Mahogany is often called the “King of Woods.” Used by native peoples across Central and South America for time immemorial, the tree was noticed by Europeans during the Spanish colonization of the Americas and introduced into international trade as early as the 17th century. Steady imports into Europe, North America and, eventually, the rest of the world continue to this day. Mahogany was introduced on steel-string guitar necks in the early 1900s when American luthiers noticed it being brought into New York to make wooden molds for iron foundry castings, and for furniture. Locally abundant, it made sense for companies like C.F. Martin to use it as a substitute for Spanish cedar, given its similar characteristics. A century later, mahogany remains the most utilized wood for guitar necks, and today it is common to see it also used for guitar backs, sides and soundboards too.

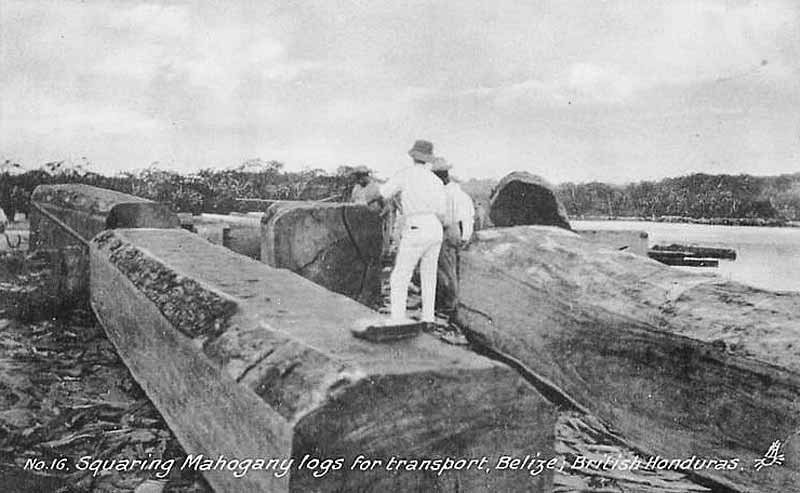

Squaring mahogany logs for export in British Honduras (later renamed Belize) in the 1930s. Source: Handbook of British Honduras by Monrad Metzgen and Henry Cain.

A Rose by Any Other Name

As many guitar enthusiasts might have noticed, the word “mahogany” is often preceded by a descriptor, such as Big-leaf, Honduran, tropical, neo-tropical, genuine, Fijian, Indian, African or Philippine. It can get confusing, especially considering that some of these examples are referring to species that are taxonomically unrelated, meaning they are not even from the same genus. In short, it’s not the same tree. Yet they are all called the same. Why? Simply because since it was first introduced into international markets, mahogany has remained so popular that almost any lumber that looked like it, and that had similar physical properties, was marketed as it.

I’ve bought bottles of sparkling wine marketed to me as “champagne” that were not technically champagne because the grapes were not produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the “rules of the appellation.” I was blissfully ignorant. But at the risk of insulting an entire nation, I was fine with it — I ushered in the new year; it did the job. And historically, that’s the way it’s been with wood. Remember, humanity didn’t really start examining broader ecosystems or conducting species-level analyses, especially in the tropics, until after World War II. So, until relatively recently, when it came to wood, especially from the tropics, almost everyone has been blissfully ignorant, and, until recently, few cared.

But this is all changing. It has to change because we can’t unknow what we now know. Science is naming, describing and classifying living organisms at an astounding rate, unlocking behavioral, genetic and biochemical variations explaining how life on Earth works. It’s important stuff, especially in a time when eight billion people are devouring the planet’s natural resources at an ever-increasing rate.

If you believe in concepts like “sustainable development,” then you would have to agree that it’s important to understand what species of tree we’re cutting, trading and, yes, building guitar parts out of. We need to develop a more sophisticated understanding than we needed to not that long ago, not only because it’s morally correct (and ultimately our survival may depend upon it), but because, increasingly, it’s also the law. For example, as readers of Wood&Steel might know, more and more commercially traded timber species are being listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). So, as a guitar builder, it’s important to document exactly what species, what genus, of wood we’re bringing into the country because, increasingly, different levels of compliance and documentation are required.

In the words of Bob Taylor: “The easiest day to buy wood to build guitars is today, because tomorrow is going to be harder.” Bob’s right, of course, but I would just add “…harder, but not unmanageable.” As a company, Taylor Guitars is now organizing, digitizing, tracking and monitoring our wood use like never before. And, as a result, we’ve decided moving forward to just say “mahogany” when describing our finished guitars, and to drop any additional descriptor.

I understand that this might seem counterintuitive. Don’t we need more specificity, not less? Let me explain our thinking.

How We Got Here

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the first species of mahogany noticed by Europeans (Swietenia mahagoni) is what we commonly call Cuban mahogany today. It was perhaps first observed in Cuba. As the tree is native to the broader Caribbean bioregion, it is also sometimes called West Indian mahogany, hence that name. In the years that followed, a second species, what we today call Big-leaf mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), was noticed by Europeans on the mainland in Honduras. So, that’s why people sometimes call it Honduran mahogany, despite the fact that the species is native north of Honduras into Mexico and south of Honduras all the way into the Amazon basin. Its native range is considerable. The point is that just because someone told you your guitar is made of Honduran mahogany doesn’t mean the wood is actually from Honduras.

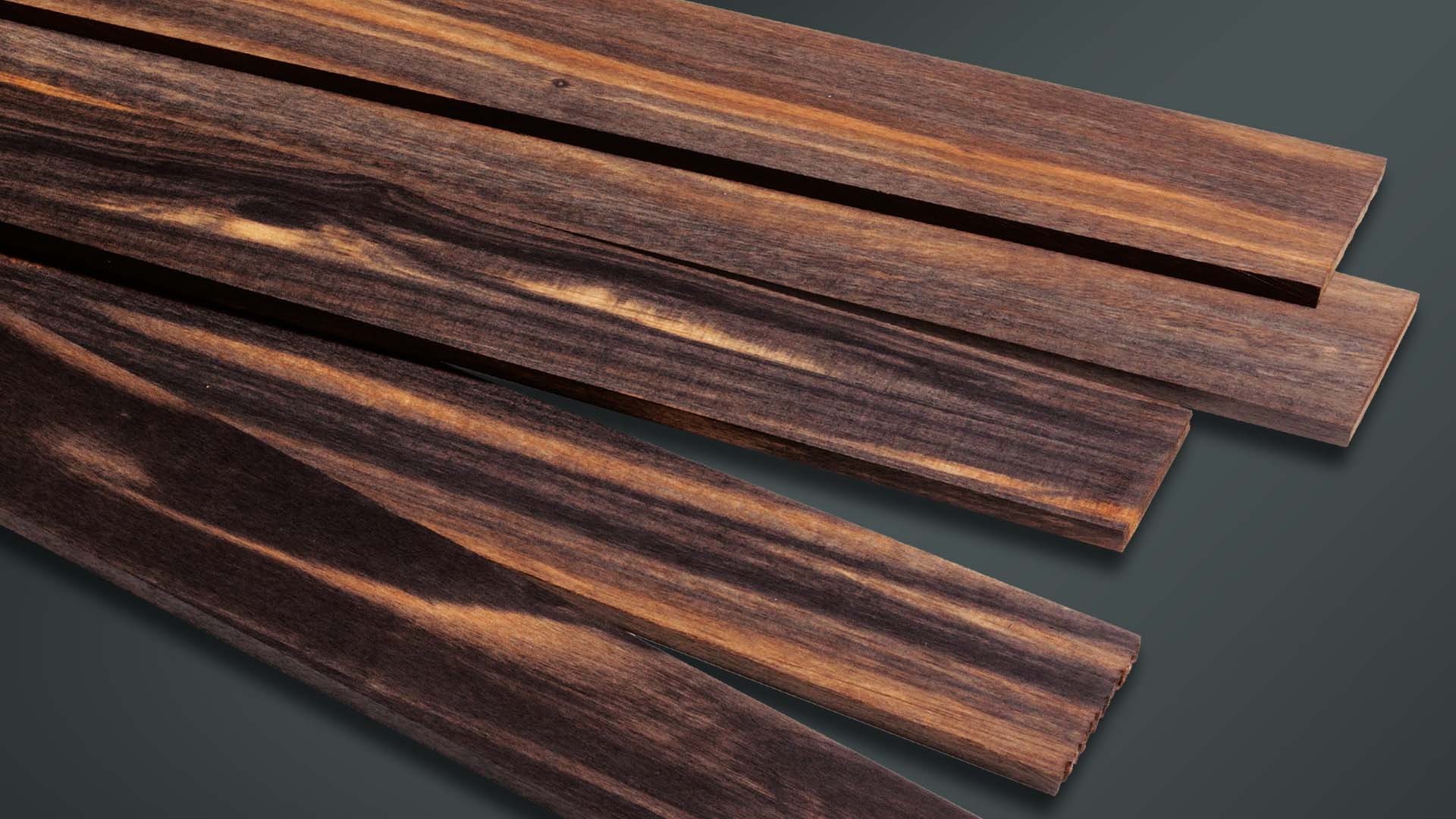

The historical range of Big-leaf mahogany

Incidentally, a third species of mahogany (Swietenia humilis) can be found on the Pacific Coast of Central America, but it’s a small tree and has limited commercial utility. Cuban and Big-leaf, however, do, and their eventual reputation as the King of Woods did not emerge from a marketing campaign. It was built over time based on their fantastic stability and woodworking characteristics. Characteristics deemed so valuable, in fact, that over decades and centuries, they were introduced as a plantation species across the world. Swietenia (Cuban, but mostly Big-leaf) can now be found in far-flung places such as Australia, Fiji, Guam, Hawaii, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, the Solomon Islands and Sri Lanka. Attempts to plant it in tropical Africa proved less successful, due in part to its inability to defend itself against certain insects that like to deposit their eggs on new leaves, ultimately resulting in mortality.

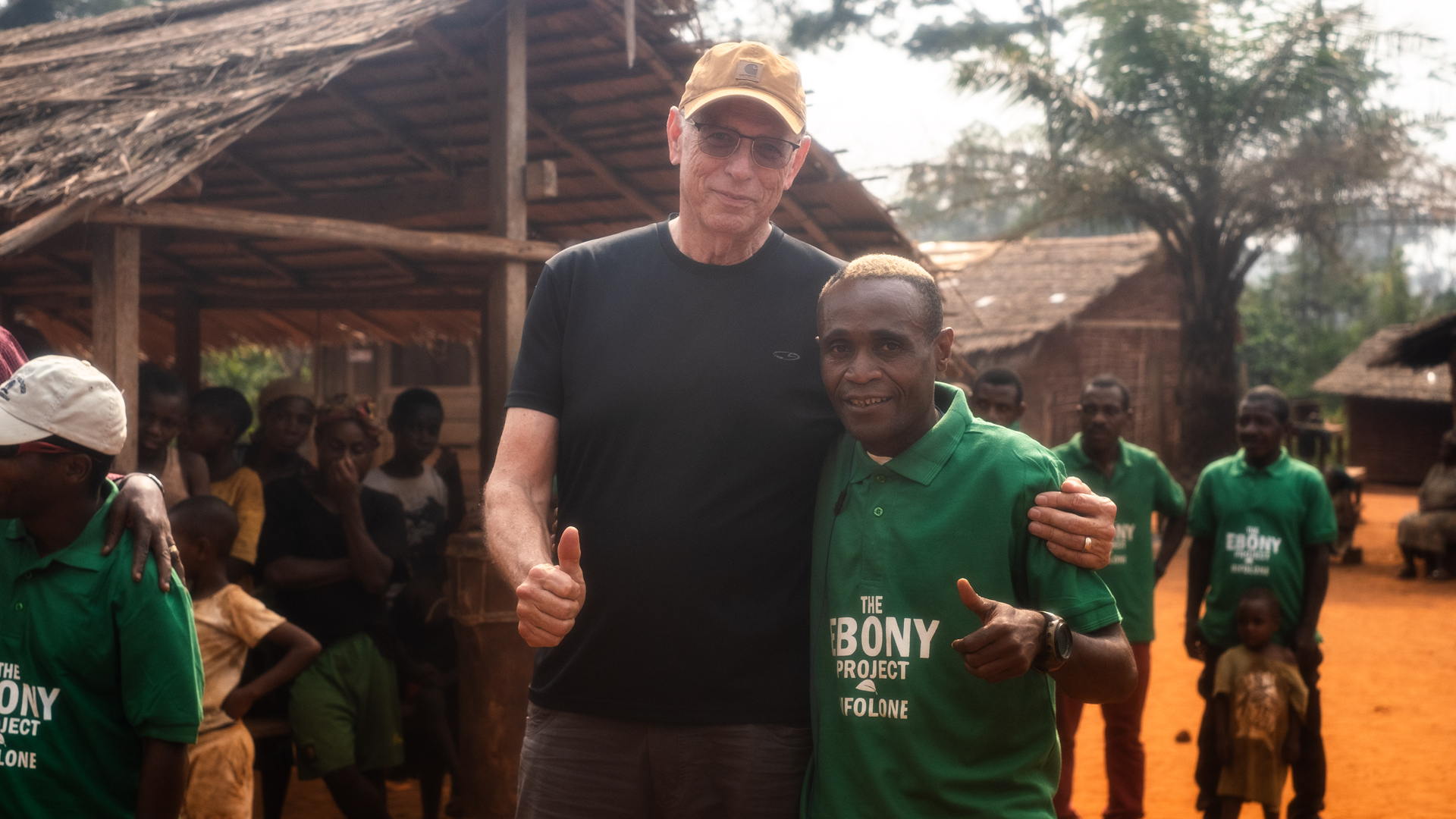

Bob Taylor in front of a mahogany tree that was planted by the British in Fiji.

But wait, if Swietenia didn’t fare well in West Africa, why do I see guitars made with African mahogany? The short answer is that several different West African tree species, genetically unrelated, each a different species and a different genus, were similar enough that they were simply called mahogany. Khaya (Khaya ivorensis), sapele (Entandrophragma cylindricum) and sipo (Entandrophragma utile) are examples of tonewoods commonly marketed as “African mahogany” although none are of the Swietenia genus. This, in and of itself, doesn’t mean that the wood makes a better or worse guitar part. And no, nobody tricked you, because for a long time, everyone just called these trees African mahogany. In many ways they are very similar, though accomplished luthiers have their own particular preferences for any given guitar part.

A Quick Recap to this Point

So far, we’ve established that “genuine mahogany,” meaning trees of the Swietenia genus, are native to the Americas and that Cuban and Big-leaf were so popular that their seeds were planted in many countries across the Tropics outside their natural range. Today, Taylor guitar necks are often made with genuine mahogany planted in Fiji, and for our back and sides, we typically use genuine mahogany from India planted long ago as boulevard trees. Such trees typically grow to large size and are thus big enough for a traditional two-piece guitar back. So, when you think about it, Taylor has been using urban wood far longer than our 2020 introduction of Shamel Ash or our 2022 introduction of Red Ironbark eucalyptus. We just never thought to mention it before.

A mahogany guitar body.

We’ve also established that several other tonewoods called mahogany are not “genuine mahogany” because they are of a different genus. Khaya, sapele and sipo are examples. Now, finally, to make matters more complicated, I’ll point out that in the late 1980s and early 1990s, genuine mahogany (a.k.a. Swietenia) was planted in the Philippines, but there have long been other species coming from southeast Asia, mostly of the Dipterocarp genus, that are marketed as “Philippine mahogany.”

Why does any of this matter? For a guitar player, maybe it doesn’t. The only thing that should matter is whether or not you like the guitar regardless of what collection of woods came together to build it. Pick it up and play it. Do you like it or don’t you? Don’t get hung up on what’s been marketed to you. However, for a guitar manufacturer, or for anyone who imports wood, it does matter because ethics and legality increasingly demand it.

Increased Regulation

By the late 20th century, with mahogany’s natural range across the Central and South America increasingly cleared or degraded, the aforementioned multilateral treaty to protect plants and animals from unsustainable levels of international trade, known as CITES, began to take notice. Initially, the concept of listing such a heavily traded commercially timber species was controversial. After several failed attempts, Costa Rica, then Bolivia, Brazil and Mexico unilaterally choose to list their populations of Big-leaf mahogany under the less burdensome Appendix III. To be honest, for such a listing, few, if anyone in the private sector needed to pay that much attention. But this all changed in 2002, when, after a high-profile campaign waged by Greenpeace, CITES voted to move “neotropical populations of Swietenia macrophylla” to Appendix II, requiring higher levels of transparency and documentation for governments and the private sector alike.

The story of mahogany and CITES is helpful for two reasons: It signals an early milestone for increased levels of protection for commercially traded high-value timber species; it also explains how the term “neo-tropical” entered into the lexicon of guitar makers. Neo-tropical denotes a zoogeographical region of North, Central and South America, south of the Tropic of Cancer. The neo-tropical distinction is important, as CITES intentionally decided to exclude Swietenia plantations, even if naturalized, introduced to places like Fiji, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and the Philippines, who by this time were major exporters of plantation-grown timber. Equally important, species that went by the common name “mahogany” but were not of the Swietenia genus, such as khaya and sapele, were all exempt.

The New Normal

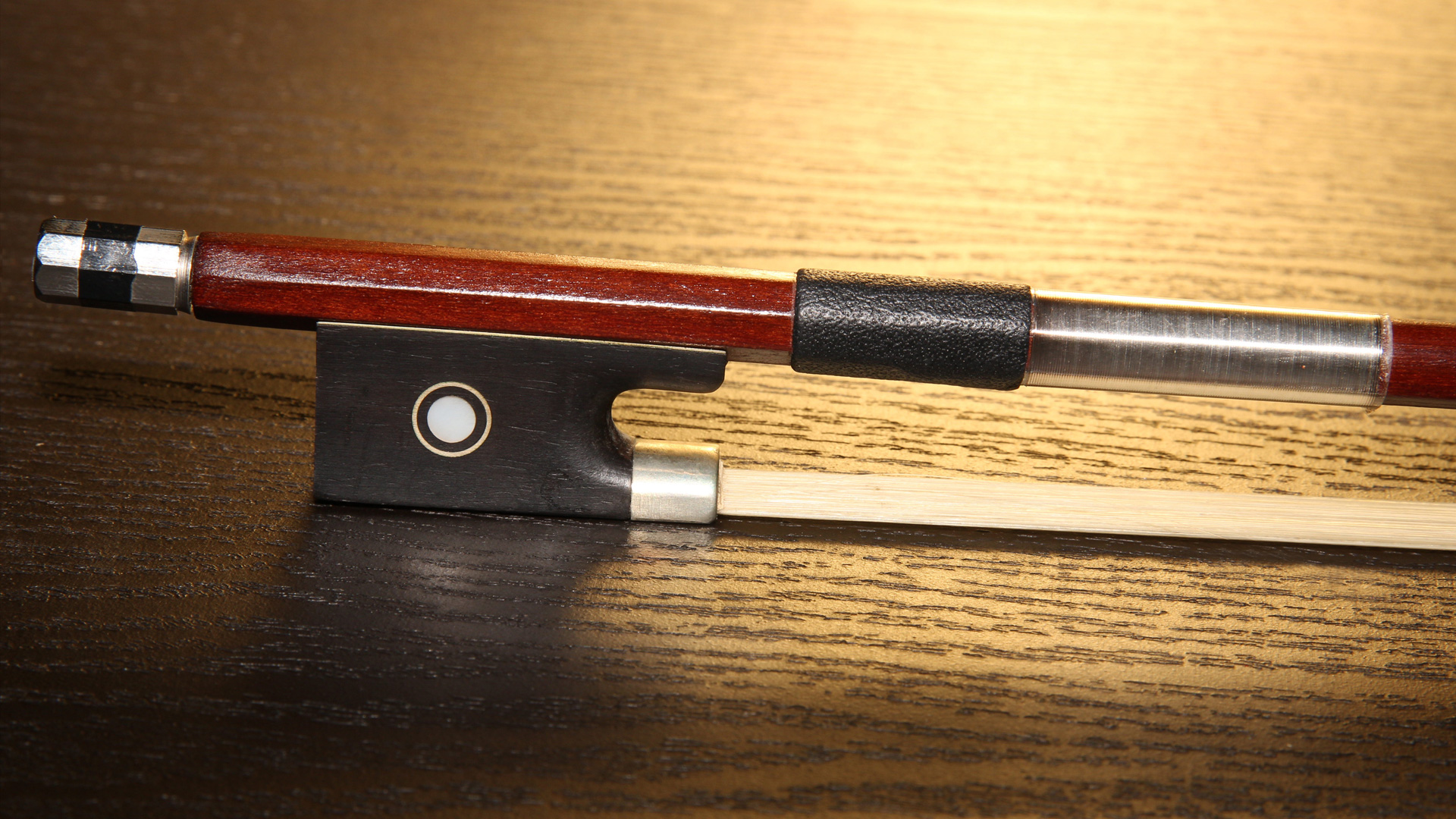

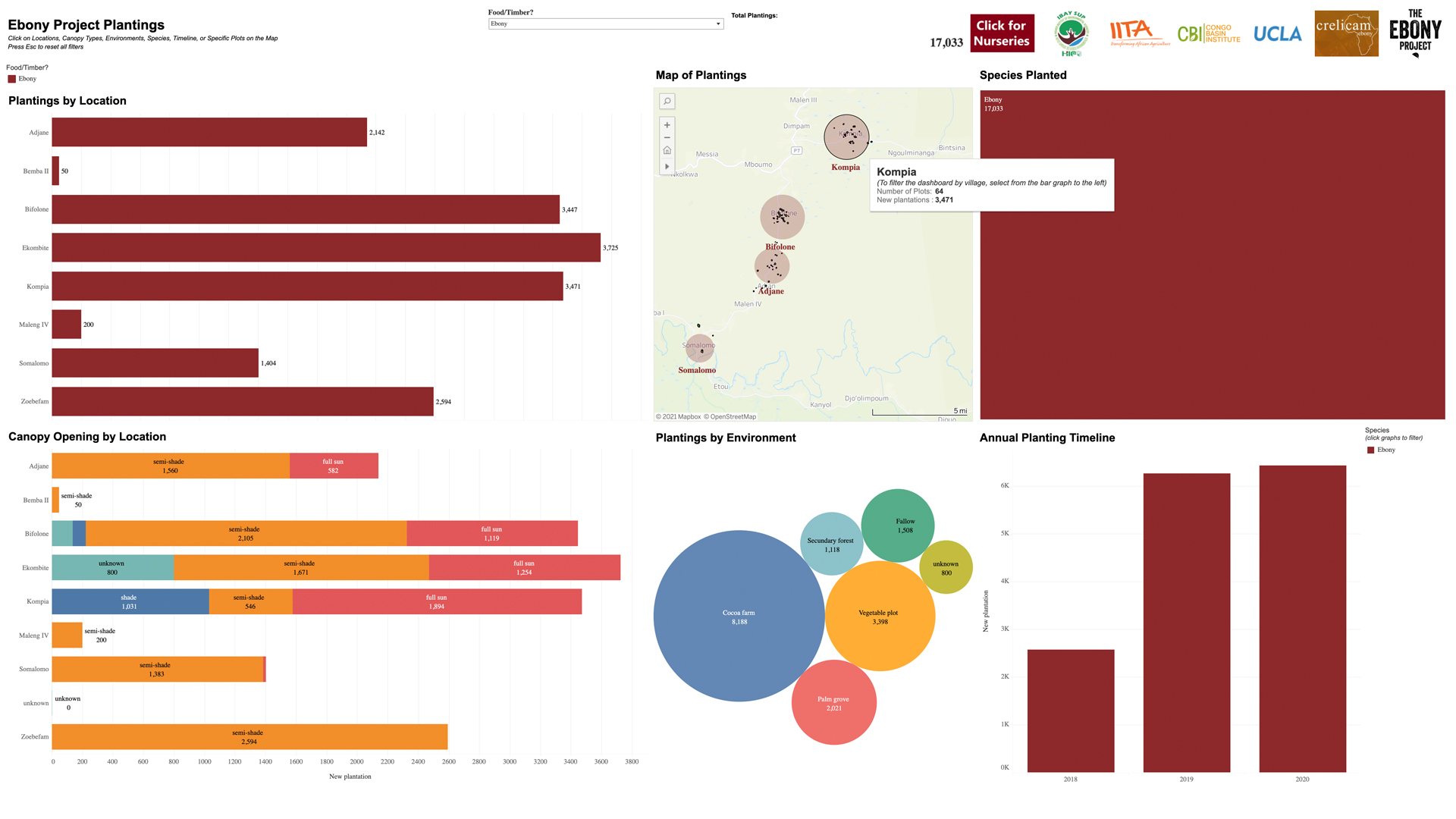

Since the listing of neo-tropical populations of Big Leaf mahogany on Appendix II in 2002, several additional tree species have also been listed, including several tonewoods. In 2017, the entire Dalbergia genus (rosewood) was listed on Appendix II, and in 2022, one of the so-called African mahoganies, khaya (Khaya ivorensis), was listed. Pernambuco (Paubrasilia echinate), used to make bows for stringed instruments such as violins and cellos, was originally listed in 2007 and revised in 2022. It is not clear which commercially traded tree species will be listed next, but it is clear that more will be. Undoubtably some will be tonewood.

Taylor Guitars will stay engaged in the CITES process and will monitor changes in legislation home and abroad. The world is changing, and we have to change too. As I said earlier, we’re organizing, digitizing, tracking and monitoring like never before. And part of that process is to get a little more deliberate, a little more consistent, about what we call the woods we use. So, moving forward, if it’s genuine mahogany of the Swietenia genus, we’re just going to call it mahogany, regardless of whether it grew in its native range in the Americas or if it was long ago planted elsewhere. We’ll continue to call sapele sapele, although when we first introduced it on our 300 Series in 1998, we did for a time call it “African mahogany.” All this said, rest assured, that behind the serial number, we’re tracking everything closely.

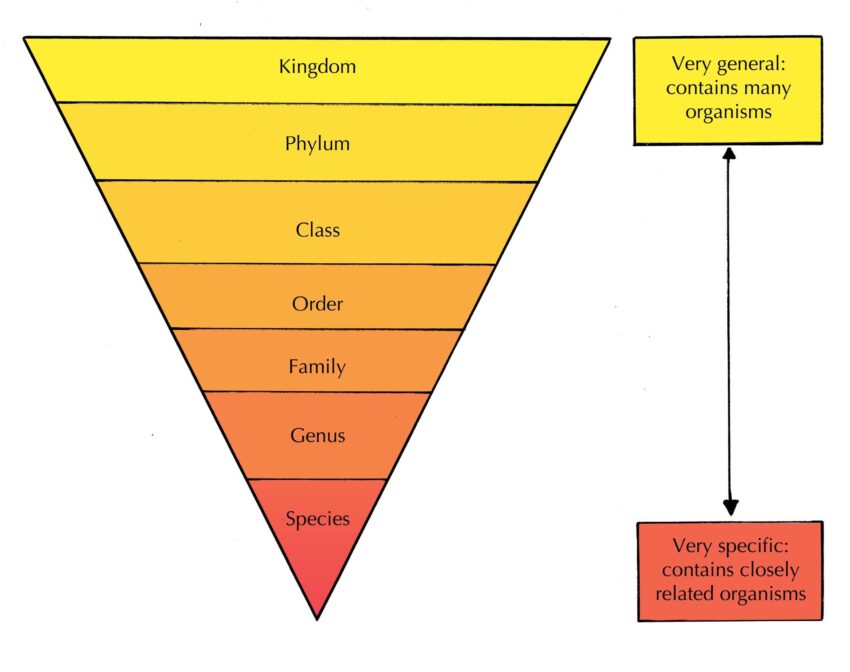

In biology, taxonomy is the study of naming, defining and classifying groups of living organisms. There are eight levels in a hierarchy: species, genus, family, order, class, phylum, kingdom and domain. Species are grouped within genera, genera are grouped within families, etc. Or, think of it this way: Species are the most specific of the levels.

In biology, taxonomy is the study of naming, defining and classifying groups of living organisms. There are eight levels in a hierarchy: species, genus, family, order, class, phylum, kingdom and domain. Species are grouped within genera, genera are grouped within families, etc. Or, think of it this way: Species are the most specific of the levels.