Taylor’s sustainability efforts continue to move forward with active projects focused on ebony in Cameroon, koa in Hawaii, and urban trees here in our home state of California. We thought we’d provide an update on each of these “big three” initiatives, with others also in the works. Each project is remarkably unique, reflecting the complex realities of the respective regions, cultures, ecosystems, and of course the tonewood species involved.

All are connected, however, by our underlying commitment to give back to the people and places where we source while attempting to create a better future for the tonewoods used by our company to build guitars.

One important reason we want to bring a lens to these projects, beyond our desire to operate with transparency, is to demonstrate what is possible and to inspire others. We may be “just” a guitar company, but with innovative thinking, a collaborative mindset, and the willingness to persevere, we believe a lot can be accomplished.

Meanwhile, as we continue to shape our dynamic new digital platform for Wood&Steel, we look forward to providing a more immersive range of content around these three projects, all in an effort to enrich your perspective into this work. In many ways, the Ebony Project website experience we launched back in 2018 set the stage for the type of storytelling we hope to bring you, and over time, we plan to create more of these experiences through this new Wood&Steel format.

Cameroon: The Ebony Project

Ebony’s Journey: From Forest to Fingerboard

Follow the life cycle of an ebony tree, from a plant in a community nursery in Cameroon to the forest, where it will grow big and tall over many decades; to the Crelicam ebony mill in the country’s capital of Yaoundé; to the Taylor factory in El Cajon, California; and ultimately to the hands of a musician as an integral component of a guitar.

If you’re not familiar with what has developed into what we call the Ebony Project, allow me to recap. It all began in 2011, when Taylor and Spanish tonewood supplier Madinter purchased the Crelicam ebony mill in Yaoundé, Cameroon. We did so for several reasons, but, first and foremost, it allowed us to take direct responsibility for our sourcing of ebony, an important tonewood that our industry has traditionally used. (Every Taylor guitar features an ebony fretboard and bridge.) In short, once Crelicam was purchased, the ethical buck stopped with us.

The first few years, admittedly, were tough, but we slowly made much-needed physical improvements to the factory, advanced working conditions, and increased efficiencies. In 2013, our efforts were recognized with the U.S. Secretary of State’s Award for Corporate Excellence, which recognizes a U.S. company that upholds the highest standards of business and adds value to the communities where they do business abroad.

About this same time, we also became interested in planting ebony for the future. We established an ebony nursery at Crelicam, but the initial results were mixed. As Bob Taylor and others tried to research ebony propagation, they learned that there was a surprising lack of information available pertaining to the species itself (Diospyros crassiflora Hiern). Bob commissioned an independent literature review, which confirmed the dearth of basic information about the ecology of ebony, such as how the tree reproduces. The review concluded that the silviculture of African ebony was largely incomplete.

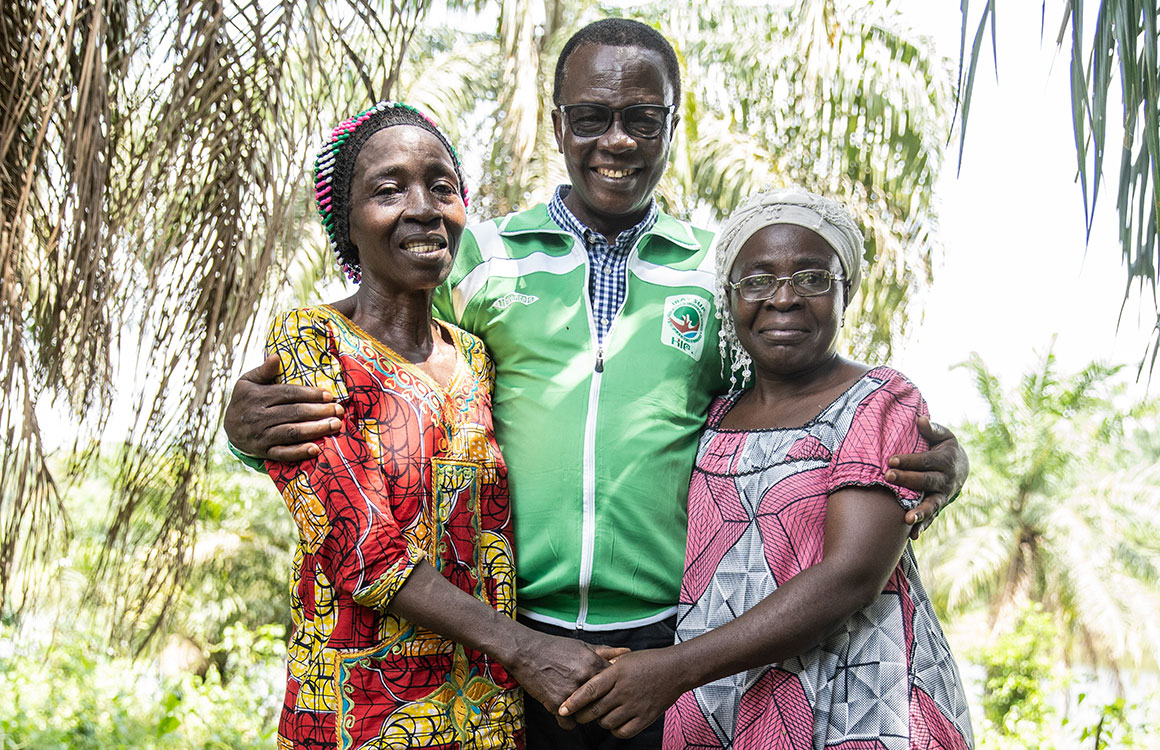

For this reason, in 2016 we launched the Ebony Project in partnership with the Congo Basin Institute (CBI). The plan was to conduct basic research into ebony ecology and to plant 15,000 ebony trees in several small communities that buffer the Dja Forest Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in southeastern Cameroon. Because food security is an important issue in this region, the plantings also include fruit trees to provide a recurring food source for participating communities. Bob and his wife Cindy personally funded the entire project. (For more on these efforts, check out the Ebony Project website along with a few back issues of Wood&Steel, including Vol. 91 / Summer 2018 and Vol. 94 / Summer 2019.

Since then, CBI’s Dr. Vincent Deblauwe and his research team have made several landmark scientific discoveries, including some of the first documentation of the insects that pollinate the ebony flower and the mammals that disperse the seeds, and have had great success producing and planting ebony. This year we will surpass our original goal of planting 15,000 trees. Several thousand fruit trees have been planted too.

In 2019, the conservation forecast for West African ebony was improved on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species — due in part to a greater understanding of the species because of Dr. Deblauwe’s work. That same year, a scale-up feasibility study for the Ebony Project was completed, as called for in the Public-Private Partnership Agreement between Taylor Guitars and the Cameroonian Minister of Environment signed at the United Nations Climate Convention negotiations in Bonn, Germany in 2017. Think of the scale-up study as a roadmap for growing the project beyond what Bob and Cindy can fund alone. This year we welcomed the support of the Franklinia Foundation and the University of California, whose contributions will further support ongoing scientific research and have enabled the project to expand from a planned total of six villages to eight by this year’s end. In 2020, participating villages will plant as many as 9,000 ebony trees and 2,800 fruit trees.

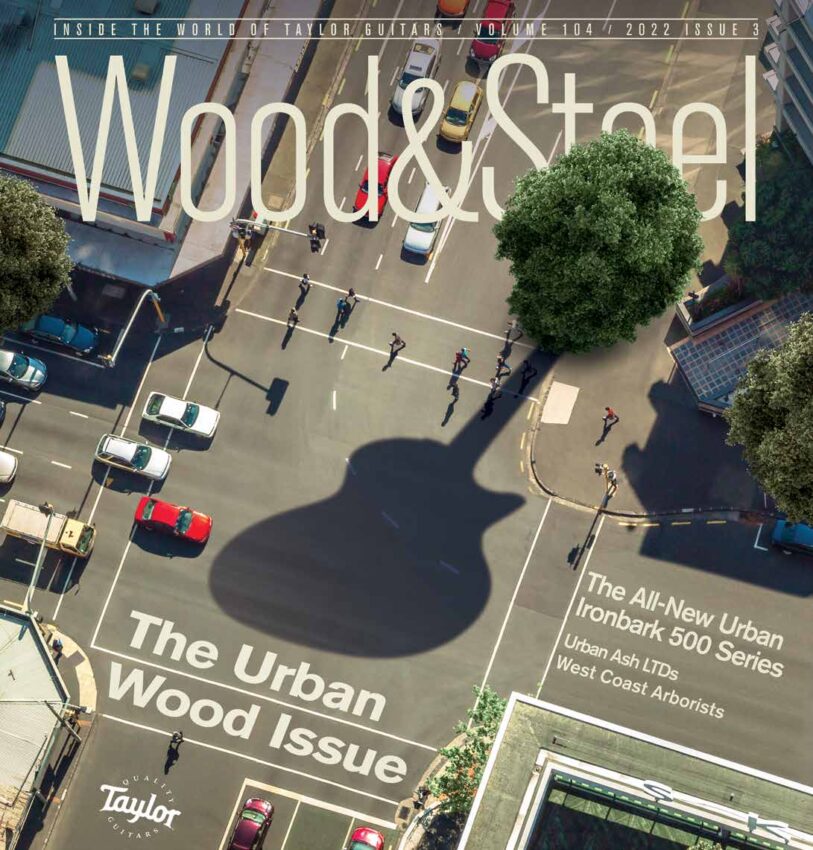

Southern California: Urban Ash

Taylor’s Urban Wood Initiative

Scott Paul explains the vision behind Taylor’s urban wood initiative and our collaboration with West Coast Arborists

At the 2020 Winter NAMM Show held this past January, Taylor unveiled a new guitar, the Builder’s Edition 324ce, and with it also introduced a promising new tonewood to the acoustic guitar world: Urban Ash™, more commonly known as Shamel or Evergreen Ash (Fraxinus udhei). What we call Urban Ash is native to the semi-arid regions of Mexico and parts of Central America but was brought to California by Archie Shamel in the early 1950s. Shamel worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and thought the ash species desirable as a fast-growing shade tree amid Southern California’s post-war home construction boom. The species was propagated by local nurseries and planted across the region, and today is common from Northern to Southern California. While still planted today, some older trees are reaching the end of their lifespan and are being removed.

The Challenges of Maintaining an Urban Forest

On public land, the city or town decides what to plant, when to plant, and whether to care for or remove a tree. Unfortunately, tree planting, maintenance and removal are typically grossly underfunded line items on any given city’s budget, often competing with other vital public services like police and fire departments for scarce resources. As a result, in the United States, the average life span for an urban tree is only eight years. Trees are often neglected (not adequately watered) and sometimes uprooted by an everchanging urban environment. This said, many trees do survive, grow, thrive and become large in time.

There are many legitimate reasons why a city tree must eventually be removed, such as old age, public safety if the tree is weakened by disease, invasive pests or storms, and in some cases to make room for development. This gives rise to social tension. Simply put, we all want to plant more trees — after all, trees are a good thing — but existing city trees have a finite life in spite of the multiple benefits that they provide. When a city does decide to take down a tree, many citizens understandably get upset and, on occasion, may seek to save a tree without fully understanding the need for renewal. To further complicate matters, historically there hasn’t been a high-value market for the wood from these removed trees, and the cost of disposing city trees is becoming increasingly expensive.

A Second Life for Urban Trees

With the release of the Builder’s Edition 324ce, Taylor has opened up a new sustainability initiative that is exploring ways to turn end-of-life urban trees into high-value products that can hopefully support the regreening of our urban infrastructure and, perhaps, in time, ease the pressure on forests elsewhere. In doing so, we are aware of both the decline in urban tree cover worldwide and the fact that arborists and city officials are struggling with escalating disposal costs and the political turmoil that can accompany urban tree removal.

As we do with everything, Taylor Guitars will attempt to use business to drive positive change. As I described in my Wood&Steel column, “Seeing the Urban Forest for the Trees” (Vol 96 / 2020 edition, page 8), figuring out a circular economy that creates jobs and supports the planting, maintenance, disposal and repurposing of urban trees is going to be increasingly important. Our goal is to see that the maximum benefits of trees are considered for all of society to enjoy, such as air and water quality, energy savings, and mental and spiritual well-being. We obviously can’t do this alone, and this is why we’re partnering with our local arborist here in El Cajon — West Coast Arborists, Inc., a well-established municipal tree maintenance company that works across the entire state of California. Together, we can attempt to lead by example. In time, we hope to expand our efforts everywhere our brand can reach. Soon I hope to update you on several urban tree planting initiatives that Taylor and WCA will be involved with.

To learn more about the Builder’s Edition 324ce and our new partnership with West Coast Arborists, please see Wood&Steel Vol 96 2020 Issue.

Hear the Builder’s Edition 324ce

Taylor’s Andy Powers plays a Builder’s Edition 324ce featuring Urban Ash back and sides.

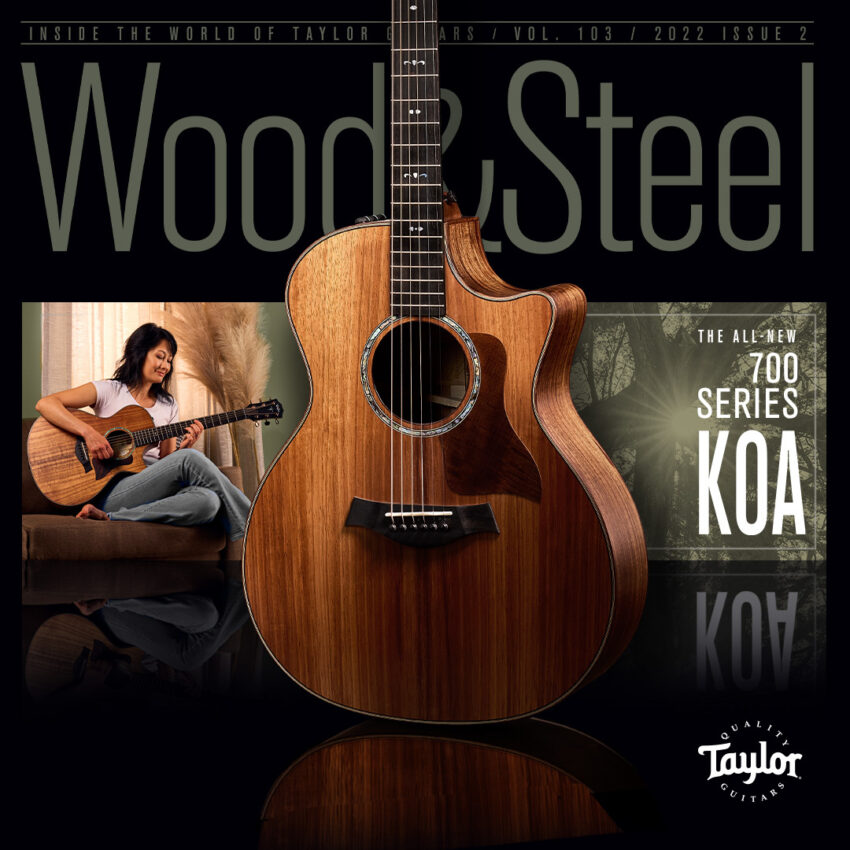

Hawaii: Native Forest Restoration

Many Wood&Steel readers will recognize the name Paniolo Tonewoods. A joint venture between tonewood sawmill/supplier Pacific Rim Tonewoods and Taylor Guitars, the company was established in 2015 with the goal of cutting koa trees to make guitars while simultaneously contributing to the long-term vitality of native Hawaiian forests. I realize it may sound counterintuitive to cut trees in the name of forest recovery, but due in part to the nature of island ecology, and Hawaiian koa in particular, Paniolo will improve the quality of the Hawaiian forests where it operates over time. Let me explain how.

Island ecosystems such as Hawaii’s are especially vulnerable to invasive species. After all, Hawaii is among the most isolated archipelagos in the world, resulting in unique plant and animal species, which developed in this isolation and are thus ill-suited to competition and disruption. A majority of forest ecosystems in Hawaii have been in a state of slow decline due to invasive weed species, fire and predation by introduced grazing animals such as sheep and cattle. Kahili ginger, for example, forms in vast, dense colonies that choke understory vegetation, earning it the dubious distinction of being included on the Invasive Species Specialist Group list of 100 most invasive species in the world. Such invasive “transformer” plant species have the capacity to modify or displace entire ecosystems. Various grass species, which have evolved with fire, have been introduced in Hawaii to improve grazing quality. They also provide the fine fuels to carry devastating fires into native forests, which are not at all fire-adapted. Exacerbating all this, understory grazing by non-native deer, feral sheep and cattle lead to the chewing, stomping and destruction of young trees, which lack defenses. Naturally germinating young koa is like an all-you-can-eat salad bar for these roaming ruminants. This is why fencing, weed management and fire breaks are all so important. The Hawaiian native forest areas where Paniolo Tonewoods operates need proper management to recover. And proper forest management is not cheap.

Paniolo Tonewoods was created to ensure a future supply for koa tonewood by regenerating koa within native forests, installing fencing, providing fire protection, and removing invasive weeds. This is complemented with the natural germination of koa seeds that remain buried in the soil or by the planting of thousands of koa seedlings grown in nurseries. Despite these lofty goals, during its first two years, Paniolo obtained koa the same way we always have, by purchasing select logs from private lands as they became available. This changed in in 2016, when Paniolo began working with a private ranch on Maui.

This ranch had 20-plus acres of 30-year-old planted koa trees in two groves that had started to decline and show signs of rot. (Koa wood is very susceptible to rot, and the ranch managers knew that these trees would only get worse.) These unique groves had originally been established on a remote part of the property, and unfortunately, wild deer found their way through the fence and began eating the young koa saplings, stunting and disfiguring their growth. Conventional wisdom in 2016 suggested that 30-year old koa under the best of circumstances was of no real economic value. Nonetheless, Paniolo worked with Taylor to address quality standards and found the guitar wood in these trees. Proceeds of this sale allowed the ranch to build additional new deer-proof fencing and to expand their ongoing koa planting and maintenance efforts on their property. They continue to plant koa on their property at a rate of 10-15 acres per year.

Honaunau

The next project for Paniolo Tonewoods was Honaunau, on forestland owned by the largest private landowner in Hawaii. Here again, Paniolo Tonewoods used an innovative approach pioneered by the U.S. Forest Service. Instead of paying for logs or harvesting rights directly to the landowner, which is the norm, Paniolo was allowed to cut a select number of designated trees, and in exchange, was responsible to pay dollar for dollar for a host of forest improvement projects. These include new fences to keep damaging feral sheep and cattle out, improved fire breaks, and environmental and archeological studies. To date, this has resulted in the re-investment of over $500,000 into the koa forests of Honaunau. This project also continues and is projected to re-invest an additional $500,000 in the next few years — all of this on land that the landowner did not otherwise plan to regenerate and protect. Thus, another 1,600 acres of Hawaiian native forest is being improved and protected.

Paniolo’s Future Koa Forest

On March 9, 2018, Bob Taylor purchased 564 acres of rolling pastureland on the north end of Hawaii Island. This land is now managed by Paniolo Tonewoods, who will, over time, re-create a native Hawaiian forest on lands that had been cleared for pasture use for at least 100 years. The plan is for Paniolo to plant the steep-sloped areas in mixed-species native forest and to plant the more gently sloped areas with koa for timber production. Apart from a simple road network and small mill site, when the forest is mature (beginning roughly 30 years after planting and continuing in perpetuity), it will remain in relative closed canopy and is projected to produce more than twice the volume of koa wood that Taylor Guitars uses today via selective cutting of trees.

It is important to understand that as of today, Paniolo itself has only planted a few trees. Our work to date has enabled others to do so and has protected 1,600 acres of native forest in Honaunau (not an insignificant achievement), but, having been around for a mere four years, Paniolo is only starting. In 2020, we will start planting out Bob’s property, but to do it right takes time. As we go, Paniolo will continue its research into growing trees with superior quality and hopefully add to growing seed and plant improvement efforts statewide.

Scott Paul is Taylor’s Director of Natural Resource Sustainability.