Taylor’s 50-year milestone certainly is an occasion that warrants retrospection and invites questions from players and admirers of our company. One common question for Bob and Kurt has been whether, back when they began, they ever imagined what 50 years of business would be like. Bob and Kurt certainly have their own perspectives. (See each of their columns this issue.) Since I wasn’t there at the time, I can only speak from my own experience. Truthfully, when I started working with other players and their instruments on my own more than 30 years ago, I was way too young to think that far into the future.

Maybe some youngsters have the capacity to think 20, 30, 50 or more years into an unwritten future, but I certainly didn’t. I wasn’t even thinking that working with instruments was something that fell under the classification of work. Guitars and music were fun and games. Really exciting fun and games. When I had a player’s instrument to work with, my thoughts were confined to considering what I could do to make the instrument good for that person and little about the future. I confess that this pattern of thinking tends to stick with me even now. It’s hard to think about anything else when I have a guitar in front of me. As a result, milestones tend to catch me by surprise.

Within the focused daily rhythm of working with the instrument in front of me, there is an element of direction that indeed guides the shape of a future. While I have rarely given much thought to what a 50-year-old company might be like, nearly every day I’ve thought to myself, “If you’re going to make a guitar, try to make it good guitar.” That guiding thought accompanies me to individual tasks — work hard to make that fret job a good one, or set up that guitar with the string height that works the very best, or a thousand other things that go into making a guitar good for a player. Over a long enough span of time, little daily decisions like that ultimately shape the scope of the work. In other words, simply trying to make better guitars each day helps to steer the kind of company we are.

I’m not saying great things happen by accident — a company with longevity isn’t formed by chance. It is established with will, effort and persistence. But it is achieved with daily, even hourly tasks guided by the intention to do a good job.

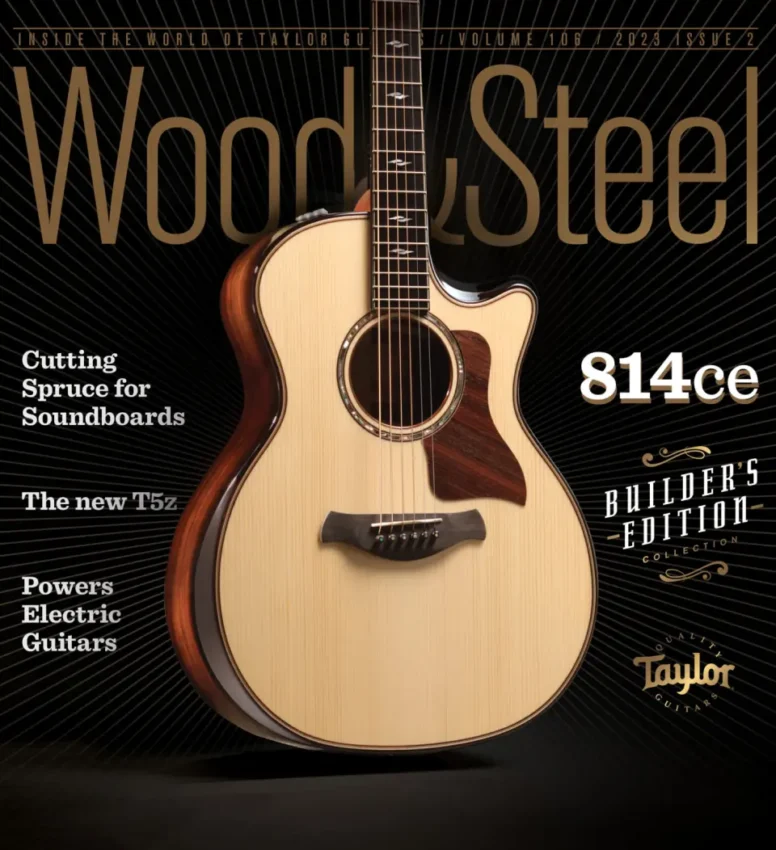

Our desire is to build the best guitars. I hope that intention is felt in the instruments we create.

If you’ve been reading Wood&Steel for a while, you’ll know that Bob really likes camping. Some years ago, Bob decided to buy a little camping trailer he could tow out into some remote place and still have some comforts of home. When the trailer arrived, we spent some time looking at it and felt a quiet sense of disappointment. Bob was first to speak up and commented that it looked like it had been built by a person who hated their job. Or was at least indifferent. He was right. The thing was there, and it was the camping trailer it claimed to be, but something was off. He immediately started plans to rebuild it and turn it into what he wanted it to be.

That poorly built camping trailer was a good example for me when thinking about guitars, and why it is that as guitar players, we know when something seems off, even when we can’t clearly point to a specific detail. It’s as if in playing music, we can sense both the skill and, importantly, the intention of the maker that went into an instrument. When we build a Taylor guitar, our intention is to build a good one. I’m not saying we always get it perfect. There are plenty of occasions when a detail is accidentally overlooked, or a mistake is made. Those errors bug me, and they compel us to do better each day. Occasional error notwithstanding, our desire is to build the best guitars and work toward that each day. I hope that intention is felt in the instruments we create.

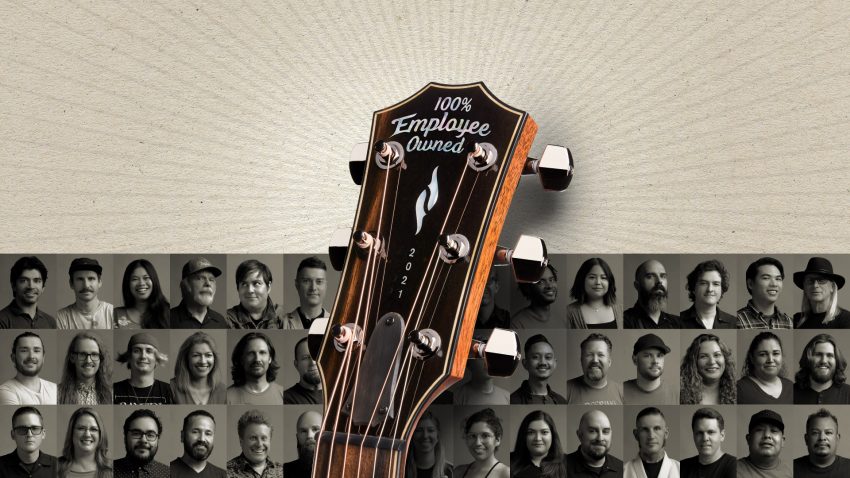

As we glance back at the time and body of work that has brought Taylor Guitars to its fiftieth year in business, it’s the perfect opportunity to ask ourselves what sort of company we want to be going forward. If you ask me, I’ll say I’d like to be the sort of company that seeks to do a great job in everything it does. To do a great job with the guitar in front of us and its player. To do a great job with the forest resources at hand. To do well with what is entrusted to us. To accomplish that will be lived out each day along the way to our next milestone.

I hope you’ll join me in congratulating Kurt and Bob on the company they’ve formed and fostered for five decades. I’m happy to be part of that legacy and offer my contribution to the instrument we love, and the community of players who enjoy these guitars we make. I’m eagerly awaiting the adventure into the next 50 years and working that out one day at a time.