vincent Deblauwe and his team. As readers of Wood&Steel may recall, the Ebony Project was launched in 2016 with the objective of conducting basic ecological research and planting ebony and fruit trees. If you’re interested in the details, annual progress reports can be found at crelicam.com/resources.

After achieving our original goal of planting 15,000 ebony trees in 2021, the project established new goals of planting an additional 30,000 ebony and 25,000 fruit trees by the end of 2026. To date, Bob Taylor has personally paid for almost all of it. Others have contributed, and Taylor Guitars provides a lot of in-kind support.

On March 19, 2020, just as Bob and I were preparing for a spring trip to Cameroon, everyone at the factory here in El Cajon was unexpectedly told to go home. COVID-19 had come to San Diego, and trips to Cameroon — trips anywhere — were off the table. Three years later, this past February, Bob and I finally made the trip back. In the lead-up to going, however, I found it hard to wrap my head around the fact that I hadn’t visited since April 2019. The pandemic really did play with my perception of time. But now that I’m home, having visited and returned, it all makes sense. The project has grown, and seeing the change seemed to put time in context. So, I thought it was a good opportunity to provide a project update.

Joining us on the trip was Cameroonian-American singer-songwriter, guitarist and actress, Andy Allo. Andy, the daughter of a well-respected ecologist, was born and raised in Cameroon but left when she was thirteen years old. She had not returned since. As fate (and talent and hard work) would have it, Andy grew up to play guitar in Prince’s band the New Power Generation. She’s put out several solo records and is currently an actor on the T.V. show Chicago Fire, the Amazon series Upload and Star Wars: The Bad Batch on Disney+. Andy plays a Taylor, and when she wanted to learn more about what we’re doing in Cameroon, our Director of Artist Relations, Tim Godwin, and I drove up to L.A. to have lunch with her. By the time the check arrived, she was fully committed to joining us on our next trip. Yes, she’s awesome.

Fast Forward

I met Andy at the airport in Paris, where we both connected for a flight to Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital, that would arrive that evening. Bob had traveled a few days earlier to spend some time at the Crelicam mill. He and the mill’s director, Matthew LeBreton, met us coming out of baggage claim. It was midnight by the time Andy and I stepped into the humid tropical air. Andy, having grown up in Cameroon, acclimated with ease, but I was born and raised in Massachusetts, and my body will never get used to it. I began to sweat. I was back in Cameroon.

In 2022 alone, 6,372 ebony trees were planted across all project sites, bringing our total to 27,810.

A few days later Bob, Andy and I joined Dr. Vincent Deblauwe and his team for the long drive to Somalomo, where the Congo Basin Institute has a research station just steps from the Dja River, the other side of which was the Dja Forest Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site established in 1987. There are now six villages along the road that leads to Somalomo that participate in the Ebony Project. There were only three the last time I visited. Additionally, there are now also another two on the far side of the Dja Reserve, bringing our total to nine (including Ekombite, a village closer to Yaoundé). I would visit these two new villages on a separate trip a week later, but for now, I was focused on where I was, a place I had been several times before. Quite frankly, I was shocked by how much the project had grown.

In 2022 alone, 6,372 ebony trees were planted across all project sites, bringing our total to 27,810. The project also planted 5,402 fruit trees last year. On this day, village nurseries were flush with young ebony and fruit trees ready to be planted in a few months when the rains came. Villagers expertly demonstrated their fruit tree grafting skills, a horticultural technique practiced for centuries to propagate plants but introduced to the project villages only a few years ago. Several of the fruit trees planted at the beginning of the project were now bearing fruit and feeding people. The promise of hundreds more was on the horizon, perhaps only a few years away. Several of the ebony trees that I saw planted years ago were now as tall as I was, some taller. We hear repeatedly from every project participant that the planting of ebony helps clarify local land tenure.

While land ownership in Cameroon is complex, there may be grounds for program participants to have their individual ownership of the trees they plant recognized by the national government. This year, the Ebony Project fully implemented sylvicultural booklets across all of the project sites to help document who planted what, where and when. While these booklets themselves do not provide land tenure, they do contribute evidence for both local/customary ownership and formal recognition.

A Moment of Reflection

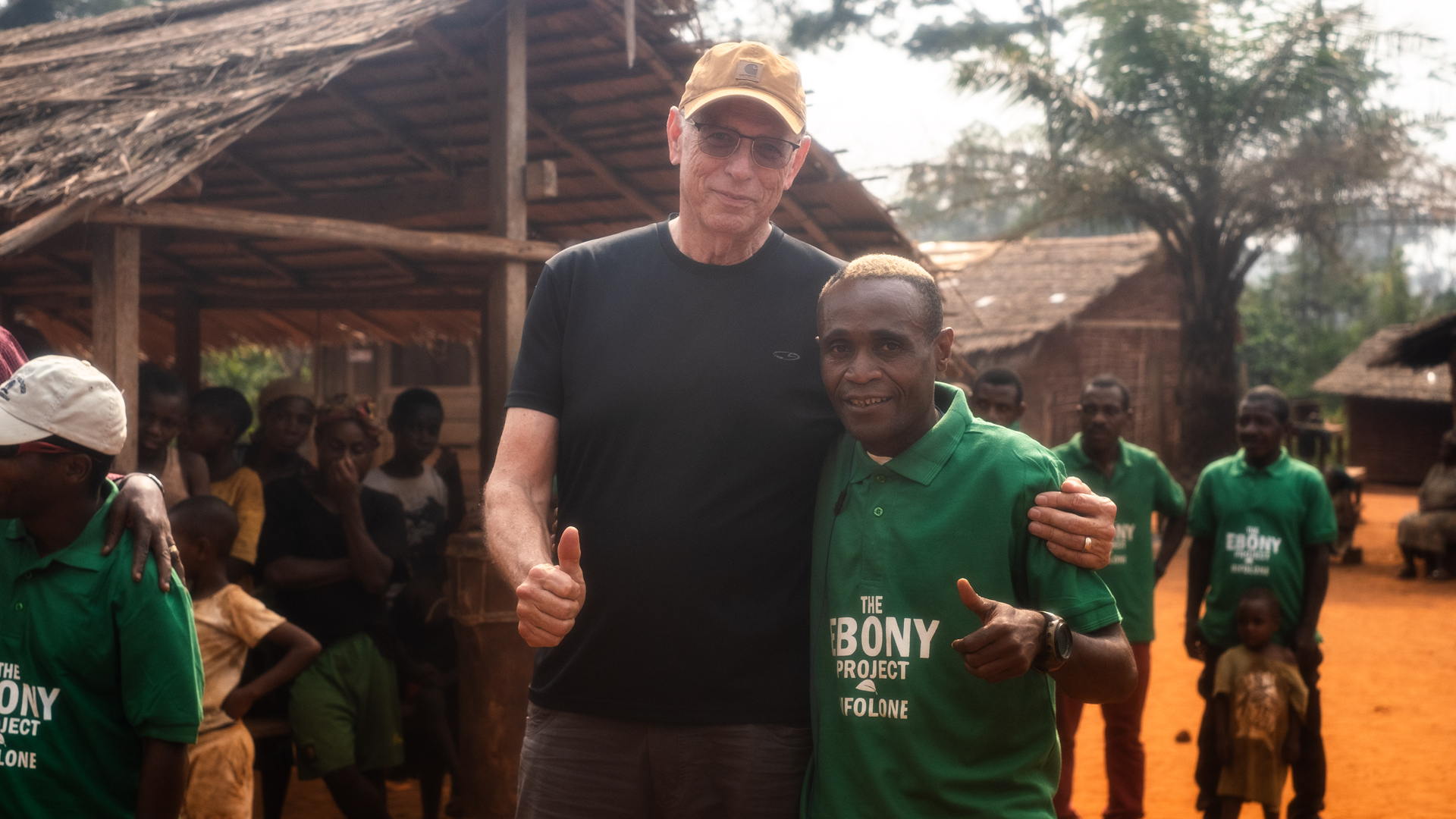

Taken in its entirety, our visit to these six villages was extremely rewarding. Four years had indeed passed. It was clear to me. But for me personally, it was most rewarding to see Bob’s reaction. Bob has been to Cameroon countless times over the past 11 years and spent hundreds of hours at the Crelicam mill in Yaoundé. But this was his first opportunity to visit the Ebony Project field sites, and what was once theoretical was now unfolding right in front of us. He had paid the lion’s share to make it happen, and you would have to be made of stone to not be moved by what we were seeing.

Wash, Rinse, Repeat

A few days later, we were all back in Yaoundé. Time for showers and laundry. Bob prepared to return to San Diego. Andy had a few more days that she would spend visiting childhood places and friends, and connecting with the local music and arts scene. Meanwhile, I prepared for a trip to the new project area in and around Zoebefam, southeast of the Dja Reserve. The project wasn’t active in this area the last time I was here, but one village was already in its third year of planting; another was on its second.

Several of the ebony trees that I saw planted years ago were now as tall as I was, some taller.

On this trip, I was joined by Virginia Zaunbrecher from UCLA. Since the Ebony Project’s inception, Virginia and I speak regularly. She and I are the major points of communication between Taylor Guitars and UCLA, who oversees the Congo Basin Institute. Vincent, of course, came along. And so did his three project managers: Jean Michel Takuo, Zach Emanda and Josiane Kwimi, three Cameroonians who each have a degree in agroforestry. They, too, were new to the project since my last visit, but they each now seemed like old hands, and I was looking forward to spending time with them in what promised to be a quieter, more intimate setting than the trip a few days earlier.

Upon arrival to the new project area, I was struck by how different it was. And how much it was the same. It’s hard to explain. The region felt more forested. Fewer people from the outside visit here. Fewer international projects have worked here. But in many ways, it reminded me of being in the Somalomo region five years earlier when the project was first being introduced. It was inspiring, yet felt tenuous. I could only hope that in five years, the project would take root and grow in a similar fashion to the villages around Somalomo. But I knew that each region, each village, presents unique challenges. Some villages are Bantu, and some are Baka. This brings politics that I myself am just beginning to understand but that, thankfully, are understood by the project team. Some villages have active participation from multiple members of the community; others have a small handful of champions doing the work. Each village has varying degrees of challenges with food insecurity, access to fresh water, healthcare and education.

We slept in tents and cooked over the fire. At night and in the car rides to and from the villages, the team and I talked about the Ebony Project — what was working, what was needed, and the pending challenges of expanding to new villages. After several years of negotiations and waiting (and more negotiations and waiting), the first allotment of a $1 million, 5-year project grant from the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) would soon be released, and with it the Ebony Project will expand to three more villages. But which villages? And where? Should we expand along the road near Somalomo on the northwest side of the Dja Reserve, or were there opportunities to consolidate our foothold and grow on the southeast side near Zoebefam? Should we attempt to open a new project cluster on the eastern edge of the Dja Reserve near Lomié? There were pros and cons for each option with financial, logistical and staff capacity considerations. There was a lot to learn. A lot to think about. I was grateful to have such a talented team at the Congo Basin Institute to work with.

When I returned to Yaoundé a few days later, Bob and Andy had left. The house was empty. Vincent, Matthew, Virginia, Jean Michel and I met with representatives of the Cameroonian Government, the GEF and the World Wildlife Fund about the soon-to-be-released funds and our plans to expand the project. Over the next few months, the team will have to figure it out. But I am confident.

The project’s slow, methodical growth has been our secret sauce, a reflection of the flexible and adaptive philosophy of Bob Taylor.

The project’s slow, methodical growth has been our secret sauce, a reflection of the flexible and adaptive philosophy of our primary funder, Bob Taylor, who brought a business-centric start-up mentality that has been critical to our success. It was the same approach he and Kurt Listug used to build Taylor Guitars. Simply put, when something was not working, it was discussed and revised. When something was overly complicated, it was simplified. Despite the considerable strings attached to receiving funds from a large multilateral institution like the GEF, I am confident. Learning this new bureaucratic dance will make us stronger and hopefully prepare us to expand again more dramatically years from now. But for now, our goal is to plant an additional 30,000 ebony and 25,000 fruit trees by the end of 2026, and to expand to three more villages. Vincent will soon release a new peer-reviewed original scientific research paper that I hope to talk about in the months to come. And I have a feeling that we have not seen the last of Andy Allo in connection with the Ebony Project.

In 2021, I wrote an article in Wood&Steel titled “The Ebony Project: Growing Into Phase 2.” In it, I dreamed of a day when the Ebony Project would expand beyond the Dja Reserve, across all of southern Cameroon, and one day, further still into a region referred to as the Tridom, a vast area that includes portions of southern Cameroon, Gabon and a bit of the Central African Republic. I still have this dream, albeit with a slightly more realistic understanding of what it would take. But it can be done. The plan is working. The team is small but excellent. And that, I still hope, will be the subject of a future edition of Wood&Steel.